The US and Iran part II – the Shah and the revolution

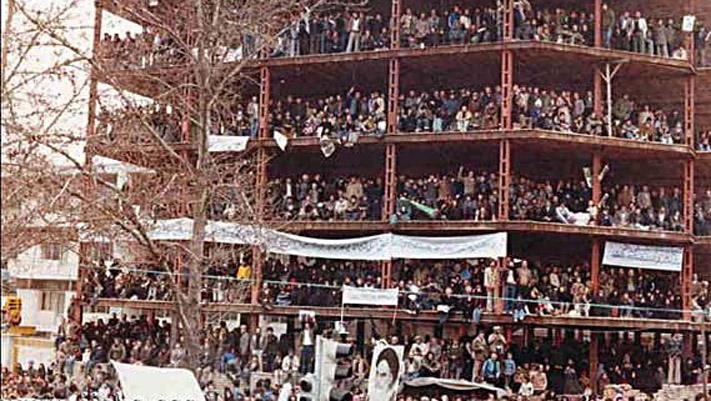

Protestors during Iran’s 1979 revolution.

After the 1953 coup, the United States lost no time in shoring up the Shah's regime. Washington poured money into Iran for economic recovery. It began providing military aid. The United States took one other fateful step: it sent CIA experts to Iran to train a new intelligence agency. That agency grew into the Shah's notorious secret police force, SAVAK.

Nasser Hadian, a political scientist at Tehran University, grew up in the shadow of SAVAK.

"The presence of SAVAK as a very fearful force was almost everywhere and everyone believed that ok, any dissent, any opposition, legal or otherwise would not be tolerated by SAVAK and the people would be arrested and would be tortured. That was the general perception," Hadian says.

Iranians knew the United States lay behind the Shah's new grip on power. And the Shah knew the image of him as America's puppet made him vulnerable. So he set out to reform and strengthen Iran, and to reduce his dependence on the United States.

He had considerable success according to Iranian historian Shaul Bakhash.

"The Shah you know managed Iran's foreign policy extremely well. And certainly between 1963 and 1973 Iran enjoyed a decade of impressive economic growth. But the Shah grew increasingly autocratic. He certainly grew increasingly out of touch with public opinion. And I think he determined that he knew what was best for the country and there was no reason to listen to anybody else," Bakhash says.

The United States kept a close watch on Iran through the 1950s and early 60s. But eventually Washington began to turn its attention to other, more pressing problems. Especially Vietnam. But the United States still needed an ally in the Persian Gulf. In 1972 President Nixon visited the Shah to ask a favor. He wanted the Shah to guarantee US security interests in the region. In return, Washington would allow Iran to buy any weapon system it wanted.

The Shah agreed.

The job of overseeing those arms sales fell to a young foreign service officer in Tehran named Henry Precht.

"They promised the Shah that he could buy whatever he wanted and no one would quibble with him. Everything up to but not including nuclear weapons. So that was my marching orders, facilitate, don't get in the way of this process," Precht says.

Then came the 1973 Arab Israeli war. Oil prices rose dramatically. Suddenly the Shah was flush with oil money. He bought massive quantities of the most high-tech weaponry money could buy. US officials were unsettled by the consequences of their bargain. But Washington had no alternative plan for policing the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

It became taboo to question the arrangement according to Gary Sick, a member of the National Security Council staff under President Carter.

"People in the bureaucracy learned very quickly that anybody who was raising questions about our relationship with the Shah was not really welcome and so people if they didn't like this policy they would find themselves working somewhere else," Sick says.

In deference to the Shah, the United States took another fateful step. Gary Sick says Washington backed off its intelligence gathering inside Iran.

"In the past we'd had a tremendous capacity to read Iran's domestic politics. We basically gave that up so that we were no longer looking at Iran's internal problems. This had huge implications which affected everything that we did from that point on," he says.

What US officials missed as a result of that intelligence gap was an enormous groundswell of resentment against the Shah and the United States. Part of the reason the Americans failed to notice the popular uprising was that it sprang from the mosques.

Bakhash says that by the late 1970s, that was the only place left in Iran to organize dissent.

"Political parties didn't exist, the press was cowed, parliament had become a rubber stamp, there were no civic associations, the government even interfered in the election of presidents and officers of thechamber of commerce for example. So really the only places left for the articulation of political grievances were the mosques," he says.

Islam was an attractive vehicle for Iranian political protest because it had nothing to do with the West. Nasser Hadian says Iranians wanted change, but they wanted that change to be homegrown.

"Everybody was looking for a change which seems to us very authentic, very much belonging to ourselves. Islam and Islamic ideology provided that authenticity for us. All the personalities, all the mythologies, the language, the discourse they were very much familiar even for the ordinary Iranian," Hadian says.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was key to this religious opposition. In the early 1960s he protested the Shah's policies, and the Shah's strong ties to the United States. Clashes between Khomeini's followers and government troops resulted in a bloodbath. The Shah sent him into exile. Khomeini set up shop in next door Iraq. His sermons were smuggled back to Iran on cassette tapes.

His popularity soared, but Sick says the United States didn't take the religious opposition seriously at the time..

"Now we know that was not very smart. That in fact religion was starting to have a very important role. But it was really the Iranian revolution that taught us that. That's where we learned about Islamism, that's where we learned about Islamic fundamentalism, that's where we learned about all these things that we didn't know about but our intelligence at that time was certainly not equipped to look there. And so we missed that completely. It was as if it was invisible," he says.

On New Year's Eve 1977, President Carter visited Tehran.

In retrospect his remarks there show how out of touch he was with popular opinion inside Iran. He lavished praise on the Shah saying:

"Iran, because of the great leadership of the Shah, is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world. This is a great tribute to you, your Majesty, and to your leadership, and to the respect and the admiration and love which your people give to you."

Iran was anything but an "island of stability."

Within days of Carter's visit, the first of the demonstrations that would culminate in the revolution had begun. A popular movement emerged, with Khomeini at its head. But it was not just Islamists. The protests had widespread appeal. The oil boom was highlighting economic disparities. A newly educated middle class was demanding more say in running the country. And the Shah's repression and excesses were alienating even the elite.

If the United States was out of touch, the Shah seemed even more so. He tried to blame the unrest on foreigners. He even pointed the finger at the CIA.

Precht, by then, the head of the Iran desk at the State Department, was horrified.

"Here we were depending on this autocrat to protect American interests in a very key part of the world and it appears that he was some kind of nut! This job was going to be a lot more complex than I thought it would be," he says.

During the course of 1978, the demonstrations continued. The Shah declared martial law.

Then came Black Friday.

On September 8, 1978, crowds gathered to demonstrate in Jaleh Square in downtown Tehran. Government troops opened fire on the protestors. Hundreds of people were killed.

Sick says it was the moment of no return.

"It's extremely ugly and it captures the public's imagination the way nothing had before. I think that's the point when it turned into a revolution," he says.

Iran's troubles could not have come at a worse time for the United States. The Carter Administration was consumed by its quest for an Arab Israeli peace. The Jaleh Square massacre occurred during the Camp David summit. Carter placed a phone call to the Shah, but there wasn't much he could do to stop the revolution's momentum. US policy was simply to continue to support the Shah.

"You couldn't even raise the possibility of an alternative. Partly because it would be seen as defeatism, you would be in effect pushing the Shah over the cliff if you like. And secondly because nobody had an answer to that next question, that okay if you're so smart and the Shah isn't going to make it what do you suggest? There wasn't any answer to that question. We had made no preparation. There was no plan B," Sick says.

The demonstrations continued to build. Millions of people at a time were turning out onto the streets. The Shah asked Saddam Hussein to expel Khomeini from Iraq. Saddam obliged him. The Ayatollah made his way to France. His followers kept up the pressure. They called for independence from the United States, for an end to the monarchy and for the formation of an Islamic government.

On January 16, 1979, the Shah announced he was leaving Iran. He said he was going on vacation, but Iranian people reacted as if it was the end of his reign.

"There was initially a great explosion of celebration and joy," says Bakhash, who worked as a journalist in Tehran at the time. "I was on one of the main streets of Tehran and not only did I suddenly see these newspapers with the huge headlines "the Shah is gone" but there was an explosion, a cacophony of car horns and celebrations and people dancing in the streets."

The Shah gave a strange ethereal interview to the BBC as he left.

"I am dedicated to my country because this is the most beautiful thing that could happen. What could I take away with me when I go in the grave. Not even a dress. Maybe just a piece of white cloth that's all. So I am philosophical enough to know these things. And I have enough for the earthly needs. So what I have got to take with me into the grave is history."

Just before he left the Shah appointed a new prime minister from the opposition. Shapour Bakthiar was supposed to form a government of reform. But the move did nothing to placate the masses.

Iranians continued their mass protests. And they focused on Khomeini's return. In France, the cleric granted interviews. He talked about his plans for an Islamic republic. Khomeini advisor Ibrahim Yazdi often interpreted the Ayatollah's remarks for the Western press.

"The kind of government we have in our mind is the type that basically was established at the early time of Islam and the time of the Imam Ali may peace be upon him at that time there was no fear no frightening issues everyone was secure under those society," Yazdi said.

On February 1, 1979, two weeks after the Shah's departure, Khomeini made a triumphant return to Iran.

The BBC's John Simpson was on the plane that carried him back from Paris.

"It must have been two or three million; it was an enormous, a huge, a fantastic crowd it wasn't just a political event it was a sort of messianic event people really felt something extraordinary was about to happen and you know life itself was going to change," Simpson says.

Ten days later, in a final burst of chaotic street fighting, the last vestiges of the previous regime were swept away and Bakhash says the landscape changed overnight.

"We went to bed one night in Tehran and woke up the next morning and there were revolutionary committees carrying guns everywhere. Revolutionaries were in control of the military barracks, of ministries, of radio and television. So although the buildup to the revolutionary moment took an entire year when it came it was very sudden and very quick," he says.

The US foreign policy establishment was stunned. US officials were simply blindsided by Iran's upheaval. Scholars look back on the episode as a massive intelligence failure.

Sick says he doesn't think the United States could have stopped the Iranian revolution, but the consequences of America's single-minded obsession with the Shah were considerable.

"There was no doubt in anybody's mind that the fall of the Shah and the replacement of his closely allied government with a government that was unremittingly hostile to the United States and all it stood for was a strategic disaster of major proportions. Our whole security structure in the region had been built around Iran and particularly around the Shah and that was gone," he says.

What US policymakers didn't know is that things would only get worse. Nine months later Iranian students would take dozens of Americans hostage at the US Embassy in Tehran. US-Iranian relations have yet to recover.