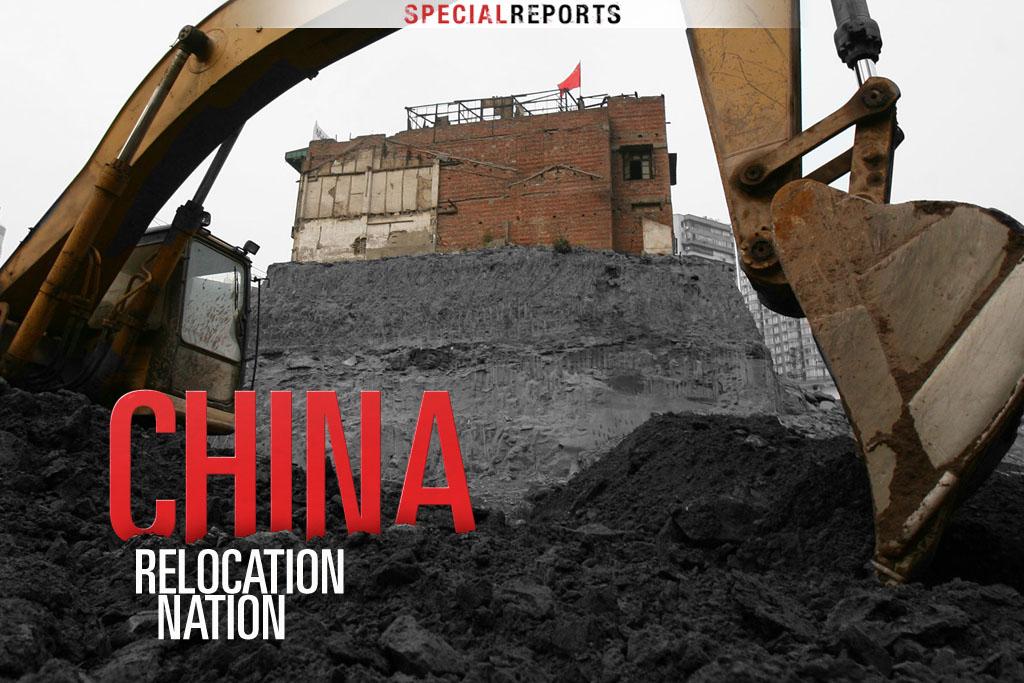

China’s biggest relocation project yet

Illustration by Antler.

ANKANG, China — A decade from now, the quiet mountains and farm villages across this vast ribbon of central China will be modern towns and cities.

Farmers will be urbanites, and the region’s main river will be cleaned up and channeled toward Beijing. That is, if all goes according to plan.

There are many variables standing in the way — namely people, and China’s largest-ever forced relocation project.

In order to transform this stretch of the Qinling mountains prone to earthquakes and landslides to a safe urban zone, and to channel the river north, the Shaanxi provincial government will move more than 2.5 million people off the rivers and mountains. In the north of the province, another half-a-million people are slated for relocation.

That 3 million is twice the number of people resettled to make way for the world’s largest dam, at the Three Gorges of the Yangtze River.

Shaanxi’s relocation plan, tied in part to China’s massive South-North Water Diversion Project, will change the geographic heart of the country. The Han River, which runs through these mountains, is a key tributary of the Yangtze. It's one of three channels being diverted to deliver trillion of gallons of water per year north.

People problems

Only a few months in on the relocation scheme, serious problems are emerging.

In the village of Qiyan, nestled along the Han River, row-upon-row of new and tidy white farmhouses are taking shape, replacing crumbling homes that have fallen to deadly mudslides and earthquakes.

This is the exception. New Qiyan, which supplanted the town where landslides killed several villagers last year, is known in these parts as “the model village,” a showpiece.

A stone’s throw away, in the 2,000-person village of Pingchuan, it’s a different story. Townspeople say promises of better living and fair compensation are unfulfilled and all they’ve got is a mountain of debt, no land and a bad apartment building.

As the model villagers of Qiyan get new, bright farmhouses, the residents of Pingchuan will be packed into six-floor walk-ups. In both villages, farmers are saddled with bank loans of at least $8,000 per family. This in a place where a strong worker can cobble together about $450 a month income from factory and farm labor.

“It will take everyone at least five or 10 years to repay the money,” said Yang Yuantao, Pingchuan’s mayor. “They weren’t rich to begin with, they all have unstable incomes and this is only going to make things worse.”

Pingchuan’s residents have a reputation for complaining. This, they believe, is why they’ve been slated for a high-rise rather than new farmhouses and still lack the road, toilets and community center promised for the new village.

Mayor Yang, speaking from the sofa in the new living room of one villager in the apartments, smiles faintly when asked about the future of his mountain village.

“We’re just trying to get by; it’s never easy,” he said. “It’s a bitter fate.”

Problems abound

Pingchuan’s complaints are the tip of the iceberg. Across hundreds of miles in the mountains and valleys of southern Shaanxi, residents expressed fear, anger and uncertainty about the ambitious relocation plan.

Government officials declined to be interviewed and the official relocation plan barely mentions the South-North Water Diversion project, but it’s clear from plentiful mountainside propaganda posters along the route that cleaning up the river is helping drive relocation.

Mile after mile on mountain roads, thousands of workers are installing new water treatment plants and rechanneling the river with giant earthmovers. Mountainside banners urge farmers to “send clean water to Beijing.”

For that reason, they’re being moved off of their own farmland, pushed toward organic farm practices and encouraged to take jobs in the emergent construction industry. Near Qiyan, villagers hope a bottled-water factory will employ many of those who lose their farms.

Area bigger than France

The scale of the project is massive, the bulk of it reaching across the three southernmost municipalities of Shaanxi, a geographic area larger than France. That’s not counting the resettlement areas in the north.

Already, this remote region with no working airport is being transformed by new infrastructure, including a high-speed rail and modern four-lane highways. New tunnels and bridges are blasted across the landscape as farmers learn about plans to uproot their lives.

“It’s difficult because farmland is disappearing and people have to go out to look for work now,” said Dong Mingfeng, vice mayor in a relocated village where the residents are happy with their new homes.

“They work now on these projects like building tunnels,” she said. “They get [$400-500] a month and when they come home, they’re so dirty their own families don’t recognize them. Many people have died because it’s such dangerous work.”

Shaanxi officials tell state-run media that relocation will make people’s lives better, and richer.

"This relocation project is for the benefit of the people," Shaanxi Governor Zhao Zhengyong told the Xinhua news agency. "It aims to give people a safer and more convenient environment in which to live their lives."

Deep in debt

But so far, in many places, the plan has only put farmers in debt to banks for the first time in their lives.

According to the plan, the government will pay farmers compensation that covers 10-15 percent of the cost of their new home, then provides low- or no-interest loans for the rest. In the beginning, many villagers say they were promised interest-free loans on the homes now under construction. But farmers with new mortgages are already paying only the interest on their loans.

To be sure, safety is an issue. Pingchuan, for example, is perched precariously on the side of an unstable mountain. Aftershocks from the 2008 earthquake in nearby Sichuan province, and massive earth moving from a nearby coal mine shake the soil, trees and boulders loose at a moment’s notice.

During heavy rains this spring, one woman’s home fell into the river below. Pieces of her ruined furniture still float in the murky water. She has no new home, but is staying with relatives across the road.

Next door, Wei Guojun, 24, and his parents, are waiting and hoping they won’t have to move. They spent their savings a few years ago to build a new house and can’t imagine taking out a loan to buy another one, only to watch their new house demolished.

“We still haven’t gotten an answer yet, but we’ve explained the situation to the government and we hope they let us stay here,” said Wei. “We can’t afford to buy another house.”

The official price tag of the Shaanxi relocation project is nearly $18 billion, but it’s unclear how much of that includes the mortgages farmers are being pushed into.

Boosting GDP

Those in the relocation zone say the move is funded most by those who can least afford it: poor farmers.

Their taking out untold numbers of new bank loans will quickly boost the cash flow in local townships, creating economic development and high GDP increases on paper.

The final fate for nearly everyone in this region seems uncertain. Many don’t know if they must move, while those who do know fear monthly bank payments and losing their farms, when they already own houses and land.

“The rich people are getting richer, the poor are worse off and the difference between us is growing,” said Pingchuan Mayor Yang.