‘The Stolen Daughters of Chibok’: the impact of the abduction of Nigerian schoolgirls 9 years on

Nine years ago, disturbing news from West Africa gripped the attention of the globe. It was when as many as 276 schoolgirls and young women were kidnapped by members of the Boko Haram militia in the town of Chibok in northern Nigeria.

When the heavily armed men came into the government’s boarding school in search of food, they found the girls aged 14 to 21 — who, at the time, were taking exams — and abducted them. Militiamen forced them to get onto a truck for a three-day journey to the Boko Haram enclave in the Sambisa Forest.

In the process, about 57 girls managed to escape. A grim total of 219 young girls were finally held hostage.

When the news came out, there was a lot of denial and blaming from local politicians, which in the long term was detrimental for the girls, recounted Aisha Muhammed-Oyebode, human rights activist and founder and CEO of the Murtala Muhammed Foundation.

“It took them three days to get to Sambisa Forest, but because there was so much denial and there was a lot of politicking around that time because it was around elections, nobody was really paying a lot of attention,” she said. “A lot could have been done to rescue those girls if we had reacted immediately. And, I think, that was what made it even more tragic for all of us.”

What followed was years of captivity and sexual exploitation for the girls at the hands of Boko Haram and heartache for their families. It took years for the government to negotiate a release. Many girls still remain unaccounted for.

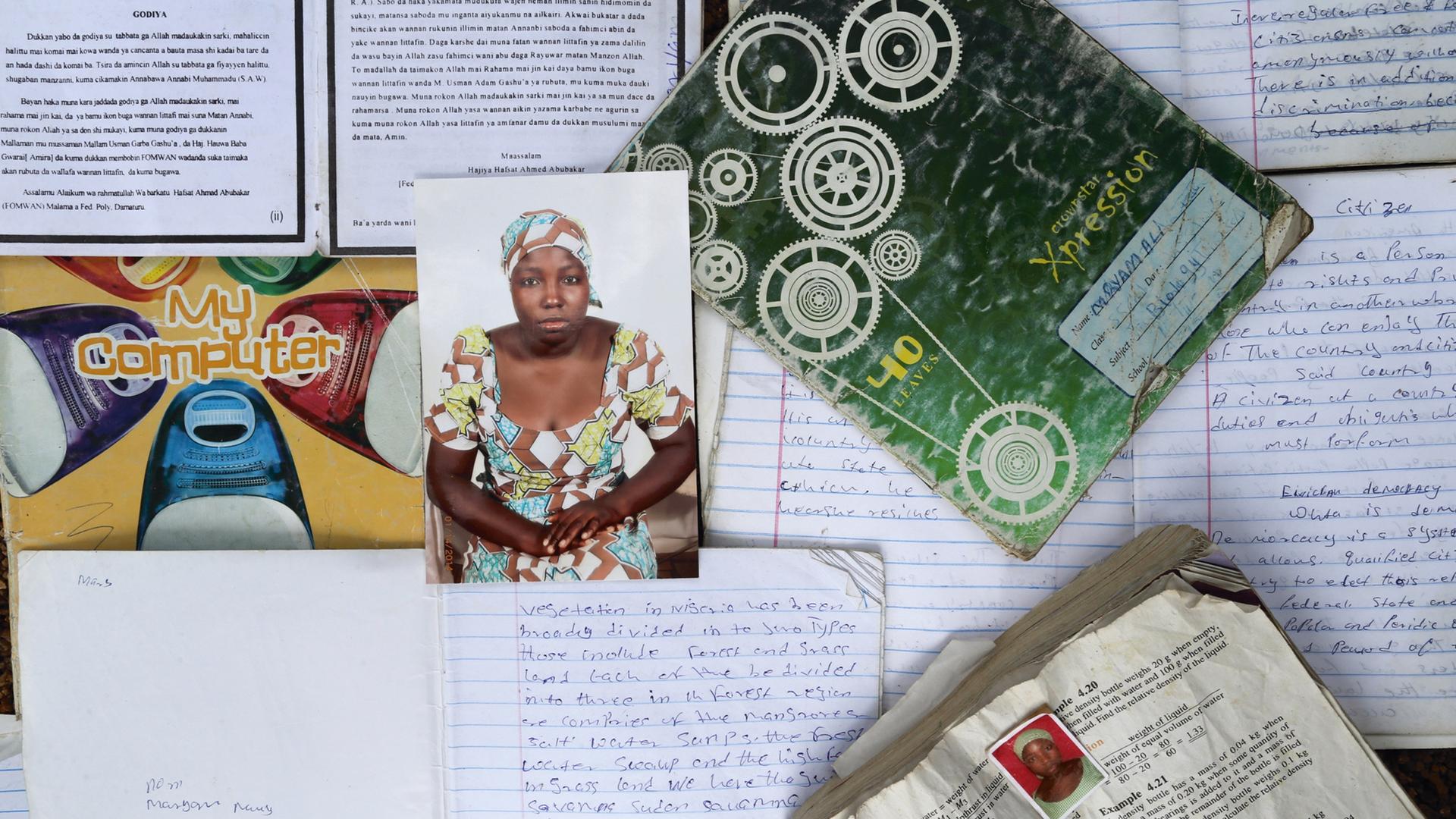

Muhammed-Oyebode met some of the Chibok families in the years that followed the abductions. In her recent book “The Stolen Daughters of Chibok,” she presents a collection of powerful portraits, photographs and poignant essays, many by the mothers and fathers of the Chibok students, recounting the tragic impact of the abductions in their rural homes and communities.

“In that community, especially, they were particularly invested in their daughters going to school. These girls, most of them were in the final years of their schooling. They were actually almost done with getting ready for university, so it was really devastating for them,” Muhammed-Oyebode said.

Some of the girls who returned or were released went back to school. Nearly a hundred families have been totally bereft. “We now know from the stories that have come out that we have lost at least one-third of those girls,” Muhammed-Oyebode said. “But the families don’t know which ones. So, the parents can’t even grieve their deaths.”

Organizations in Chibok are working to educate people, helping them embrace those who returned, some of them pregnant or with the children they bore in captivity. Still, Muhammed-Oyebode says there is a stigma associated with the sexual exploitation the girls endured.

“I think it’s going to take a lot of education for people to begin to realize that these things have happened through no fault of these girls,” she said. “And we actually have a greater responsibility because they were taken under our watch.”

Muhammed-Oyebode’s book, “The Stolen Daughters of Chibok,” with photography by Akintunde Akinleye, was published in the United States by powerHouse Books.

Listen to the full interview of Aisha Muhammed-Oyebode with The World’s host Marco Werman by clicking the audio player above.