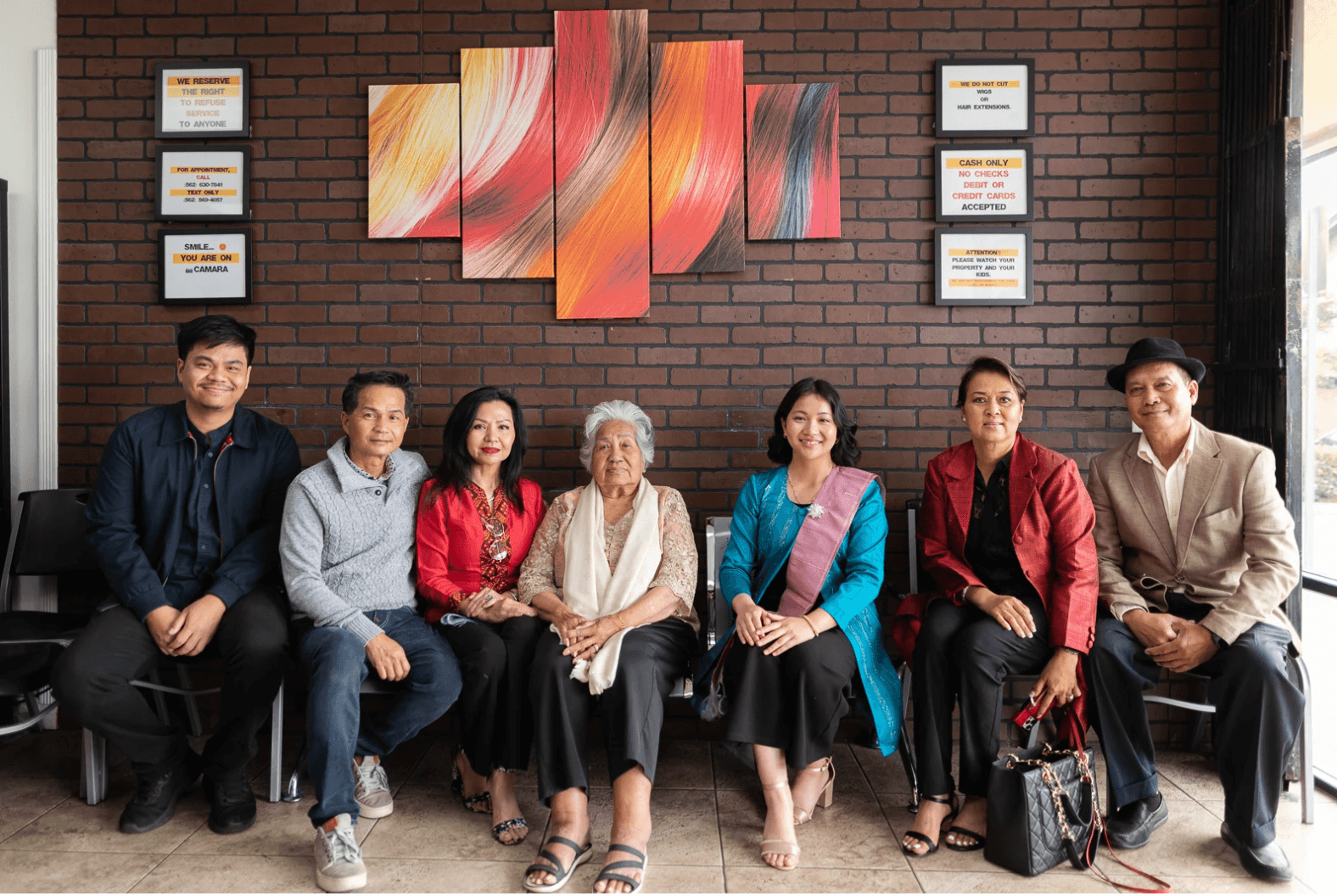

For 21-year-old Ariya Tok, the Fancy Cuts hair salon in a strip mall in North Long Beach is a sort of hyperlink to the past, present and future of her Cambodian American self.

“[My mom] renovated this entire place by hand with my dad,” she said as she sat in a salon chair while her mother curled her short hair.

Ariya Tok’s family has owned and run the salon since 1994. Her mother styles hair there and gave jobs to family members.

“She helped put everyone through college because of the salon … it’s the sole reason why my family is thriving here and why I’m able to graduate.”

On Sunday, Tok, her mother, father, brother, grandmother, aunt and uncle met at the salon at 9 in the morning for Tok to get her hair done for a very important graduation ceremony. She’s earned her bachelor’s degree in art history from California State University, Long Beach. The university ceremony took place earlier in the week, but on this day she would take part in an on-campus ceremony organized by the Cambodian Student Society (CSS).

“I feel so proud of her,” said Dannaly Tok, her mother. “She’s grown up, not a baby anymore … I feel like I’m graduating with her.”

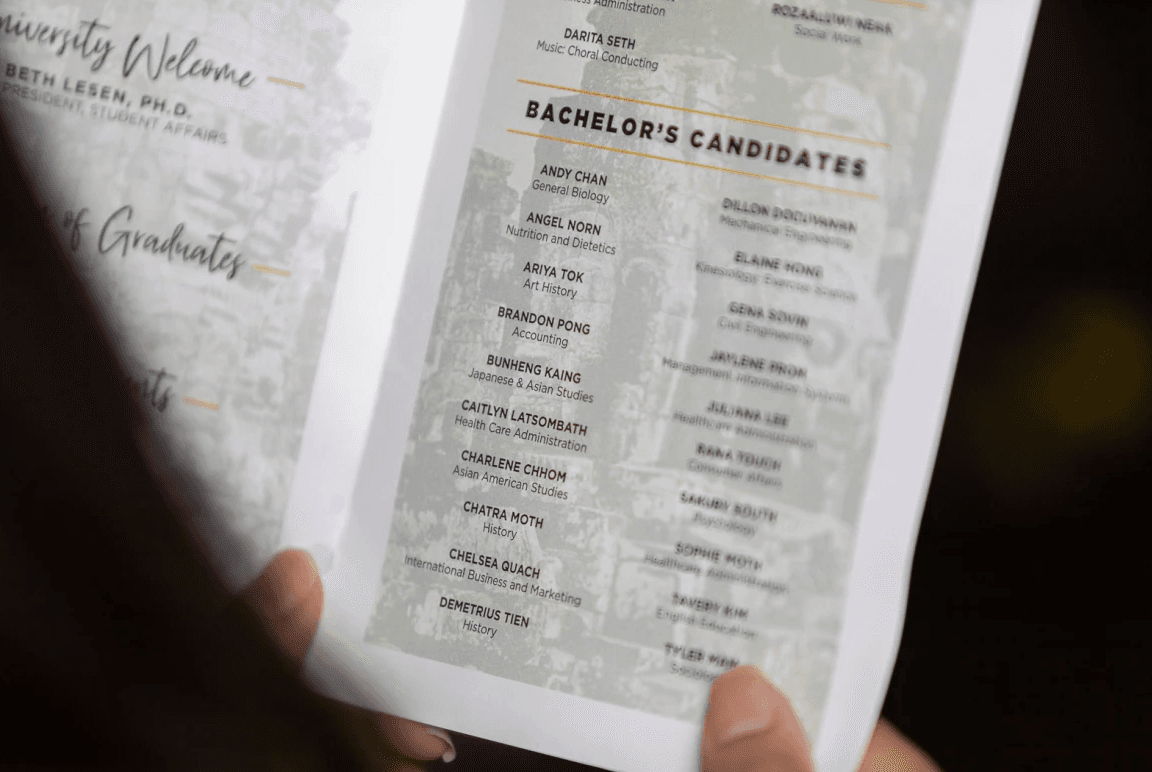

Ariya Tok is one of nearly two dozen Cambodian American graduates who took part in the Cal State Long Beach cultural ceremony, an event with special significance to the Cambodian Americans living in an area that has the largest such population in the United States.

Nearly 50 years since a genocide in their home country brought thousands of Cambodians to Long Beach and other parts of the US, people in that community say the awarding of college degrees to this third generation of Cambodian immigrants symbolizes both a response to that genocide and the strengthening of a people they hope US society will begin to see in their full scope as human beings, not just the victims of genocide.

The ancestors are in the salon

In many ways, Fancy Cuts feels like the model of a modest hair salon, with its black leather chairs, assortment of hair products, and the hanging photos of gleaming hair styles.

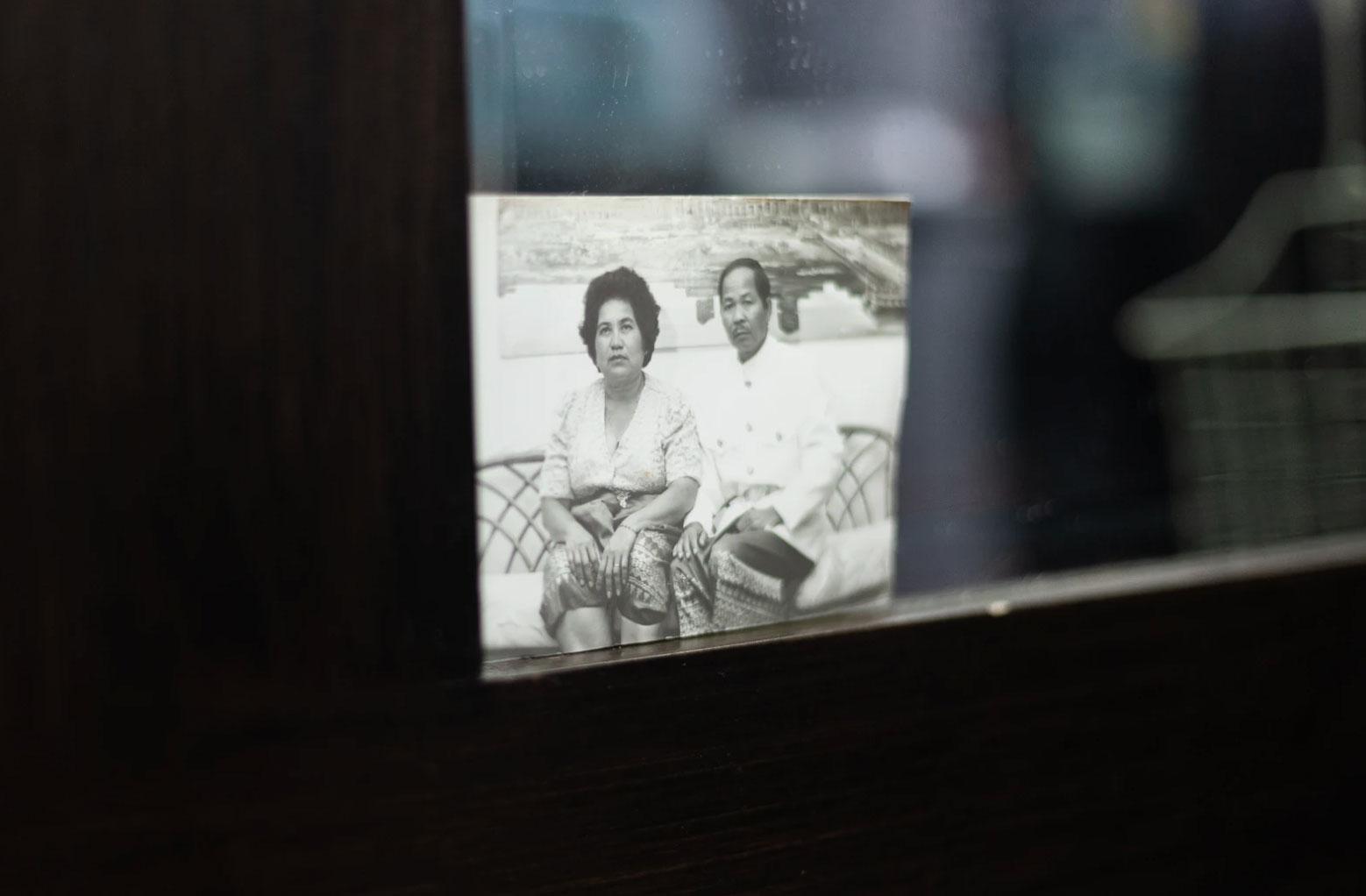

Then you notice the other touches, linking this place to a faraway land, other times, and possible futures. There’s the Buddhist altar with used incense sticks atop a hair product shelf, and black-and-white photos of people in studio portraits.

Ariya Tok’s mother keeps two framed photos near her chair. In one, a man in a white shirt and skinny black tie tilts his head in a pose like that of a Hollywood headshot. It’s Tok’s grandfather.

“He worked for the American embassy back then because he spoke seven languages,” said Dannaly Tok of her father.

He disappeared after the Khmer Rouge took over in 1975, while Dannaly Tok was a small child. She was 14 years old when she left Cambodia in 1981 with her mother.

People urged her over the years to go back and look for her father. Her eyes began to well up with tears as she said that she refused to do so.

“I don’t want to talk about it too much,” she said.

Tok said 80% of her family died in the Cambodian Genocide. Her two kids have heard her pain.

“I was the first generation to be born here,” said Matt Tok, Ariya Tok’s older brother.

“We carry a lot of weight on our shoulders to honor something that we personally didn’t experience but we hear it all the time,” he said.

Architects of genocide tried to kill off Cambodia’s educated people

The Khmer Rouge was a Maoist revolutionary group that sought to eliminate perceived Western influences and class structures within Cambodia. It sought to transform Cambodia into a wholly agrarian society. It carried out its ideology after seizing power in April 1975 by clearing cities and shipping people to the countryside. People with higher education, professionals, anyone perceived to be “educated,” were targeted for death. The Khmer Rouge murdered three million people in the ensuing genocide, one-quarter of the country’s population.

While some Cambodian students had settled in Long Beach in the 1950s and 1960s after enrolling at Cal State Long Beach, thousands arrived in the region after the Khmer Rouge took over, and even more arrived in the early 1980s after Vietnam invaded Cambodia.

People in the United States may know the rough outlines of the genocide. In Southern California, people also know the many doughnut shops popularized by Cambodian Americans.

The Pew Research Center found that just 21% of Cambodians residing or born in the U.S. have a bachelor’s degree. That’s lower than for all Americans (33%) and all Asians (54%) in the United States. Every degree has signficance.

“This is a rebirth of Cambodians,” said Leakhena Nou, a Cal State Long Beach sociology professor and the only tenured Cambodian faculty at the university.

Long Beach City College says 1,138 students of Cambodian descent enrolled this past academic year. Cal State Long Beach says 591 students of Cambodian descent were enrolled in the most recent spring semester.

“We want to prove to the world that Cambodians are more than just victims of the Khmer Rouge,” said professor Nou, who’s also the advisor to the Cambodian Student Society.

Long Beach is a ‘sacred’ space for Cambodian Americans

Long Beach is officially a sister city with Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital.

“Long Beach is a very sacred city in the history of the Cambodian people because it gave us an opportunity to survive,” said Sotheara Lim, a 2012 Cal State Long Beach graduate who works for Microsoft as a project manager.

“For Cambodian graduates … for them to … graduate and attain education is a very sacred thing because at one point in the history of our people, if you were educated, you were going to be killed,” he said.

Lim attended the Sunday graduation ceremony to give the keynote speech to about 200 people.

The speech was equal parts reminder to be grateful for the support from their families and warning of the challenges that come with being Cambodian in today’s United States. He reminded graduates that if Asian Americans are an “invisible” group that’s hardly understood by mainstream America, Cambodian Americans are even less understood.

Only about 10% of Cal State Long Beach’s Cambodian students are active in the Cambodian Student Society. The current generation is growing up without seeing positive images of themselves in popular culture.

“Before I joined CSS, I didn’t have a strong sense of our community and sometimes I felt like I didn’t know what it meant to be Khmer,” said Emily Touch, a third year student and co-president of the Cambodian Student Society this academic year.

Khmer, pronounced kuh-MY, is the word for the Cambodian language and the Cambodian people.

Touch gave the closing remarks at the ceremony. Before she congratulated the graduates and their families she shared the insight she gained from her involvement in the student group.

“It helped me realize that we all have different answers to what it feels like to be Khmer,” she said.

Carrying out the legacy of her ancestors in a different home

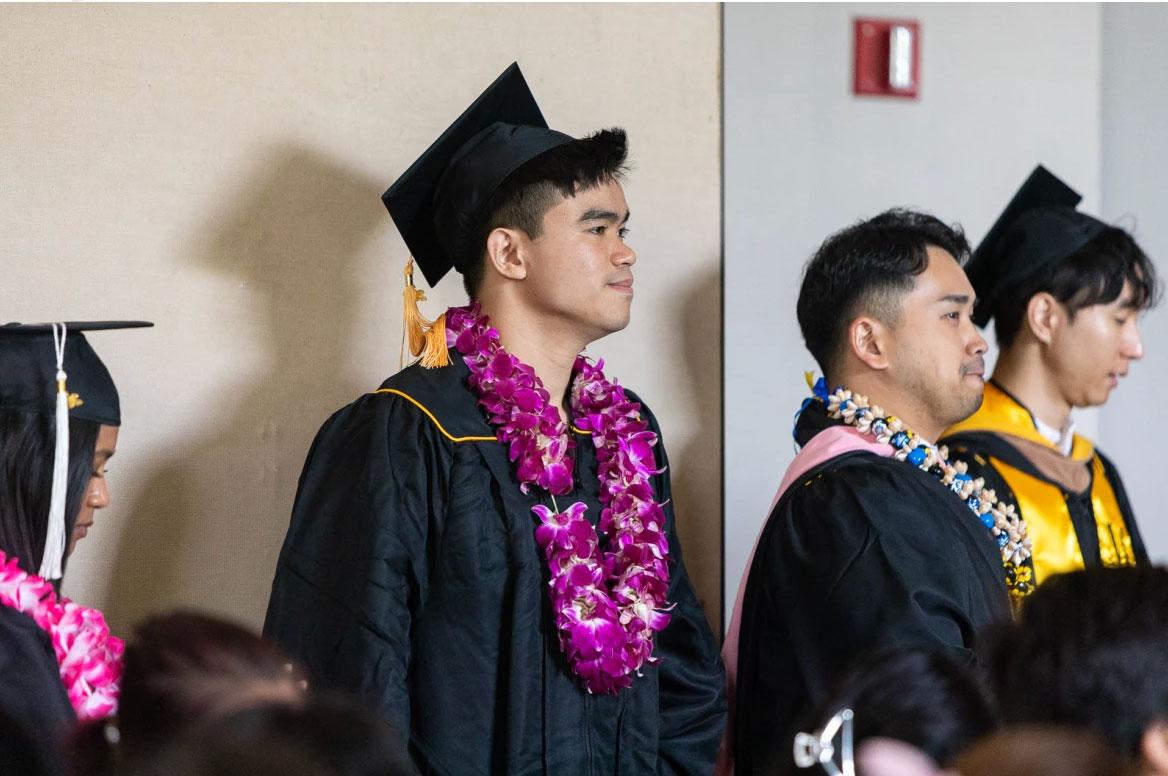

Ariya Tok was at the end of the line as graduates walked to the stage during Sunday’s ceremony. Names and majors were called, “Pomp and Circumstance” played on the PA, and each graduate held a certificate as photos were taken.

Ariya Tok majored in art history. Her goal is to have a career in US museums, and along the way help institutions do more to bring Cambodian Americans into galleries.

“Someone in our family many hundreds of years ago loved art as much as my sister,” said her brother Matt Tok, who is nine years older and has a nursing degree.

“It’s kind of a full circle thing … she’s honoring somebody in our lineage that we’ve never met before,” he said.

The feeling that he and his family are standing on the shoulders of many generations of Cambodians, he said, makes the burden of the genocide easier to hold.

An earlier version of this story was originally published by LAist.com.