David Mattey works for a cable TV company in Lima, Peru, making around $500 a month. In March, he got his first loan ever — a $3,000 credit for a motorbike.

Mattey said he wanted the bike to get around faster in the congested city and feel “more freedom.” But he also wanted to earn extra money at night, making deliveries.

“When you’re new in a place, it’s complicated to buy some things,” said Mattey, who is originally from Venezuela and arrived in Peru four years ago. “At first, I didn’t know of any banks or companies willing to give me a loan.”

Immigrants like Mattey often struggle to access loans because they lack a credit history in their new country.

But increasingly, some startups are taking a chance on these newcomers and finding that lending money to migrants can be profitable.

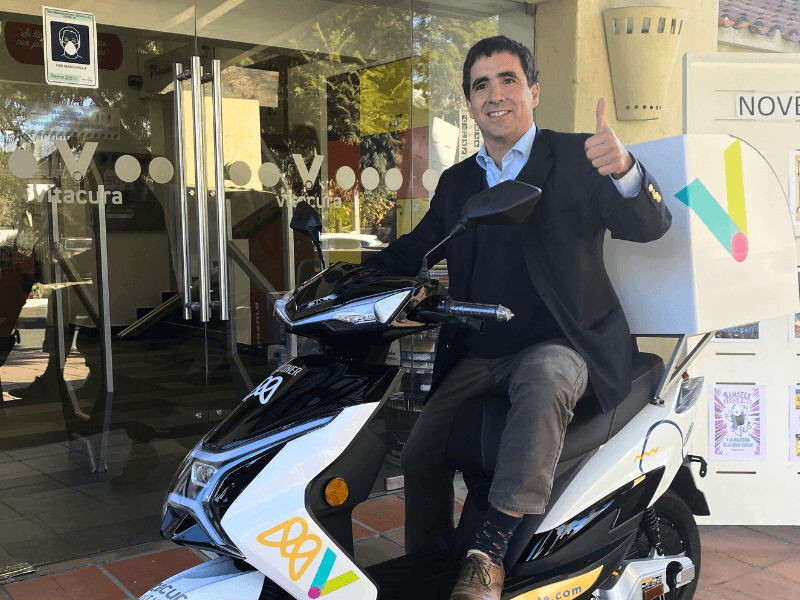

Mattey got his motorbike loan from Galgo, a Chilean startup that has become one of the largest financiers for motorbikes in South America.

With paystubs from his day job and a local ID card, Mattey was able to secure a loan for his medium-sized, 200cc motorbike, which he is paying back in monthly installments of what equates to $105.

“The process was easier than I thought,” he said. “They even made it seem like it was fun.”

Galgo was set up in 2018 by Diego Fleischmann, a Chilean businessman who had previously run an insurance company.

Back then, tens of thousands of Venezuelans arrived in Chile to escape their country’s economic crisis, so Fleischmann and his friend, Salvador Porta, devised a plan.

“We started with this idea of giving something back to these people who were coming to Chile,” Fleischmann said. “We wanted to help them build a future in our country.”

The company started out by providing loans for motorbikes, cars and rent deposits. It even lent money to Venezuelan doctors, who needed to validate their degrees in Chile and had to pay for exams.

“It made no sense for us that a Venezuelan doctor was working as an Uber driver to save money in order to pay this fee to validate their titles,” he said.

But the company’s earnings nosedived during the pandemic, as many migrants lost their jobs and had no money to pay back their loans.

There was one exception, though.

Galgo found that its motorbike loans usually performed well — because after they purchased their motorbikes, migrants would immediately use them to work for delivery apps, like Uber Eats and Rappi. So, the company decided to focus on motorbike loans.

“When people make money with the loans that you are giving, they can pay you back much better,” Fleischmann said.

Nowadays, Galgo finances more than 3,000 new motorbikes each month. The company has expanded into Peru, Colombia and Mexico.

But when migrants need loans for other reasons, there are still barriers.

Juan Pablo Luque is an expert on microfinance at Mercy Corps, a humanitarian group that helps migrants and refugees in more than 40 countries. He says that in many Latin American countries, such as Colombia, migrants are denied bank accounts if they don’t have a national ID Card. And that can lead to dangerous situations.

“They tend to go to loan sharks … that require them to pay absurd interest rates,” Luque said. “And that puts them in a very high-risk situation in their communities.”

But Luque said that the barriers to financial inclusion are easing as digital banks start to compete with traditional banks and cater to migrants to build up their clientele.

In the US, for example, Majority has opened thousands of bank accounts for immigrants in the past three years.

The digital bank tries to make things simple: Anyone can open an account at Majority with an ID from their home country and a utility bill showing they live in the US.

“Getting inserted into the financial system is still a huge hurdle for a lot of people,” said Juan Pablo D’Alessandro, the head of new markets at Majority. “And that’s why we’re trying to make a big difference, at least in that aspect of a person’s establishment in the United States.”

Back in Peru, David Mattey said he is still wary about taking out bank loans because of the high interest rates.

But the motorbike he acquired with Galgo is helping him to increase his income and build a credit history.

“I feel happy about my life here,” he said. “I think that eventually I’ll get a bigger bike and move on to new things.”

Jacob Kessler contributed to this report from Lima, Peru.

Related: Migrant farmworkers in Spain living in makeshift encampments have little hope for formal work

Correction: A previous version of this story said that Majority has opened more than 100,000 bank accounts for immigrants. The company said that number was not accurate, and that at this time, it is not sharing details of how many accounts it has opened.