Marta Kostiv quickly finished up lunch in the dining hall before heading off to class at the International People’s College, a residential school located on a tree-studded campus in Elsinore, a historic town just an hour by train from the capital, Copenhagen.

Hallways here are adorned with photos of the hundreds of international students who have attended the school since its opening over 100 years ago, and each corridor is named after a different part of the world.

The IPC, one of Denmark’s oldest folk high schools, focuses exclusively on global affairs, and all classes are taught in English.

Kostiv, a 23-year-old student from Lviv, said that she heard about the chance to study at the IPC when she was still in Ukraine.

“I saw in one of their group chats that IPC is proposing a scholarship for Ukrainian students, so I applied for it, and I’m really glad that I joined this, because I always supported the idea of lifelong learning,” she said.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion began, 27 students from Ukraine have been accepted to study at various Danish folk high schools across the country as part of a special endowment to encourage young Ukrainians to learn about democratic change and civil society-building — a purpose aligned with the overall history and aim of the Danish folk high school system.

Denmark’s 70 folk high schools are residential colleges where young adults come to live and learn together for up to six months with no grades or exams. These schools embody the concept of bildung — a German word for a learning approach that blends personal, civic and moral development through shared values like cooperation, empathy and dialogue.

The idea for the endowment came from a small group of educators in Ukraine with Bildung in Ukraine, a nongovernmental organization that believes that bildung holds the key to the country’s future.

“A very clear message from [Bildung in Ukraine] was to please open your schools for our youth because they need something meaningful to do while the country’s in a state of war,” said Sara Skovborg Mortensen, who oversees international partnerships with the Association of Danish Folk High Schools. “And we need to prepare and democratize [and] build strong individuals for a time after the war.”

A 24-week semester at the IPC costs about $6,500, which the special endowment makes free of charge. Students can apply to attend any type of Danish folk high school; they emphasize everything from gymnastics to the arts to spirituality.

Cooperate, communicate

At the IPC, residents do everything together, sharing meals and cleaning up in the kitchen, working on class projects, attending cultural nights, hanging out in the library and partying together on the weekends.

Students and faculty say the school’s emphasis on small-group dialogue and personal storytelling helps them break through cultural barriers and stereotypes.

“The classes are different, so we have choir, we have intercultural communication, Asian studies, we have all of that, even gardening. And my goal was to try everything I could,” said Kirill Karuna, a 22-year-old student from Kyiv. “You just cannot help but fall in love with this whole concept.”

Karuna originally applied to stay 12 weeks but was convinced to stay the full 24 weeks and said that he does not regret it — he even discovered his love for filmmaking here.

“What I’ve learned about myself is that it’s all right to deviate from society and be on your own,” Karuna added, “but don’t go to extremes and don’t leave the [community] spotlight for too long.”

Kostiv, speaking alongside him, reiterated that point.

“I think that the core thing at IPC is communication, to try to live in a society where different people from different cultures are together and to try to like, somehow cooperate with each other, even if we are all different,” she said.

Kostiv admitted that “even if you move abroad, you can’t get rid of your problems,” she said, adding that she is eager to return to Ukraine, find meaningful work and continue to build her life there.

“The thing I will bring [home] with me is curiosity,” Kostiv said, noting how she was encouraged to explore the arts and try new things.

“I also learned that I’m an introvert, so I don’t need this many people around me all the time,” she said with a smile.

‘Schools for the living’

The 19th-century thinker N.F.S. Grundtvig is credited as the creative genius behind the folk high school system.

“He was a priest. He was a poet. He was a politician. He was a pedagogical thinker. And he was a philosopher. And basically, Grundtvig’s thought was that we need to educate the Danish population — the sons of farmers — who only had very little education at that time,” said headmaster Soren Launbjerg.

In 1849, Denmark made the leap from an absolute monarchy to democracy with the adoption of its first constitution. In 1864, the country lost 40% of its land and wealth after a war with Schleswig-Holstein, a region in northern Germany.

For Grundtvig, these political and social shifts required a new approach to education that would transform “schools of the dead,” — a system based on discipline, grades and even physical punishment — into “schools for the living.”

“He believed very much in dialogue, which is also, of course, the nature of democracy. So, the spoken word is very important in folk high schools,” Launbjerg said.

Grundtvig himself wrote more than 800 songs about Danish identity and history, and these songs are often sung ritually to this day as a starting point for communal reflection, Launbjerg added.

Over time, folk high schools flourished as a fundamental force in the formation of Danish consciousness. Many leaders and activists around the world would later turn to the folk high school system as a working model for civic engagement, nation-building and democracy.

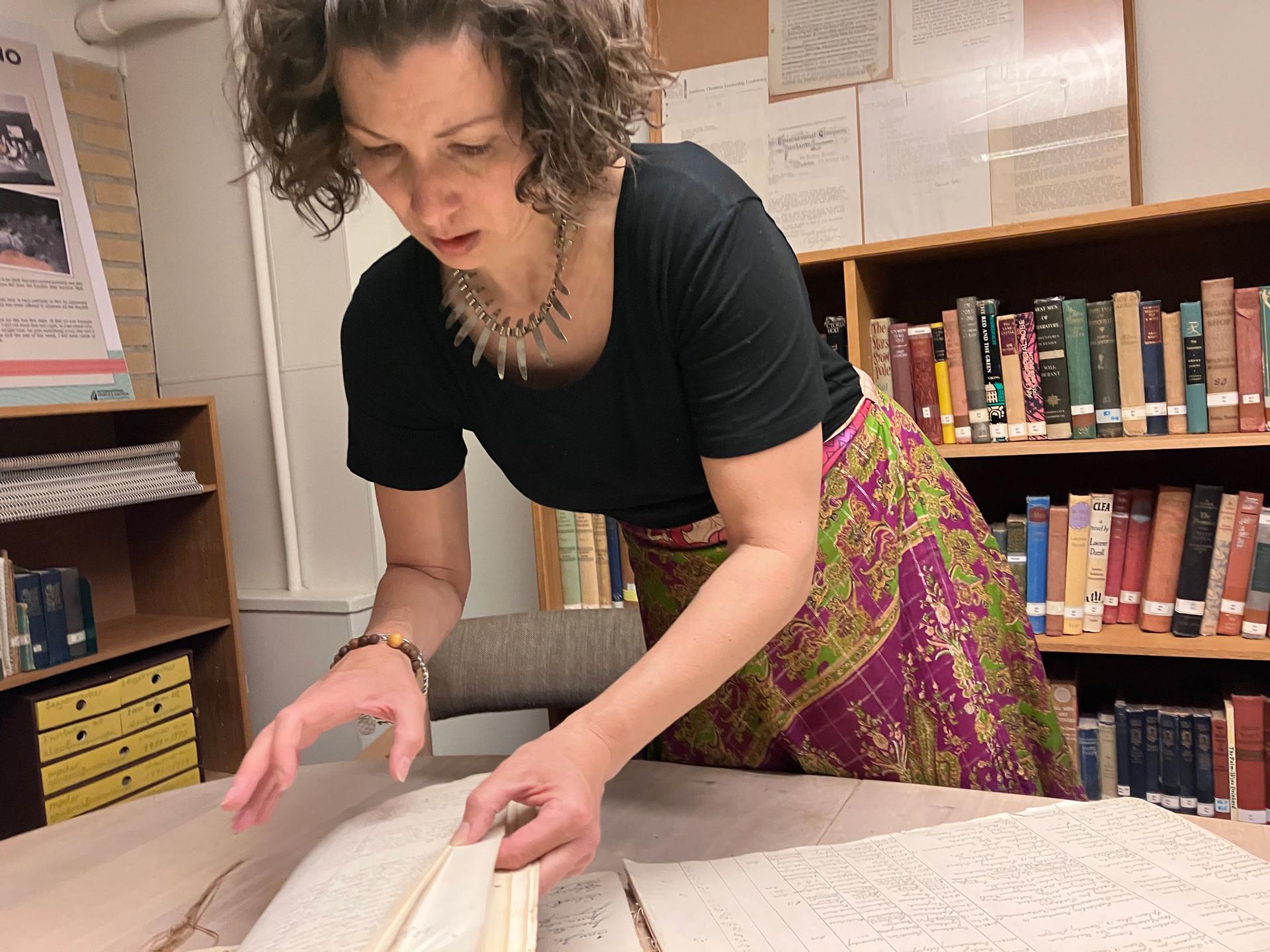

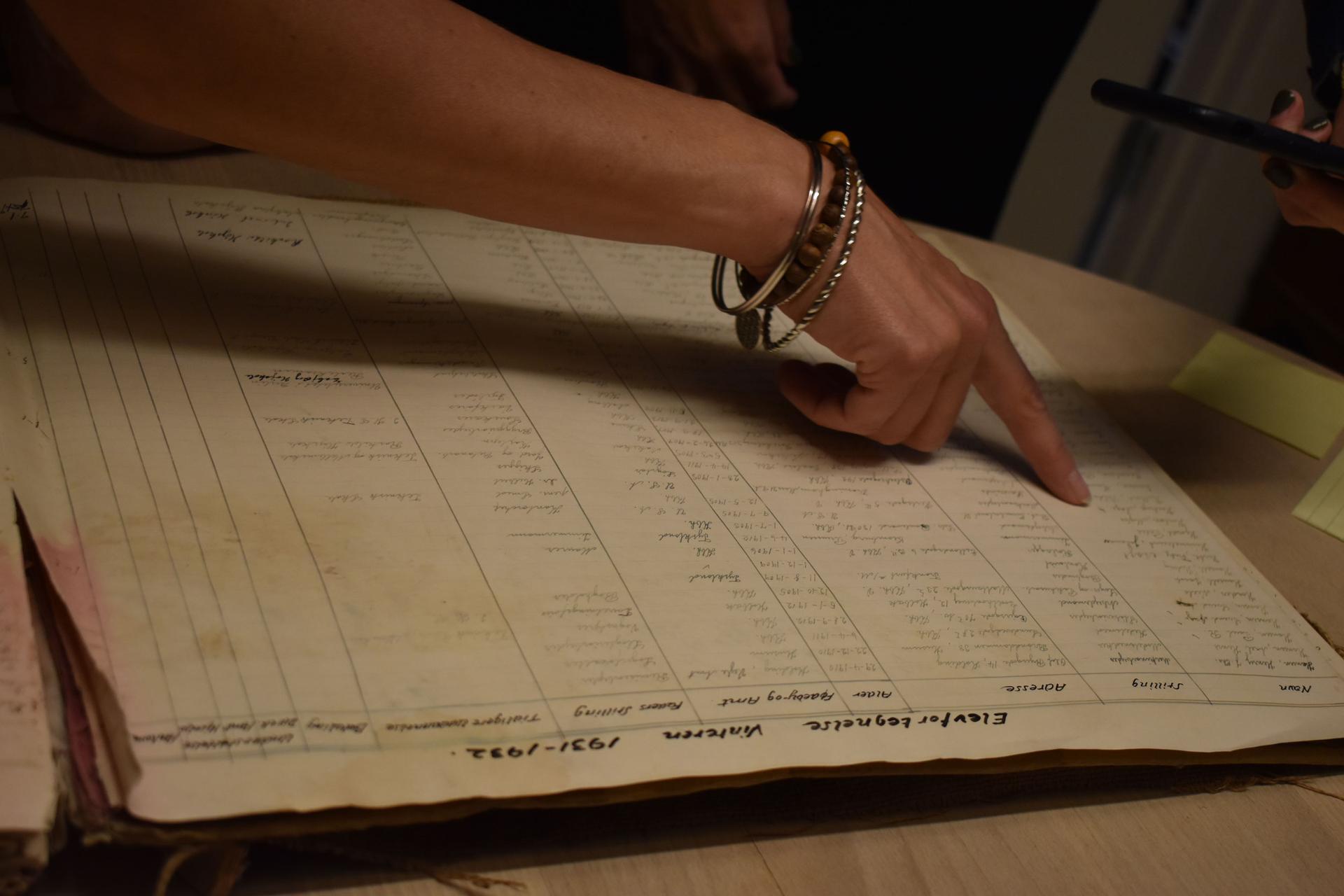

Julie Shackleford, an American anthropologist and teacher at the IPC, oversees the school’s archives in a few crowded offices bursting with historical documents, records and relics.

Shackleford pointed to a framed letter from Martin Luther King Jr. as evidence of the school’s unique role in the American civil rights movement.

She also flipped open to a guest book and traced her finger to the signature of Myles Horton, a student at the IPC in 1931. The following year, Horton established the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, which later became an ideological hub in the US struggle for civil rights.

Shackleford underscored the power of expression as a thread that runs through all revolutionary shifts.

“In Denmark, they went from an absolute monarchy to democracy overnight. How do you participate in that when your voice, you’ve never had a voice before What do you do? So, people needed some training in finding their voice,” she said.

Bildung in Ukraine

Since 2020, a small group of visionaries familiar with the Nordic approach to education have been working to bring bildung to Ukraine by establishing its first folk high school.

Elena Tochilina, one of the founding members of Bildung in Ukraine, has been in residence at the IPC in Denmark since February to learn more about the folk high school system and find ways to adapt to the Ukraine context.

Tochilina said that the need for social change in Ukraine erupted in 2013-2014 with waves of large-scale protests calling for massive political reforms that became known as the revolution of dignity.

“We were very clear that revolutions sometimes are needed, but it’s better to evolve through self-development, through education,” Tochilina said.

About a year and a half before Russia’s full-scale invasion into Ukraine, the group outlined plans, created a road map, established a nongovernmental organization and purchased land for the school.

“When the war started, of course, everything stopped,” Tochilina said.

But the war has also crystallized the need for democratic values in Ukraine, she said.

“And it seems like we’ve got the key, we’ve got the knowledge of how to educate a critical mass of people who will be voters in the future and will be making more conscious choices,” Tochilina said.

The folk high school system offers a blueprint for “installing a new mindset” among Ukrainian youth, Tochilina said, but not everything is directly transferable to a Ukrainian context.

For example, Tochilina said the IPC’s habitual morning singing gave her flashbacks to mandatory, Soviet-era Young Pioneer camps she attended as a child.

“You always have to be in the group and you have to stay in the group … I can notice some of these socialist traces in Danish society,” she said, adding that the Ukrainian approach will require far more flexibility — and freedom.

For now, Tochilina is working to expand the IPC community’s knowledge about Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and she also hopes that Ukrainian students currently on scholarships in Denmark will carry back the bildung spirit and apply it toward Ukraine’s future.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?