India: Music’s new ambassadors

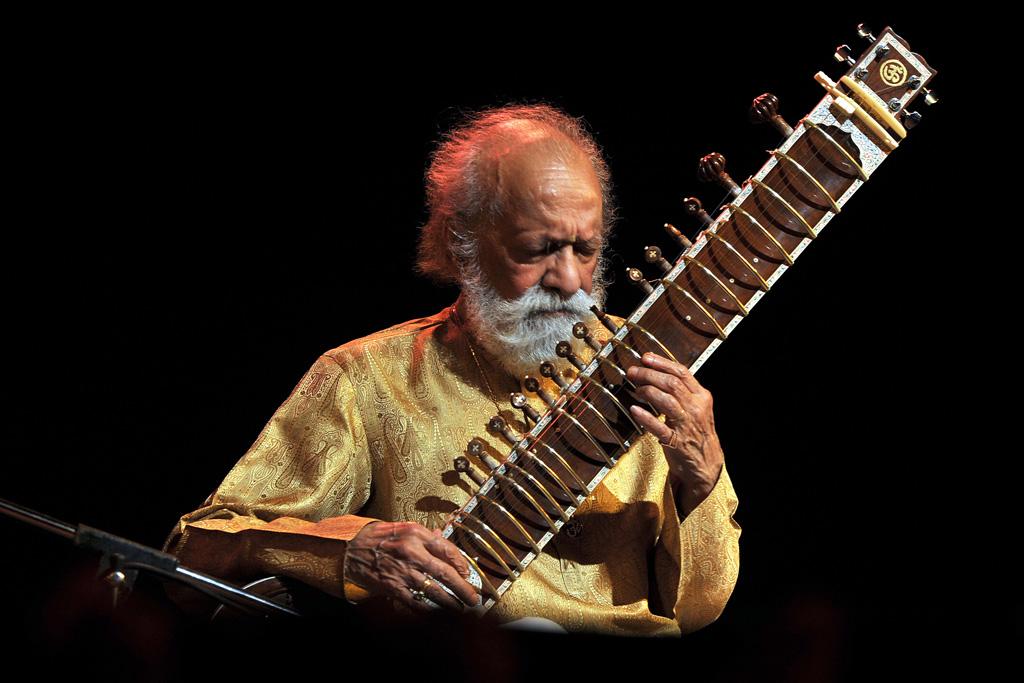

Ravi Shankar plays his sitar at the Palace Grounds in Bangalore, India, Feb. 7, 2012.

NEW DELHI, India — When sitar master Ravi Shankar finally succumbed to time last week, Indian music lost its first and most famous ambassador. But a healthy crop of musicians are carrying the torch — straddling pop, indie, Bollywood and classical genres. Here are some names to follow.

Classical music

Zakir Hussain — a former child prodigy who first toured the US in 1970 — has done for the tabla what Shankar did for the sitar. In 1992 and 2009, he collaborated with Mickey Hart, Sikiru Adepoju, and Giovanni Hidalgo on the Grammy-winning “Planet Drum” and “Global Drum Project” albums to introduce the world to Indian classical's curiously melodious drum. In earlier years, Hussain played with John McLaughlin's Shakti — one of the first efforts to fuse the rhythms and melodies of classical Indian ragas with the improvisations of western jazz — touring extensively in the late 1970s. He worked on the soundtracks of Francis Ford Coppola's “Apocalypse Now” and Bernardo Bertolucci's “Little Buddha.” And he's capitalized on the growing crossover audience for Indian films, and films made by the Indian diaspora, with acting cameos and soundtrack work for movies such as Aparna Sen's “Mr. and Mrs. Iyer” and Ismail Merchant's “The Mystic Masseur.”

“Aside from the fact that [Hussain] works magic on the tabla, I think it's his ability to align himself to various styles, various vocabularies of music [that has made him an important ambassador for Indian music],” said Chennai-based cultural critic Nandini Krishnan.

Other heirs to Shankar's legacy include slide guitarist Debashish Bhattacharya, whose “Calcutta Chronicles” was nominated for a Grammy in 2009; classical pianist Anil Srinivasan; and Uppalapu “Mandolin” Srinivas, who plays the mandolin (natch). In addition to “Calcutta Chronicles,” Bhattacharya won over Western fans with “Calcutta Slide-Guitar, Vol. 3.” (2005) and “Mahima” (2003) in collaboration with American guitarist Bob Brozman — both of which made Billboard's World Music Top Ten. Srinivas, who dueled with Miles Davis at the West Berlin Jazz Festival in 1983, has in recent years brought South India's Carnatic music to the global audience by collaborating with McLaughlin's Shakti and artists as wide-ranging as King Crimson's Trey Gunn and Chinese yangqin master Liu Yuening. And Srinivasan has brought his unique merger of classical piano and South Indian Carnatic music to audiences at New York's Lincoln Center, the Sydney Opera House and the National Center for the Traditional Performing Arts in Korea.

In other words, Shankar may be gone, but his legacy is bigger than ever.

“Most of us now are getting an opportunity to perform at mainstream venues as part of festivals,” said Srinivasan. “To a large extent this is something that Uday Shankar and Ravi Shankar created for Indian music.”

“[Second], you have Indian music inveigling itself into many different global music forms, starting with AR Rahman and going all the way down to myriad composers and choreographers and other people,” Srinivasan said.

“Rather than one person or group of people who are ambassadors, you have a lot of different influences and influencers. It's a certain philosophy towards composition that has changed worldwide.”

Bollywood

That brings us to Bollywood, where Grammy-winner A.R. Rahman and music directors like Amit Trivedi have introduced sounds from Indian folk and classical music into love songs and dance tracks and taken advantage of Indian film's growing global popularity to gain a wider audience.

“A music director like Amit Trivedi is different from the genius music directors from the '50s, who created a gorgeous sound but also brought in many of the nuances of Indian classical and light classical music, as it's called in India, into their compositions,” said novelist (and classical Hindustani vocalist) Amit Chaudhuri — whose own “This Is Not Fusion” project has created a minor internet sensation since he began it in 2003.

Trivedi's pathbreaking soundtrack to 2010's “Dev. D” in some ways redefined what Bollywood music could be — albeit in one of a new crop of independent films. Songs like "Emosanal Attyachar,” for instance, blend the raucous music of the brass bands that play Indian weddings with western-style rock influences and wordplay worthy of Bob Dylan.

“The singer used to be central for those older music director,” Chaudhuri said. “Now it seems the singer is just one element in a soundscape that these directors are creating.”

Beyond the Grammy-winning soundtrack to “Slumdog Millionaire” and “Jai Ho,” Rahman has won crossover fans with some of modern Bollywood's most memorable songs (think “Chaiya Chaiya”):

He's also collaborated with artists ranging from Michael Jackson to Andrew Lloyd Webber and Vanessa Mae — making him the top-of-mind choice for Indian music's new ambassador.

“What Rahman is basing his music on is a few [elements] picked up from Indian folk music, a few picked up from classical and a few picked up from Western music,” said Delhi University music professor Deepti Bhalla. “You cannot say it has a classical base or a folk base. It is a mix of everything.”

Still, not everybody is convinced that Bollywood's role as ambassador of Indian music is a good thing.

“The biggest influence on the West, or what the West understands as Indian music, is the sound of Bollywood,” said Krishnan.

“This amuses me, because several Bollywood composers have stolen popular Western tracks. Try 'Dil Mera Churaya Kyon' from Akele Hum Akele Tum and George Michael's 'Last Christmas', or 'Haseena Gori Gori' and Shaggy's 'In the Summertime.'”

Pop, indie and “new” fusion

The post-Shankar era is also bristling with Indian and Indian-origin pop, indie and fusion artists, who transcend borders and boundaries in ways that the sitar master couldn't have dreamed possible when he was teaching George Harrison to play.

In India, artists like singer-songwriter Raghu Dixit of the Raghu Dixit Project are starting to gain an international audience for Indian “indie” music:

while non-Bollywood popstars like Daler Mehndi have caught the ear of international artists such as the UK's Rajinder Singh Rai (aka Panjabi MC) and Jay-Z — making so-called “bhangra nights” a fixture at clubs in London, New York and beyond.

In the UK, indie artists like Talvin Singh and Nitin Sawhney have in recent years popularized a sub-genre of electronica known as “Asian Underground” that incorporates Indian instruments and melodies, while Cornershop's Tjinder and Avtar Singh brought Indian instruments and sampling to Britpop in songs like “Brimful of Asha.”

And the late-blooming US diaspora is now getting into the game, with Brooklyn-based Himanshu Suri and Ashok Kondabolu of Das Racist bringing an Indian vibe to hip hop and Brooklyn-based Rudresh Mahan Thapar and Vijay Iyer combining Indian sounds with Western jazz.

“[The UK's] Arun Ghosh, Vijay Iyer, and Rudresh Mahan Thapar all started out as western-style jazz players and they began to explore their cultural origins,” said Chaudhuri, who counts his own “This Is Not Fusion” as part of the same musical movement.

“It's a move away from the kind of Shakti-idea of fusion, where you had western harmonies and Indian instruments and raga and you brought the two together,” Chaudhuri explained. “This new music was done by people who were not looking at either Western or Eastern music from the outside.”

In other words: Maybe Indian music doesn't really need “ambassadors” any more.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?