British food: how the cuisine world’s butt of jokes went from bland to sexy

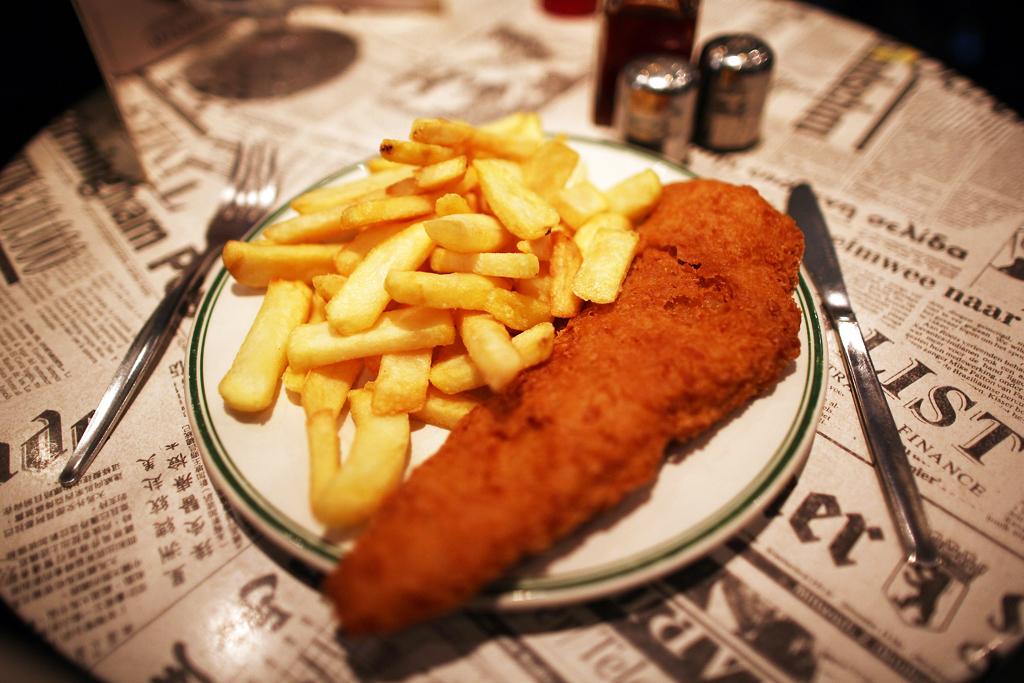

A traditional dish of Fish and Chips is placed on a table in a cafe on February 22, 2011 in London, England.

SHEFFIELD, England – For many Brits who grew up in the 1970s, restaurant meals entailed a choice between steak and chips (fries), or something called scampi-in-the-basket — deep-fried seafood of uncertain origin served exotically in a wicker basket lined with fat-absorbing paper.

Things have changed.

In Britain and across much of northern Europe, the past few years have ushered in a culinary revolution.

In the San Pellegrino world's best restaurant awards announced last month, Britain had three in the top 15, one more than France. Denmark's Noma claimed top spot for the third year running, while Sweden tied with Italy with three top 50 places. Last year chefs from Denmark, Sweden and Norway took the top three places in the Bocuse d'Or contest, commonly viewed as the culinary Olympics.

France's Michelin Guide awarded a record 176 of its coveted stars to British and Irish restaurants in 2012. That compares to just 25 when the first edition was released in 1974.

"If you go back 30 years, it was deep fried this, deep fired that, very bland food," recalls Justin Rowntree, joint-owner of the award-winning Silversmiths restaurant in this northern English city.

"I remember when my father first brought home some garlic, back in the mid-70s, it was: wow what is this strange thing?"

More than GlobalPost: Korean food's popularity soars

Recently picked by The Times newspaper as one of the five sexiest places to eat in Britain, Silversmiths is typical of the food renaissance that has swept northern European countries from Iceland to Estonia.

The food is sourced from local farms. The May menu included delights such as: peppered mackerel “cheesecake” with English asparagus; twice cooked smoked pork belly, stuffed pigs head, Yorkshire sausage patty, sage mash, watercress and bacon crisp; and strawberry tea infused mini raisin scones, home-made saffron clotted cream and Yorkshire lemon curd.

Cooking of this quality used to be reserved for the wealthy few, but as food has become a national obsession, good, affordable restaurants have proliferated. Britain now has more restaurants than any other European Union nation and accounts for a quarter of all EU spending on restaurants and bars.

Traditional pubs — where snacks used to be limited to delights like pickled eggs or prawn-cocktail flavored potato chips — have been transformed into innovative gastro-pubs. A pint at The Ginger Dog in Brighton, for example, can be accompanied with smoked eel and confit pork terrine or steamed skate wing with crushed new potatoes, roast baby fennel and sauce vierge.

It's a far cry from the days when British food was the butt of foreigners' jokes.

"One cannot trust people whose cuisine is so bad," French President Jacques Chirac, was overheard chuckling with his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin in 2005. "The only thing they have ever done for European agriculture is mad cow disease."

More from GlobalPost: What feta and reindeer meat have in common

Britain's food revival can be put down to immigration, tourism and television.

The spread of Indian restaurants serving affordable, high-quality and highly spiced food invigorated British palates. Low cost flights to continental Europe added to their appetite for better food. TV picked up on the trends, with emergence of celebrity chefs like Gordon Ramsay and Jamie Oliver who made food sexy and helped turn the British into a nation of foodies.

"In 10 years we've moved from being a culinary backwater to a nation obsessed with food in all its forms," food writer Tim Hayward, mused recently in The Observer, a Sunday newspaper. "It's a time of fertile flowering and we are finally catching up with the rest of our European neighbors."

Broadly speaking, those neighbors include nations south of an arc drawn from Belgium to Greece, where robust gastronomic traditions survived the post-war lurch to mass-produced convenience foods. In much of northern and eastern Europe, food suffered the same fate as the Britain, but is now enjoying a similar revival.

The philosophy at Copenhagen's Noma, which superstar chef Rene Redzepi has turned into the high-temple of modern cooking, sums up the thinking of many of northern Europe's new wave of locally rooted restaurants.

"We regard it as a personal challenge to help bring about a revival of Nordic cuisine and let its distinctive flavors and particular regional character brighten up the world," says the restaurant's web site.

"Noma is not about olive oil, foie gras, sun-dried tomatoes and black olives. On the contrary, we’ve been busy exploring the Nordic regions discovering outstanding foods and bringing them back to Denmark: Icelandic skyr curd, halibut, Greenland musk ox, berries and water."

A generation of chefs are now applying that approach, modernizing half-forgotten recipes and digging up long-out-of-favor products.

t'Arsenaal, a restaurant beneath the walls of a 16th-century church in the Dutch city of Deventer serves North Sea sole and shrimp with lovage leaves; the Thornstroms Kok restaurant in Goteborg, Sweden, has a dish combining local asparagus with nettle forth, water cress and the roe of a freshwater fish called bleak; Estonian chef Peeter Pihel makes ice-cream from Christmas tree needles.

More from GlobalPost: Germany battles over future of solar

"You can also salt them, or make a great syrup from them," says Pihel, who cooks in the award-winning Padeste Manor hotel on the Baltic Sea island of Muhu. "Local food, small farmers, that's what's coming back again. It's very popular now."

Back in Sheffield, Rowntree recalls how he got the go-local message after a roasting from Gordon Ramsay on the Kitchen Nightmares show. That made him ditch his Spanish tapas bar and reopen as modern British restaurant with its focus on food produced in the surrounding county of Yorkshire.

"Over the last five or 10 years the idea of local food provenance, of using local supplies, taking food from our own backyard and back garden, literally, has really taken off," he said in an interview. "Whether people are cooking Italian food, French food, or British food like I do, keeping it local, keeping the money in the local economy has become something that people are really focused on."

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!