The Russian novel “Summer in a Pioneer Tie” opens at an old, rundown summer camp in eastern Ukraine, where the young protagonist recalls falling in love with his camp counselor.

What starts as a summer romance between two teenage boys turns into a sprawling novel when the lovers improbably meet again as adults.

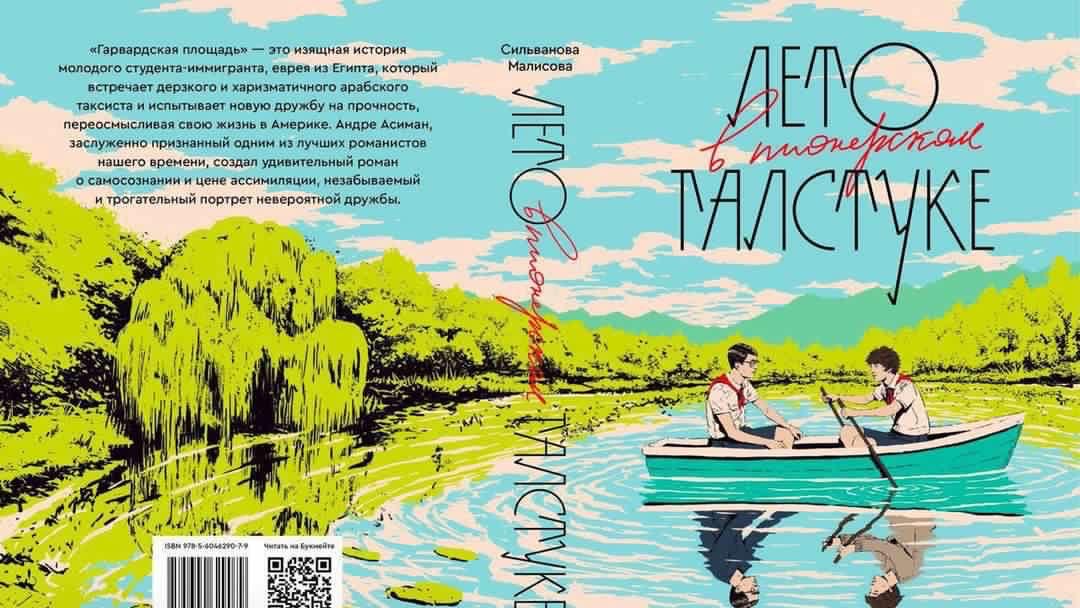

Co-authors Elena Malisova and Katerina Silvanova posted the novel for free on a Russian fan fiction website where it garnered a huge audience.

“We were really surprised by the amount of readers we had — some even got tattoos with quotes from the book,” Malisova said.

The book became so popular that a Russian publishing house specializing in young adult novels published it in print in 2021. It quickly became a bestseller, with roughly 400,000 copies scooped up by readers.

More recently, though, the novel has come under scrutiny. Russian lawmakers condemned its publisher, Popcorn Books, for violating a new law passed last December that bans any reference to LGBTQ themes in Russian society. The publishing house has become the target of the government’s first investigation into possible violations of the new law.

The law expands on a 2013 piece of legislation banning the distribution of so-called “gay propaganda” to minors. Under the new law, any mention of LGBTQ topics in popular culture, such as books or films, could result in significant fines.

“Summer in a Pioneer Tie” has been taken off of store shelves in Russia, and websites, including online book forums, have even deleted reader reviews in order to avoid running afoul of the new law.

Satenik Anastasian, the former editor-in-chief of Popcorn Books who recently resigned, said the lawmakers overreacted to the book’s content.

“There were literally, like, no sex scenes in the book,” Anastasian said.

The book also had an “18+” label in compliance with the country’s older legislation banning “gay propaganda” for minors.

Anastasian said that before the new law was passed last year, Popcorn Books specialized in queer literature, but they strove to represent a diverse catalog of writers in order to avoid the reputation as a queer-focused publishing company.

“We knew that getting labeled as a queer publisher would be very dangerous in Russia, because once you are on the radar, you would not be able to get off of it,” Anastasian said.

Malisova and Silvanova’s novel helped open the doors for other Russian authors who write about queer topics.

“Once our book came out, many publishers started approaching authors who write queer books to offer them contracts because it turned out there is a demand for them,” Silvanova said.

After their book received widespread attention in Russia, Silvanova and Malisova appeared in unflattering reports on Russian state TV, which displayed their photos. They started to receive so much harassment and threats online that the two finally left the country last year.

“I feel like the people who threatened us did everything possible to ensure I’d be afraid to stay in Russia — they deprived me of my country and separated me from my family,” Malisova said.

A defining part of Putin’s presidency

Russian President Vladimir Putin has made promoting traditional values a defining part of his presidency and has even insinuated that LGBTQ rights are connected to “satanism.”

Irina Roldugina, a historian of queer history in Russia and a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pittsburgh, said that Putin offers Russians a false version of history where gay people never had a place in Russia. But Roldugina said Putin’s message omits important historical truths: The Bolsheviks actually abolished a law against sodomy after the Russian Revolution in the early 20th century.

“Technically, Russia was the first major country to decriminalize homosexuality,” Roldugina said.

Starting under Stalin, gay men were prosecuted by the state for having relationships. Roldugina said that history, and the current situation in Russia, obscure a fundamental part of the Russian character.

“Russians are not inherently homophobic people, they just do not have information on LBGTQ+ issues because this kind of information is actually banned,” Roldugina said.

Russia’s new anti-LGBTQ law is part of a regional trend of governments repressing writers and journalists.

In neighboring Belarus, President Alexander Lukashenko’s government has closed writers’ organizations and jailed dozens of authors with the aim of stopping the development of independent literature, according to Hanna Komar, a Belarusian poet and translator who works with an initiative called Free All Words.

“They don’t want any freethinking people [in Belarus] who think critically and that’s what literature helps you do,” Komar said.

Komar, who published a book of poetry about the 2020 protest movement in Belarus against Lukashenko, has also left her home country and worries that she could be targeted by the government if she returns.

Still, there’s been significant demand for books like “Summer in a Pioneer Tie.”

“Many readers who aren’t part of the LGBTQ+ community wrote to us saying that seeing the world through the eyes of a queer person changed their opinions and widened their perspectives,” Malisova said.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?