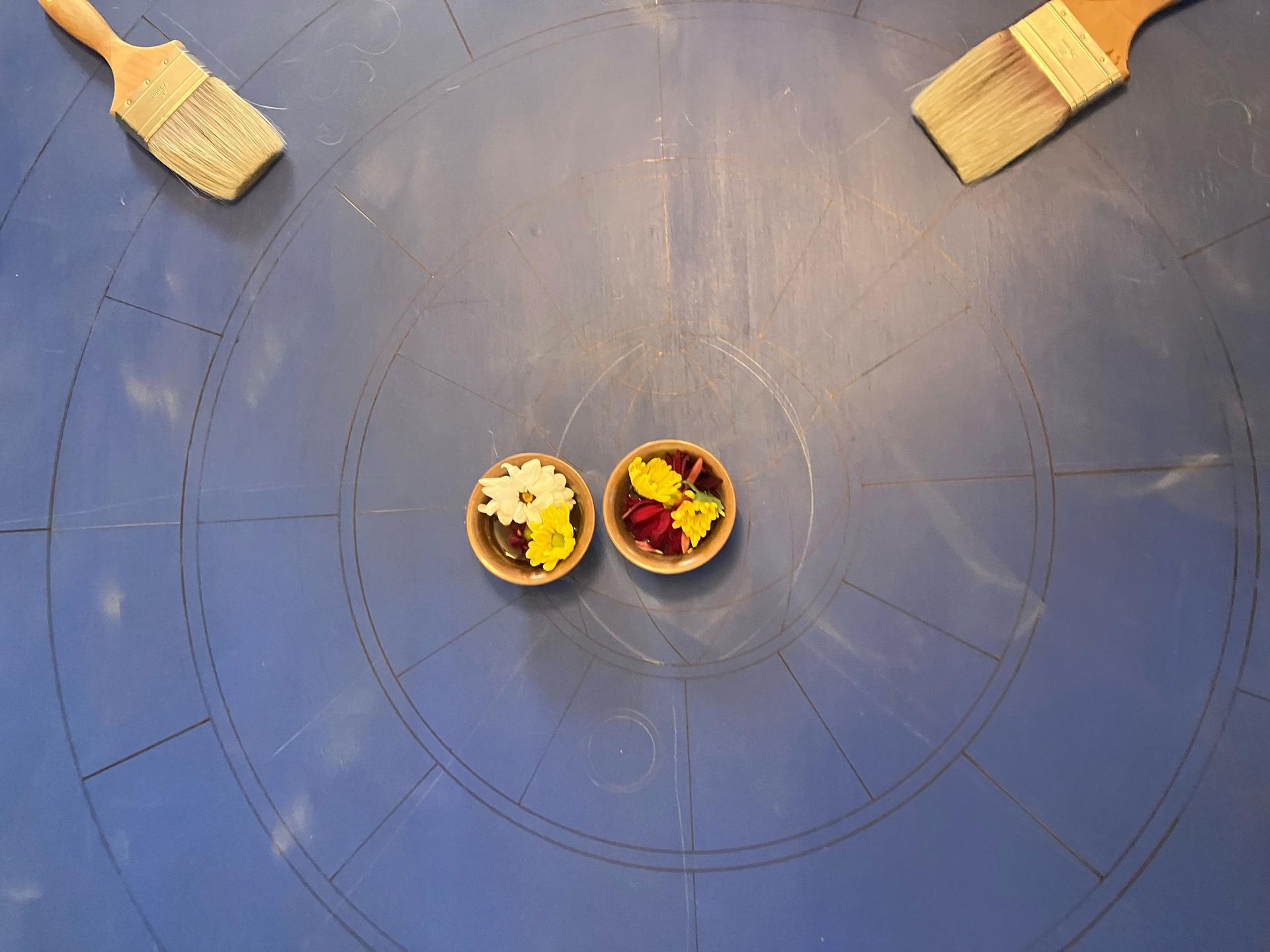

In early September, inside a sun-filled room at the Lake Street Church in Evanston, Illinois, a group of traveling Tibetan Buddhist monks are seated on the floor, leaning over a blank, blue canvas.

They’re plotting the creation of an elaborate sand mandala for world peace.

The seven monks with Drepung Gomang Monastery in Karnataka, India, are on a “sacred arts tour” this month in the US, visiting nine cities through the end of November.

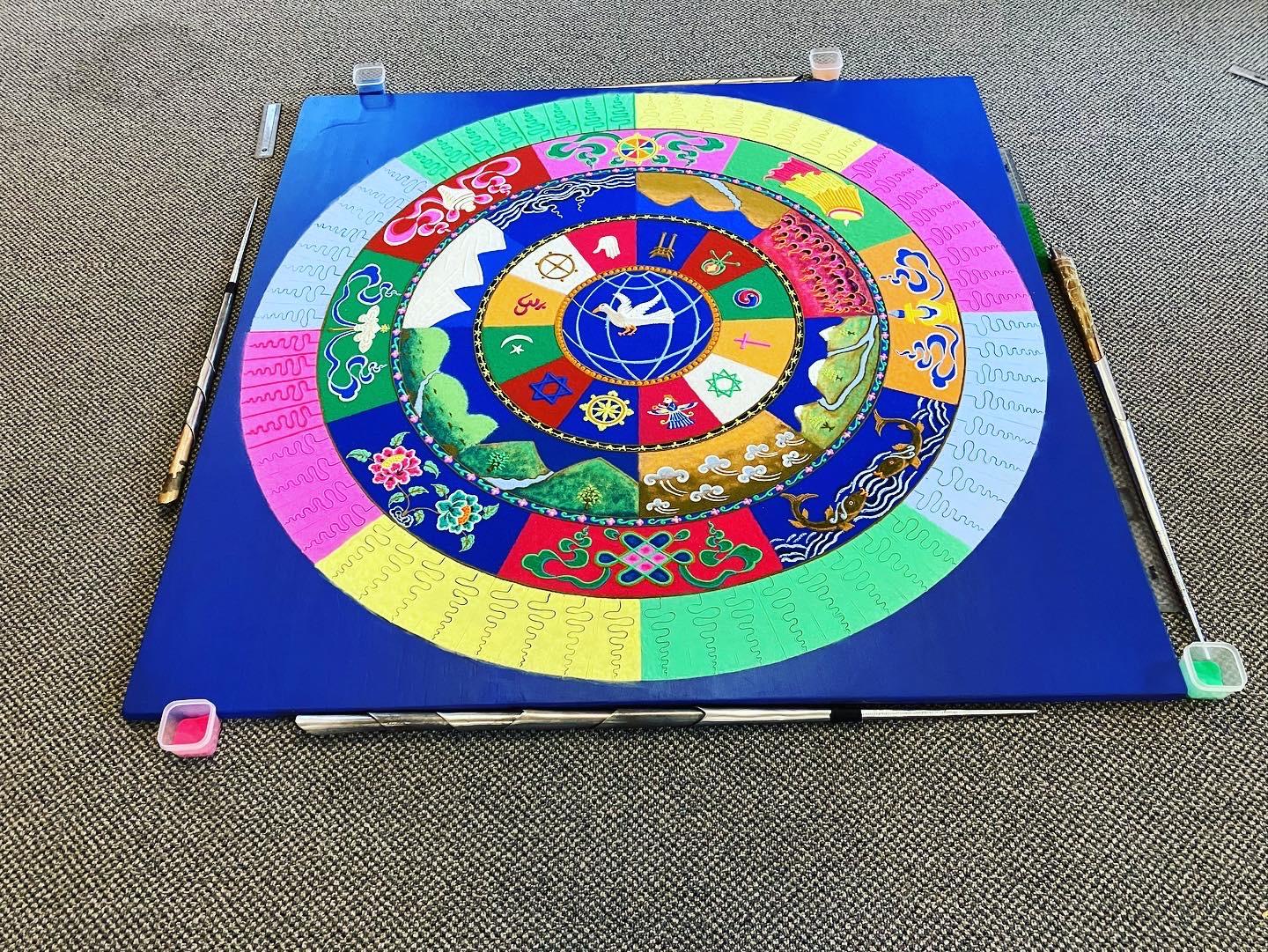

For five, full days, they work with intense devotion and concentration, scraping and tapping colorful sand onto the canvas to create a cosmos with symbols of the world’s religions — only to ceremoniously destroy it upon completion.

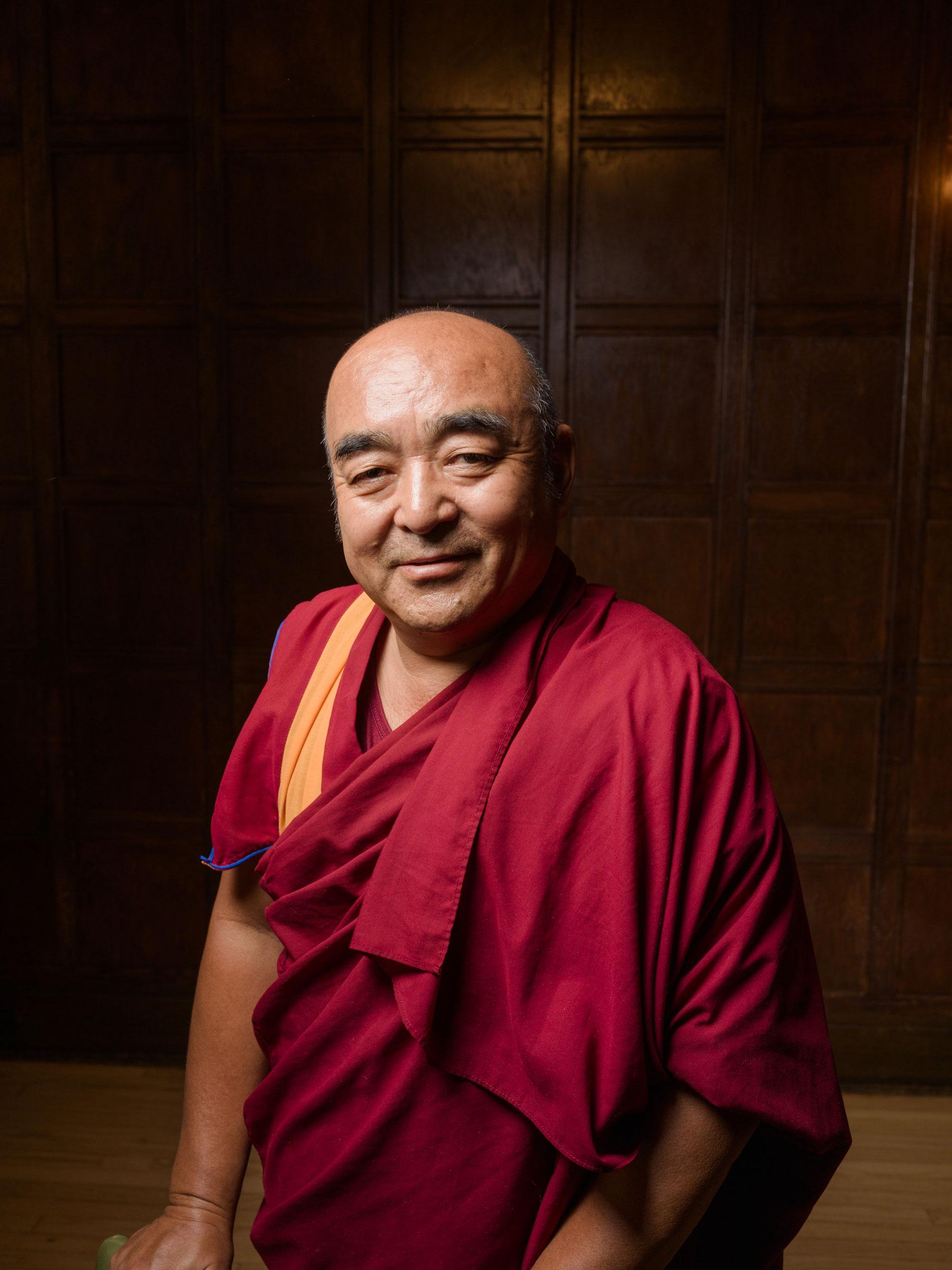

“What this mandala represents is, when we create it, it’s such a beautiful art, but at the end, we will destroy it, which represents impermanence. So, in every day, every life, every minute, something is changing,” said Geshe Khenrap Chaeden, the lead monk.

Their Buddhist traditions like the sand mandala, which dates back about 2,500 years, are under threat as the Chinese government continues to introduce new policies that restrict expressions of Tibetan language, culture and religion.

The monks are in the US to raise funds for their monastery and also express concern for their homeland.

“As we all know, after 1959, Tibetan culture, language, religion, it still was under a huge threat. And it’s still under a huge threat, especially the people inside of Tibet,” Khenrap Chaeden said.

A decadeslong campaign to repress Tibetan identity began in 1950 when China invaded Tibet.

In 1959, on the heels of a deadly Tibetan uprising against the occupation, the Dalai Lama fled Tibet to seek asylum in India and set up a government-in-exile there.

Thousands of Tibetan monks followed in his footsteps, making dangerous treks through the Himalayan mountains to reach India.

Khenrap Chaeden left Tibet in 1990, when he was 17. He has spent the last 30 years at Drepung Gomang Monastery, only returning home once — again by foot through the mountains — to briefly see his parents.

Fellow monk Geshe Sangyal Gyatso, who was born in Tibet and also left in 1990, said China’s repressive policies have intensified in recent years.

“It’s definitely getting worse and more restrictive back in Tibet,” Sangyal Gyatso said.

“For example, back in the day, we could talk a little bit about politics, we could hold a picture of the Dalai Lama, but nowadays, everything is very restricted, also because of technology.”

Even sending a photo of the Dalai Lama through social media is risky, he said.

Strict, new controls on religion

Tibetans saw a brief period of expanding religious freedom in Tibet in the 1990s, according to Robbie Barnett, a UK-based Tibet scholar and researcher at the School of Oriental and Asian Studies.

But since then, the Chinese government has been introducing strict, new controls for the way Buddhism is practiced in Tibet.

“They’re continuing to limit who can become a monk. And you’re not allowed now in central Tibet to become a monk or a nun unless a previous one has died or left the order,” he said. “They’ve capped the numbers of monks and nuns and they’ve capped the numbers of monasteries. So, it’s very, very difficult now.”

Barnett said the Chinese government now appoints Communist Party officials to live inside the monasteries to make sure the monks are following certain ideological guidelines.

“They have to love China more than they love religion. They just have to believe that the law of the land is more important than the law of religion. They have to believe that citizens are more important than monks and nuns,” he said, adding that the monks must be ready to inform authorities of any hint of dissent.

There’s even a police station in every major monastery. Those who violate the Chinese government’s regulations face fines and jail time.

Leaving Tibet is nearly impossible for everyone now, Barnett added. Very few people get passports, and there’s been increasing police presence along its border with Nepal since 2008.

Tibetan boarding schools under scrutiny

In late August, the US State Department announced visa restrictions for Chinese officials in response to government policies in Tibet.

Specifically, the US mentioned the “forcible assimilation” of Tibetan schoolkids in state-run boarding schools.

Lhadon Tethong, director of the Tibet Action Institute, said the schools are part of a larger effort to erase Tibetan language, culture and religious practices.

Tethong said the Tibet Action Institute released a report on the sweeping scale of these schools in 2021, and the results were “shocking.”

“We figure at least 80% of all 6 to 8-year-olds are now living separated from their parents in their communities in these schools, with an intensive, political curriculum,” she said. “It’s all about indoctrination, along with Chinese culture and language.”

These schools essentially aim to take the “Tibetan out of the child,” she said.

“It’s unacceptable. It’s the worst kind of wholesale attack, not just on children but on peoples. And it has to be stopped.”

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin recently denied the US State Department’s accusations of “forced assimilation” at schools in Tibet.

He called it a “pure fabrication,” adding that China “fully protects” the rights and freedoms of all ethnic groups, including freedom of language and religion.

But Tethong said China only gives the appearance of religious freedom in Tibet.

“If you go to Tibet, you’ll see monks, you’ll see monasteries, you’ll see people going to the monasteries. What is not as clear is that the study and practice of Buddhism within the monasteries is being attacked and hollowed out.”

Ancient tradition

Back at the Lake Street Church, on their final day here, the monks recited their prayers before making the finishing touches to the mandala.

They worked with intense concentration to fill in the outermost rings with more details from the “eight auspicious symbols” of Buddhism: pink and green lotus flowers, two golden fish splashing in a blue wave, a white conch shell, a pink and blue knot, a yellow wheel surrounded by green ribbons.

Sangyal Gyatso said that the process itself is a meditation.

“Before we create this mandala [each day], we … pray for world peace and individual happiness. So, during that [time], I also have this motivation for a better world, for peace and love.”

Barb Vaughan, a member of the interfaith-focused church, said it was a profound experience to watch the monks in action.

“For them to be able to create something so beautiful, and not get attached to it, is a model for me. Because I can think about it intellectually, but emotionally, we want to acquire things and hold on to them. So, it’s a good lesson.”

After a closing ceremony, the monks swept up the sand into a swirl of colors toward the center of the canvas and collected it into an urn.

The packed room was struck with awe and wonder.

Shortly after, the monks, adorned in vibrant yellow caps, walked in procession a few blocks to Lake Michigan, chanting and praying as a crowd followed behind them.

At the lake, Khenrap Chaeden poured what remained of the sacred sand into the water, and they all chanted one final prayer for peace.

Although the monks have mastered the art of letting go of the sacred artwork, they hold on to hope for more freedoms in Tibet.

Editor’s note: Tenzin provided Tibetan language translation for this story.