‘I just got completely blasted by love’: People in the UK attest to the ways that spirituality is evolving

On a Sunday night at St. Luke’s Church in east London, a group of 30 people — ranging from their late teens to early 30s — mingle in a recreation room against a backdrop of purple strobe lights and hip-hop music.

Some people close their eyes and reach their hands out, absorbed in the scriptural lyrics. Others dance. They’re part of the evangelical congregation, Kingdom Overflow, which describes itself as a church for an emerging generation.

“Kingdom Overflow was set up because in our country, there is a huge generational gap among those who go to church and those who don’t,” said 29-year-old congregant Joshua Morris.

The Church of England was founded in the 16th century under King Henry the VIII and has been the state religion ever since. But today, church attendance is at an all-time low, and parishes across England are closing at a record rate.

Linda Woodhead is a theology and religious studies professor at King’s College London.

Evangelism is having a moment, she said: “They’ve really had a sort of takeover of the Church of England.”

But that embrace of evangelism can also alienate some. For example, the evangelical branch of the church is not accepting of same-sex marriage and female priests, which have caused some deep divisions.

“You know, it doesn’t really like to tolerate the other kinds of Christianity, and it tends to push them out. And people leave if they don’t go along with that version of the faith.”

Today, some churches and faiths and alternative forms of spirituality across the UK are seeing growth.

The World talked to a variety of congregants, clergy members, Muslims, atheists, humanists and pagans, of all ages, about their spiritual beliefs and how it fits into the bigger picture. Hear more from them below.

Joshua Morris, 29, congregant, Kingdom Overflow, east London

Morris said that he grew up going to traditional church services regularly with his parents, but he never felt connected to it.

“I couldn’t match up science and Christianity and science and God. And I was convinced that actually, I think science disproves God.”

Then, he attended a Kingdom Overflow service at 15.

“I just got completely blasted by love, like it was on me and in me. It was such a truly spiritual experience,” he said.

The congregation is evangelical.

Evangelicals form one of the church’s three main branches, which also includes the traditional Anglo-Catholics and more progressive-minded liberals (or, the broad church) who tend to be more open to change within the church.

Evangelicals have always been a minority within the Church of England but their influence has grown exponentially in recent years. Learn more:

Simon Foster, mid-50s, Anglican priest, Church of St. Chad’s, Lichfield, England

Foster, who found religion later in life, has been a priest for three years. His family isn’t religious, though.

“I think they all look at me and think I’m a bit mad, really. But for me, faith is incredibly powerful and incredibly important because it’s about two things. It’s about love and truth, and those just seem like the things that really matter.”

That may sound a bit preachy, though that is his job after all.

That being said, Foster said that he doesn’t like to evangelize.

“I mean, that’s a classic image of a Christian sometimes. Is the guy on the street corner shouting out or whatever. But the people that I would encourage are the people who want to be good in this world and want this world to be good. Those are the people I would say, ‘Yeah, come and get involved, come and have a look.’”

But he said this is a difficult moment for the church and his congregation at the Church of St. Chad’s in Lichfield, a traditional Anglican church that dates back to 669 — almost a millennia before the Church of England’s founding.

“Somehow, we’ve lost track of the generations who might follow us into worship. And that feels really strange to think about when you’re in a building that’s been here for maybe 800 years on a site that has been a Christian site for 1,500 years, to think about God leading us into a whole new thing,” he said.

A recent survey from the Church of England found that the average age of regular churchgoers is 61 years old. Hear more from this generation about what they see in the church’s future below:

Salman Farsi, mid-30s, chief communications officer, East London Mosque, east London

Farsi is a practicing Muslims of Bangladeshi heritage who was born and raised in London’s East End.

Farsi said 9/11 changed everything for Muslims all over the world. He was just a teenager at the time.

“We witnessed that awful tragedy. But then, the press and the media pointed their cameras at us and at ordinary Muslims, and everything about us was scrutinized.”

For Farsi, growing up in that shadow became extremely difficult.

“For my generation in particular,” he said, “we’re the ‘war on terror’ generation.”

Before 9/11, Farsi said, the outside world wasn’t pressuring him to pick sides or defend his religion.

“I think there comes a time where you just have to draw a line in the sand and look, we need to become this is who we are. This is our identity. This is our faith, and this is what we bring to the table. And we are part and parcel of British society,” Farsi said.

Farsi and another younger member of the mosque talk more about being Muslim:

Alexander Hall, 28, conductor and keyboard player, London Humanist Choir, London

“I think humanism for me is closest to what I feel, which is that I’m very much against dogmatic opinions from anyone about anything,” Hall said.

Humanism, he said, focuses on basic human values such as happiness, empathy and fulfillment.

The basis of humanism can be found in ancient Greek philosophy from thinkers like Socrates and Aristotle.

Humanists don’t believe in a God or an afterlife. They don’t have a regular place of worship, and they favor science over the supernatural.

Humanism doesn’t offer easy answers, Hall said. For example, if someone dies, humanism is not going to say where they went to after death, or that they went anywhere at all.

Hall said that humanists need to work harder to find ways to comfort people who are grieving and struggling. But for now, humanism, and the choir, does offer a sense of community, he said, centered on shared values outside of organized religion.

Other choir members echoed many of Hall’s sentiments:

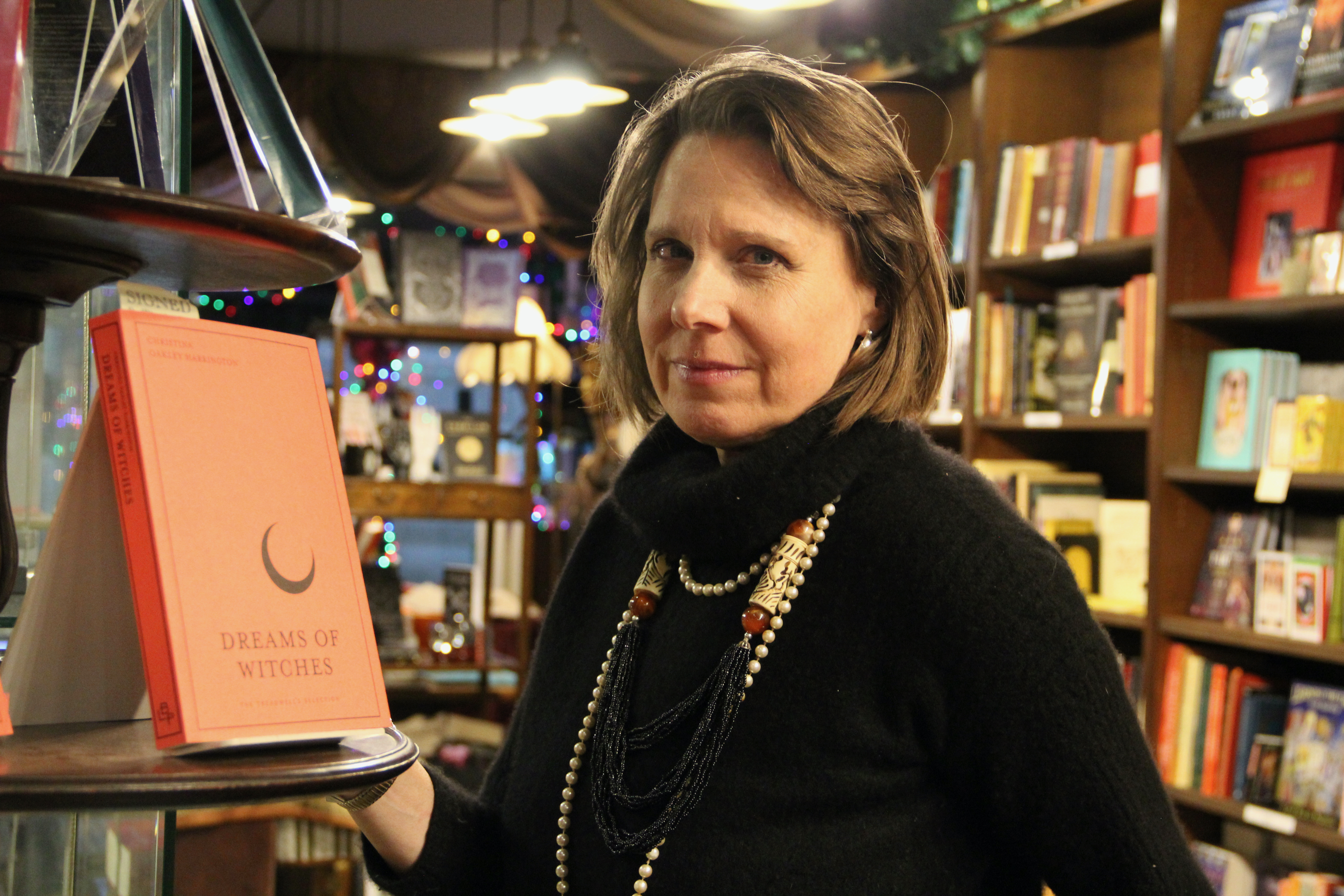

Christina Oakley-Harrington, owner, Treadwell’s, central London

Oakley-Harrington used to be a professor of medieval history at a Catholic university.

Back then, she hid from her co-workers that she was a practicing pagan — with a belief that the divine is in the natural world as opposed to some far-off place.

“It would have been deemed to bring the university into disrepute,” she said.

Today, Oakley-Harrington is the owner of Treadwell’s, an occult bookshop in central London.

Oakley-Harrington said that growing interest from young people is helping destigmatize paganism.

“Often, when younger people come in, they’ll say, ‘I am drawn to this. I don’t quite know where it’s going to take me.’”

Part of it, she said, is the fact that there’s a big ecological element to paganism. And with the ongoing climate crisis being a top concern for many young people, Oakley-Harrington said, it’s no wonder they’re turning in this direction.

Others at the occult bookshop discuss what makes alternative forms of spirituality appealing: