For 7-year-old Katya Rybalka, her school day begins in a classroom located deep underground inside the metro system in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

The first-grader sporting a Princess Elsa shirt greets her teachers and settles in for an English language lesson.

She says she likes coming to school in the Kharkiv underground.

Kharkiv’s stations were used by thousands of residents as bomb shelters at the beginning of the war. Kharkiv remains a target and most school children in the city are getting their education online.

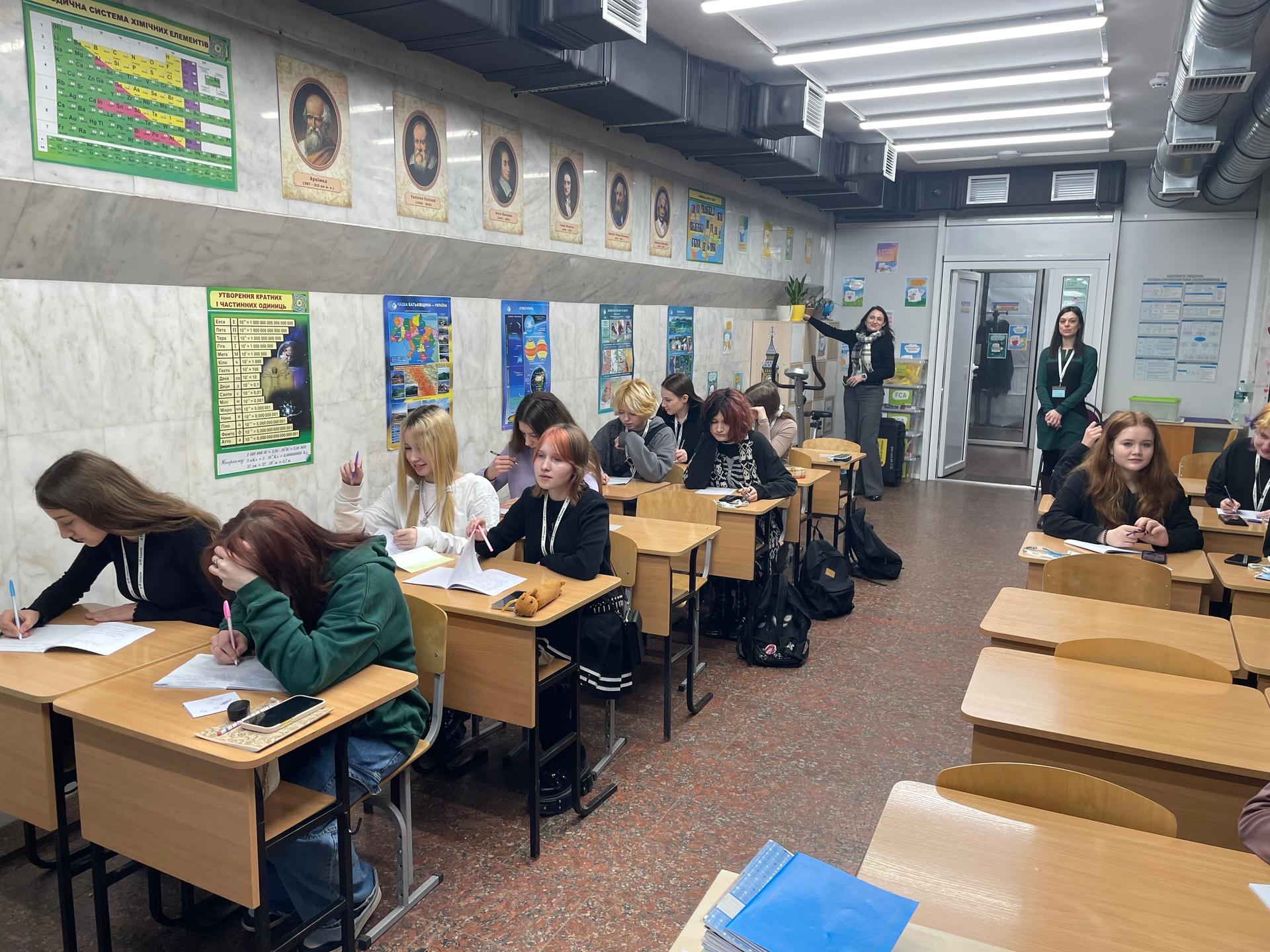

But this fall, Kharkiv launched an underground school system and one of the locations is the Peremoha metro station. They transformed offices into classrooms, improved ventilation and put up colorful posters.

Now, more than 2,000 students attend classes at 5 different locations within the city’s metro system.

Rybalka is from the Kharkiv region, but during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, her family has had to move multiple times. She said the moves were hectic and listed all the family members that fled together: her parents, grandparents, cousins, and her family’s puppy, Richie.

She said her parents were worried but she felt differently. “I just watched cartoons and I didn’t worry,” she said.

But the war does impact kids on many levels.

Rybalka’s English teacher, Vyacheslav Timofeev, said returning to in-person school has been critical.

“It is very beneficial for them to have live communication with adults, with children of their age, and this is right for their socialization and future.”

Timofeev said that along with teaching in the subway, many other things have changed over the last two years, including hearing students talk about war.

Timofeev, who teaches first through fourth grade, said his students talk about it often. “They don’t have, you know, any hatred, or any particular fear. I don’t see that they are afraid of something, they just talk about it like it’s normal stuff,” he said.

The war sometimes comes up in class in unexpected ways, Timofeev said.

One day, students were asked to draw pictures of their favorite toys. The boys mostly drew tanks, he said. When he asked one student why tanks were his favorite toy, he answered, “to kill enemies.”

Timofeev said he’s seen other changes in the students since coming back in-person last fall. “They were very quiet, you know. Even now, half a year later, we have some children that almost don’t speak.”

He said it’s a challenge for the psychologists — there’s one in every classroom within Kharkiv’s underground school system.

“We’re with the children all the time,” psychologist Victoria Fedyanina said. “We greet them in the morning, we’re with them in class, during breaks, and all day, until they go back home to their parents.”

Fedyanina said that the younger kids are going through an adjustment period. They’ve missed a lot of school because of the pandemic and then the war.

“Many of the kids don’t sleep well at night,” Fedyanina said. “There are air raid sirens, and some of them hear the explosions.” When they need to run to bomb shelters in the middle of the night, they’re tired at school in the morning, she added.

Fedyanina also said that many of the kids’ families had to move here from other parts of the country. And some of their parents are in the military. In other cases, a parent may have been killed in the war.

“At 6 years old, you’re supposed to laugh, play, jump, and just be happy,” Fedyanina said, “and we’re trying to give them an opportunity to have a childhood.”

That opportunity has not been lost on ninth grader Anastasiia Doroshenko.

“I don’t even know exactly how to explain it, so it’s some kind of a miracle,” she said.

Doroshenko said that over the past two years, she remembers hearing big explosions near her home three times. Each time, she feared for her life — and that’s had an impact on her world view.

“I think I became more realistic, and I understand that every time [something explodes it can be bad] … so I think I started to appreciate life more …I understand that the most important thing is people,” she said.

The war is ever-present for Doroshenko, but she said it’s not the only thing they talk about at school. She’d rather talk about her favorite subjects — biology, English, Ukrainian language and literature — just not math.

And for a moment, Doroshenko sounds like a ninth grader anywhere else in the world — complaining about math and imagining her future.

Editor’s note: Volodymyr Solohub contributed to this report.

The World is an independent newsroom. We’re not funded by billionaires; instead, we rely on readers and listeners like you. As a listener, you’re a crucial part of our team and our global community. Your support is vital to running our nonprofit newsroom, and we can’t do this work without you. Will you support The World with a gift today? Donations made between now and Dec. 31 will be matched 1:1. Thanks for investing in our work!