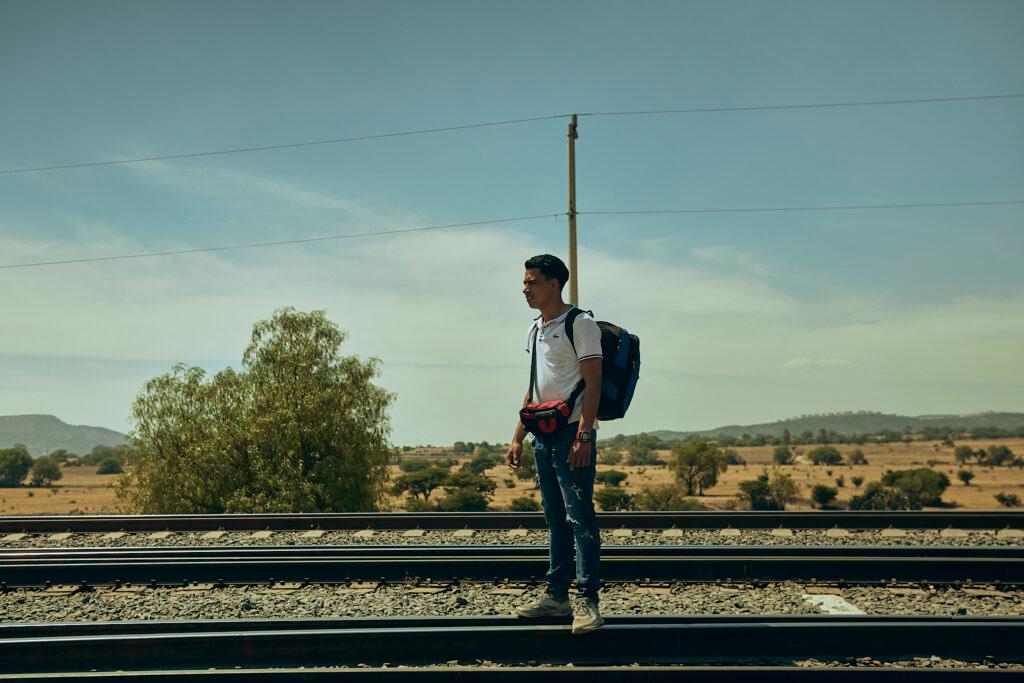

Josmar García, a 26-year-old migrant from Venezuela, showed no doubts when asked to name the most difficult part of his journey through eight countries en route to the United States: “It’s Mexico,” he said.

García explained that encounters with immigration authorities and cartel members are common across the country. “You need a lot of money to bribe officials or pay ransom money,” he explained.

“It took me three days to pass the Darién [Gap], and I have been stuck in Mexico for three months.”

Lucero Hernández, migrant

Other migrants traveling to the US southern border by land agree.

For Lucero Hernández, crossing Mexico has proved to be even more challenging than going through the Darién Gap, the dense jungle that separates South and Central America.

“It took me three days to pass the Darién, and I have been stuck in Mexico for three months,” she said.

In recent months, Mexican authorities have increased efforts to impede the transit of migrants, per request of the Biden administration.

Last year, the National Institute of Migration stopped issuing special humanitarian permits that allow migrants to move freely through Mexico. Without those permits, they are not allowed on public buses. Motorists also face fines if they give rides to undocumented people, and the police conduct frequent searches at security checkpoints along highways to enforce the measures.

If migrants are caught by the authorities, they are usually sent deeper south into Mexico to discourage them from coming to the United States.

In the first two months of this year, Mexican authorities detained migrants 240,000 times, more than triple from the same period of 2023.

“It’s part of a strategy to slow down the pace of migrants,” said Andrew Selee, president of the Migration Policy Institute.

The strategy seems to be working, at least temporarily. The US saw a significant drop in illegal border crossings in the first trimester of 2024.

In March, US Customs and Border Protection made 137,480 arrests of people entering from Mexico between ports of entry along the southern US border, 45% lower than in December of 2023.

It’s a surprising development, because crossings have historically risen in the spring, when temperatures turn warmer.

But Selee was cautious. “We need to see this as a relative shift, because the Mexican government does not have the ability to completely stop most people coming through Mexico, or deport them to their country of origin, nor has large-scale capacity to hold them in detention,” he said.

But the decrease in illegal crossings, even if temporary, is welcome news for the Biden administration, which has been facing mounting pressure on immigration ahead of elections later this year.

In late 2023, border crossings reached record-high levels, surpassing 300,000 in December. The increase led US officials to temporarily shut down some ports of entry.

Cargo trains reemerge as popular mode of transportation

It’s not uncommon that migrants crossing Mexico on their way to the United States are victims of kidnappings and extortion.

Andreína Rodriguez, a migrant from Venezuela, said she was even advised to take birth control pills because “everyone says rape is on the rise in Mexico.”

“The real danger is in the criminal groups that prey on migrants, some of them organized crime, but a lot of local criminal groups, as well,” said Rafael Velásquez, the country director of the International Rescue Committee in Mexico.

“In some cases, there have been public authorities involved in this, too,” Selee added.

To sort out these dangers, migrants García, Hernández and Rodríguez decided to ride on the roof of cargo trains to reach the north of Mexico.

The train ride itself comes with its own risks: falling and losing a limb or suffering from hypothermia or heat stroke after being exposed to the elements for so many hours.

But this mode of transportation remains popular among migrants who are traveling on a budget and want to avoid immigration officials and cartel members along their route.

However, Mexican authorities have also been patrolling the points where migrants take these trains, forcing people off and onto buses headed back to the south of Mexico.

Many migrants who face this fate simply try again to cross Mexico as many times as it takes, to reach the southern US border.

Related: How the asylum system became the main avenue for mass migration to the US