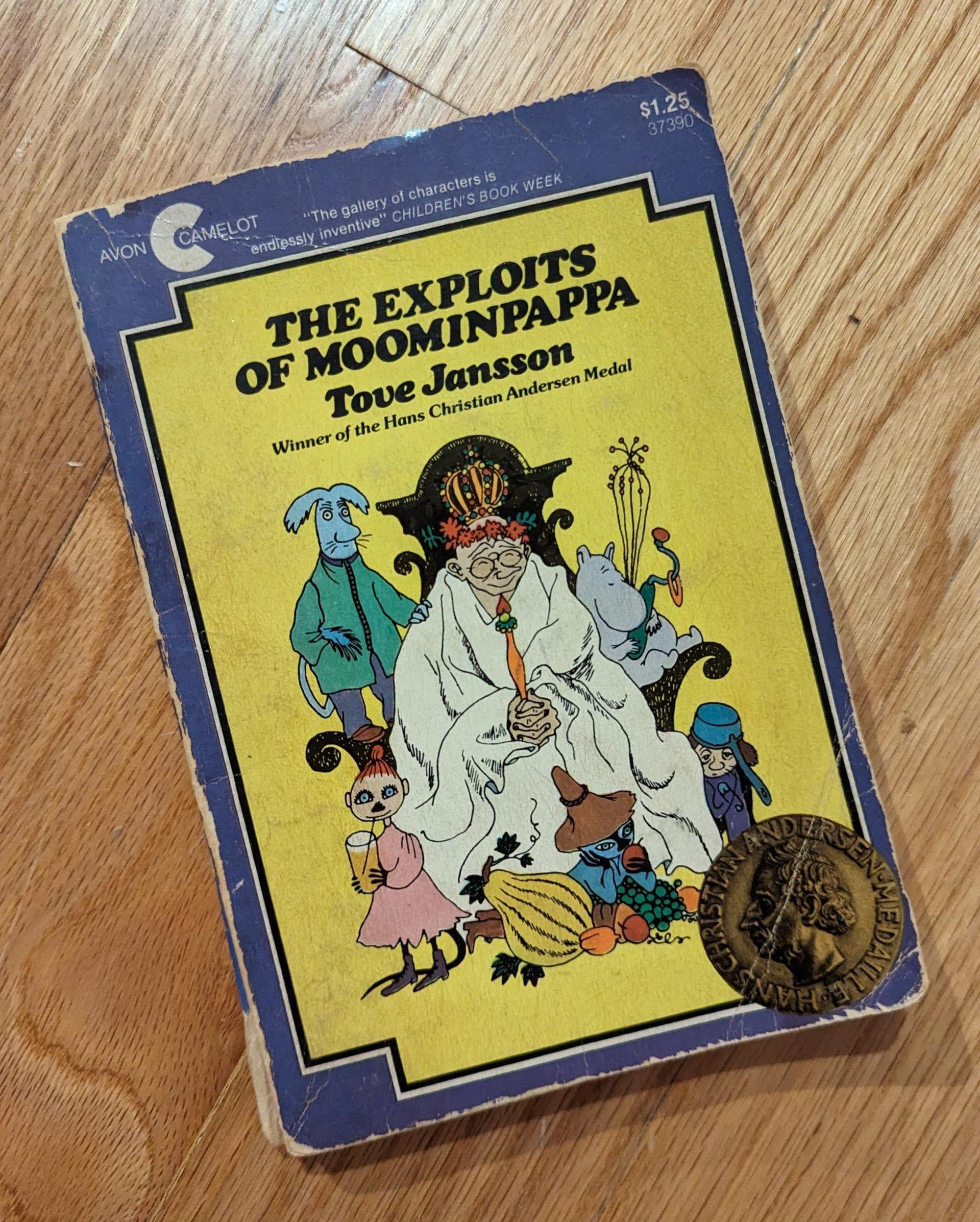

I still own a 1978 paperback edition of “The Exploits of Moominpappa” (later retitled “Moominpappa’s Memoirs”) about the Moomins, a family of hippo-like trolls created by Swedish-speaking Finnish author and artist Tove Jansson nearly 80 years ago.

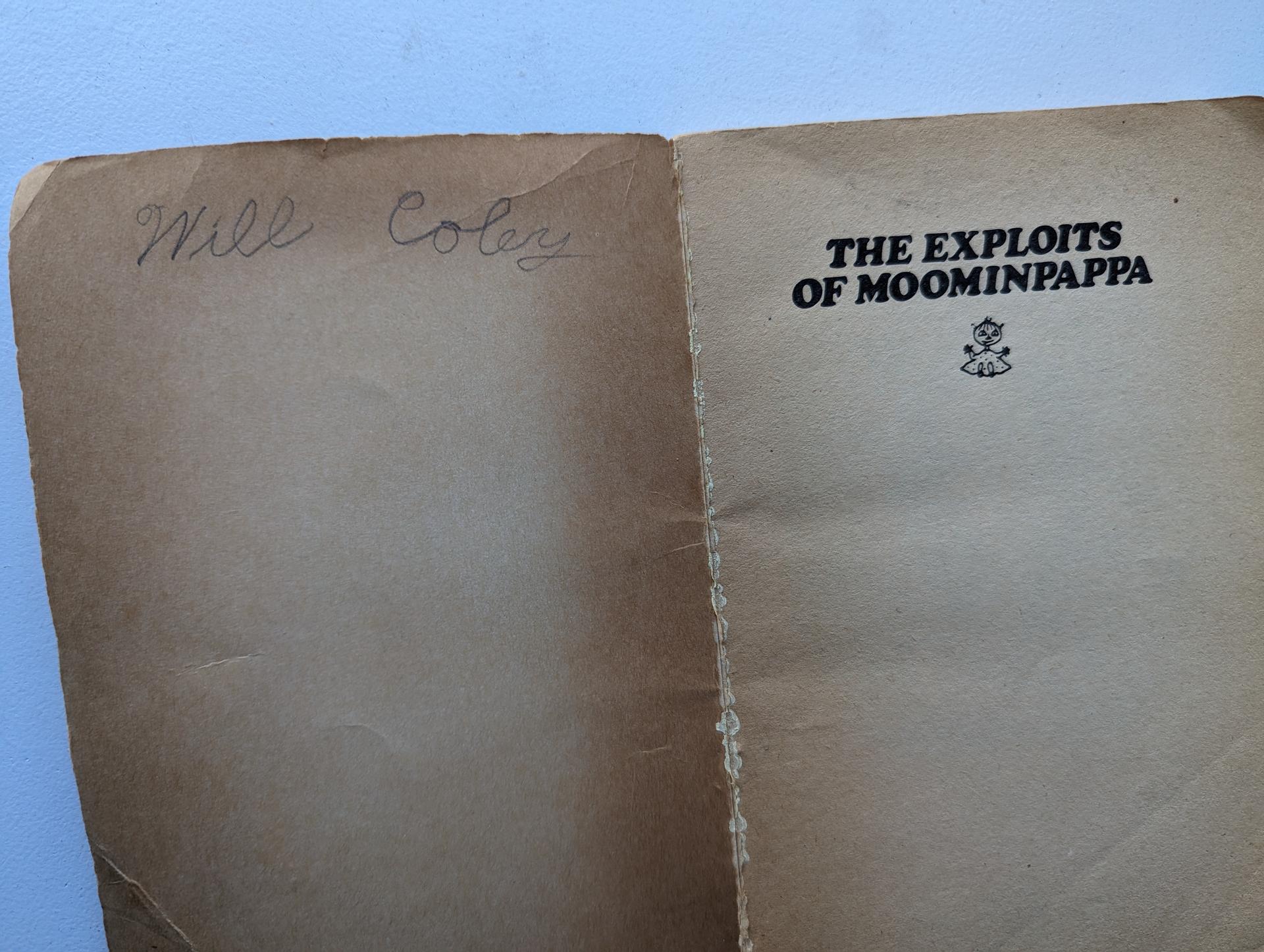

The pages of my well-worn copy are yellowed now, and my signature inside of the front cover is in blocky, awkward cursive.

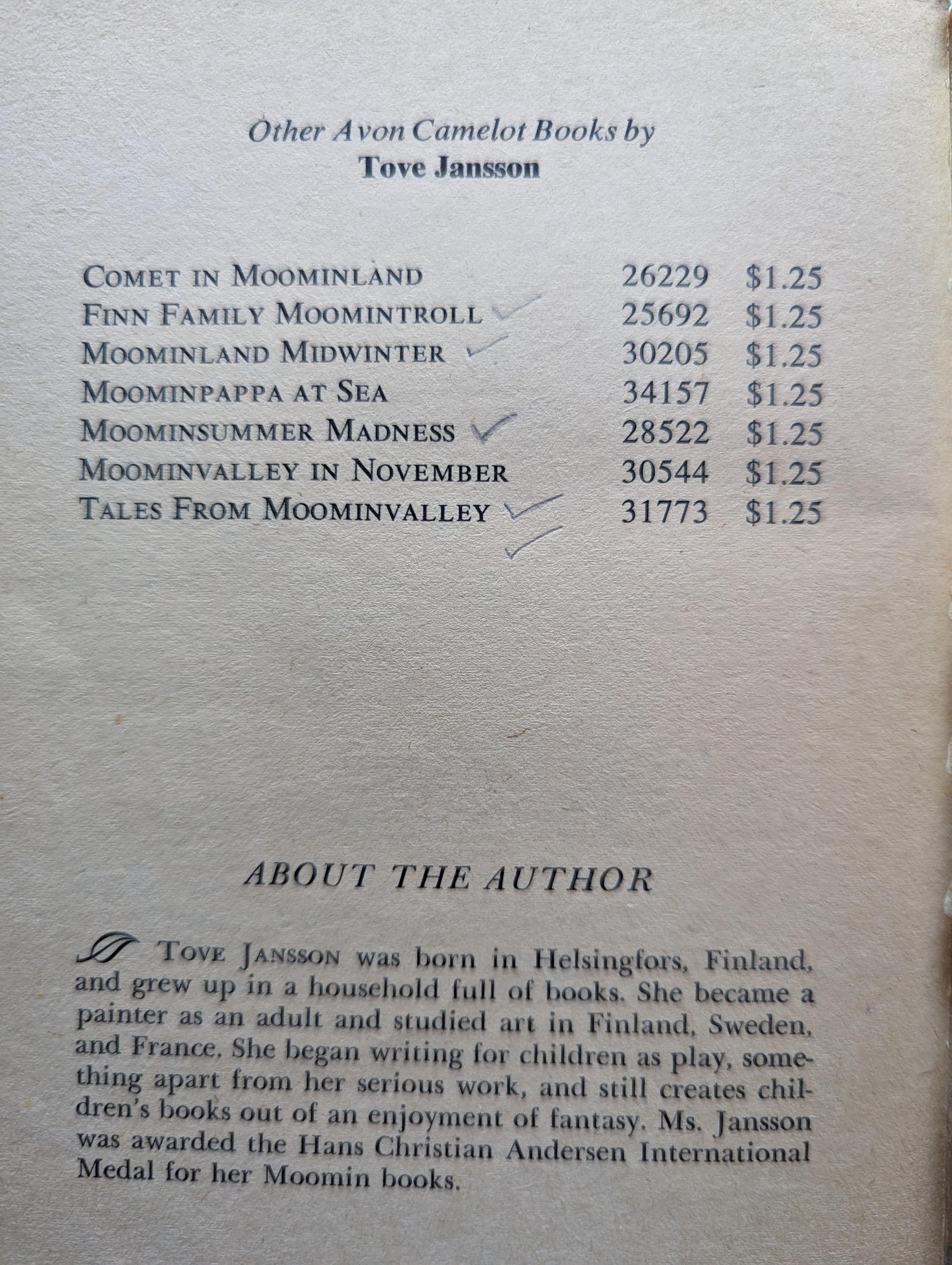

Inside the back cover, I penciled checkmarks next to the other seven books that I eventually also read. (Today, many people include a ninth book, “The Moomins and the Great Flood,” in the canon.)

I’m not quite sure how, growing up in the 1980s in a small town in North Carolina, I found the book by a writer in a far-away country. I distinctly remember looking up Finland in an atlas and marveling that countries can be vertical in shape, not just horizontal.

Although the series had plenty of fans all over the world, it wasn’t well-known in the United States. But more recently, the Moomins have found new audiences here.

Since I started reading the books, the value of the Moomin brand has increased more than 1,000%, growing by double digits every year and is currently valued at well over $700 million globally at retail. According to the Moomin Characters Ltd, Americans comprise the largest percentage of visitors to their website Moomin.com. But Japan is still in a league of its own in buying merchandise.

Nowadays, Moomin books are available at most bookstores or libraries (even if the staff aren’t aware of them) in the US. Earlier this year, Barnes and Noble announced a promotional campaign for the Moomins.

Also, Jansson’s novel for grownups, “The Summer Book” is going to be made into a movie starring Glenn Close. And, “The Moomin Phenomenon” is a podcast hosted by Lily Collins and Jennifer Saunders.

It’s hard to say why these books, first translated into English in 1950, captivated me. It wasn’t because the Moomins themselves were cute and round (which is one theory about why they’re popular in Japan).

My favorite characters were not Moomins: Instead, I was drawn to Snufkin, the free-spirited, outdoorsy friend of Moomintroll, and the Groke, the monster who everyone fears but who is actually freezing because she’s so lonely.

I love the series because of something that I now call a “Nordic sense of place” — a feeling of quiet, low-level angst that’s soothed by nature.

Back then, the little I knew of the author and illustrator Jansson was from the short paragraph inside the back cover. I love the sentence, “She began writing for children as play, something apart from her work and still creates children’s books out of an enjoyment of fantasy.”

Now, I notice the present tense there because she would have been alive when I read the books. She died in 2001. I couldn’t imagine how someone could create such compelling characters with strong personalities, odd shapes and funny names.

As an adult, I learned that Jansson was openly bisexual. Two of the characters, Thingumy and Bob, may represent her and her first partner. Tooticky, another character in one of the books, was based on her second partner, Tuulikki Pietilä, whose nickname was Tooti. There’s also a theory that Snufkin and Moomintroll were more than friends since they often express their love for each other.

Years later, when I was living in Santa Monica, California, I saw someone wearing a Moomin pin in a coffee shop. I just looked at her and shouted, “Moomin!” and she shouted, “Moomin!” back and we had an immediate connection and conversation. It was a rare occasion when I found someone who knew about the books.

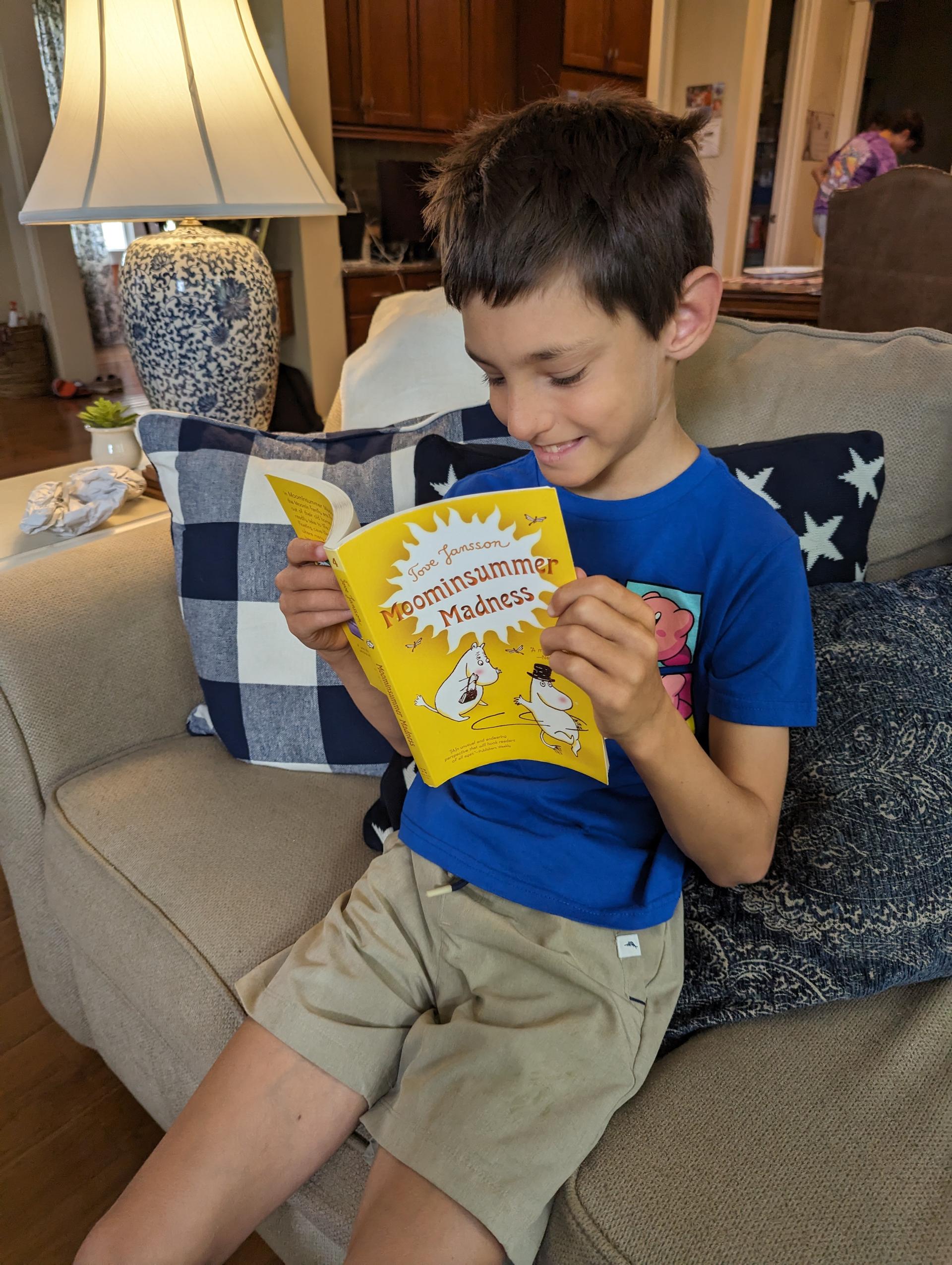

I’ve done my own Moomin outreach. I gave Moomins books to my cousin Zachary Thomas (pictured). When I interviewed him for The World, he said American kids “might love magical stories, especially Moomintroll.”

But he thought they’d be better if there was a big battle with the bad guys, like the Groke.

“Older kids might like it because they love fighting … especially me,” he said.

I never paid much attention to the comic strips or the animated TV shows because I’m a bit of a Moomins purist. I’m not sure I could handle visiting the Moominland theme park in Japan. Something about the repackaging of the characters into 3D, colorized versions beyond Jansson’s simple, black-and-white illustrations feels wrong to me. Like it’s missing the point.

I realized it was time to look into why so few Americans know about the whimsical Moominvalley even today. Though, the internet has made it easier for fans to find each other.

Newer fans like Devon Dunn, who works at an independent bookstore, report that Tumblr was instrumental in helping them discover the Moomins in the last few years.

Lesley Palin is based in the UK and manages The Moomins Appreciation Group on Facebook, which has more than 14,000 members.

“We have definitely seen an upswing in joiners,” she wrote to me.

When I connected with Roleff Krakstrom, the managing director of Moomin Characters Ltd, I asked him why it’s taken so long for the Moomins to infiltrate the US. He wonders if the American English-language market was so strong, it was just too difficult for foreigners to penetrate.

“But we don’t follow the metrics of entertainment conglomerates and investors who expect a certain rate of return to measure success,” said Krakstrom, who is married to Jansson’s niece, Sophia Jansson, the president of the board at Moomin Characters.

“This is a family-owned company. We’ve never had financing or sought it. But we’ve had 100% growth every year.”

In March, Jansson’s biographer, Boel Westin, happened to be traveling to New York (where I live). So, I met her and a friend of hers at their hotel and took a taxi together to the Barnes and Noble near Union Square in Manhattan to see the Moomin pop-up.

There were big promotional stickers in the window. But the display was smaller than we both imagined: basically one side of a tall display table. Two women there, from Georgia, said that they learned about the Moomins in Korea.

Westin noticed the familiar book covers. I asked Westin why Moomins were just now catching on in the US.

“Tove was thinking about it in the late 1940s when she was quite young, because she had a friend who had emigrated to New York,” Westin said. “They discussed it in their letters, but it never went further than these discussions.”

But neither had any contacts in publishing or newspapers so the idea just withered away.

“Later on, in the mid-1950s when she had made a comic strip, she became quite world-famous,” Westin said. “It was published in, I think, over a hundred countries at the same time. And then, Walt Disney wanted to buy the rights for Moomin or the Moomin brand, but she said no. She wanted to keep it for herself and, you know, she wanted her freedom.”

Jansson was first and foremost an artist and among the first generation of liberated Finnish women.

“This is one of my favorites, ‘Moominland in Midwinter,’” Westin said, picking up a copy. “I just love it. It’s very Nordic, actually. You know, the description, or how she describes the winter in color and it opens with this, the sky was almost black, but the snow shone.”

I told Westin my favorite book in the series is, “Moominpappa at Sea,” in which the family packs up and moves to an island with a lighthouse.

She nodded in agreement.

“The whole book is very symbolic, actually,” she said. “I mean, the lighthouse, that’s an old theme in literature. [Tove] was very, very interested in lighthouses. And she writes a lot about how she wanted to be a lighthouse keeper. And I think you can compare a lighthouse keeper to an author because she’s been looking out … watching people and, and showing them the way. And I think in one way, that’s what she’s doing in her books. She can point out the way for us.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?