Panamanians remember 1989 US invasion and continue to demand justice and accountability

In the poor Panama City neighborhood of El Chorrillo, the wounds of the 1989 US invasion are still written on the walls.

“Do you see this? This remains as a memory of the shots fired,” El Chorrillo resident Efrain Guerrero said. He points to the bullet hole left in the wall from the invasion, down the street from his house. Guerrero has dedicated recent years to telling the story of El Chorrillo’s past.

“Right here. There was a downed helicopter,” he said.

Overnight on Dec. 20, 1989, nearly 30,000 US soldiers attacked positions across Panama. The neighborhood of El Chorrillo was ground zero.

One video, shot by a US soldier during the invasion, shows flames engulfing homes as planes and helicopters fly overhead. El Chorrillo surrounded the main military barracks for the Panama Defense Forces. When US soldiers attacked, they leveled entire city blocks.

University of Panama professor Olmedo Beluche wrote one of the first books about the invasion and its toll. He said 20,000 people lost their homes.

“It looked like Gaza today,” he said. “Officially, 560 were killed. There may have been a few more. The Red Cross saw 2,000 people wounded.”

Resident Omar Gonzalez today holds youth activities in a park where the Panamanian military barracks once stood. He said he was 12 years old the day the US invaded. His family had decorated their Christmas tree earlier that day.

“We watched out the window, and we could see the bombing,” he said. “The wooden houses on this side of the barracks lit on fire, and we watched several innocent people die there.”

Many were buried in mass graves.

US troops captured Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega and took him back to the United States, where he was imprisoned on drug trafficking charges. Then the US installed a puppet government in Panama.

Noriega was a polarizing figure.

Many Panamanians celebrated his removal. Earlier that year, he had refused to recognize elections that would have removed him from power.

But the invasion was different story.

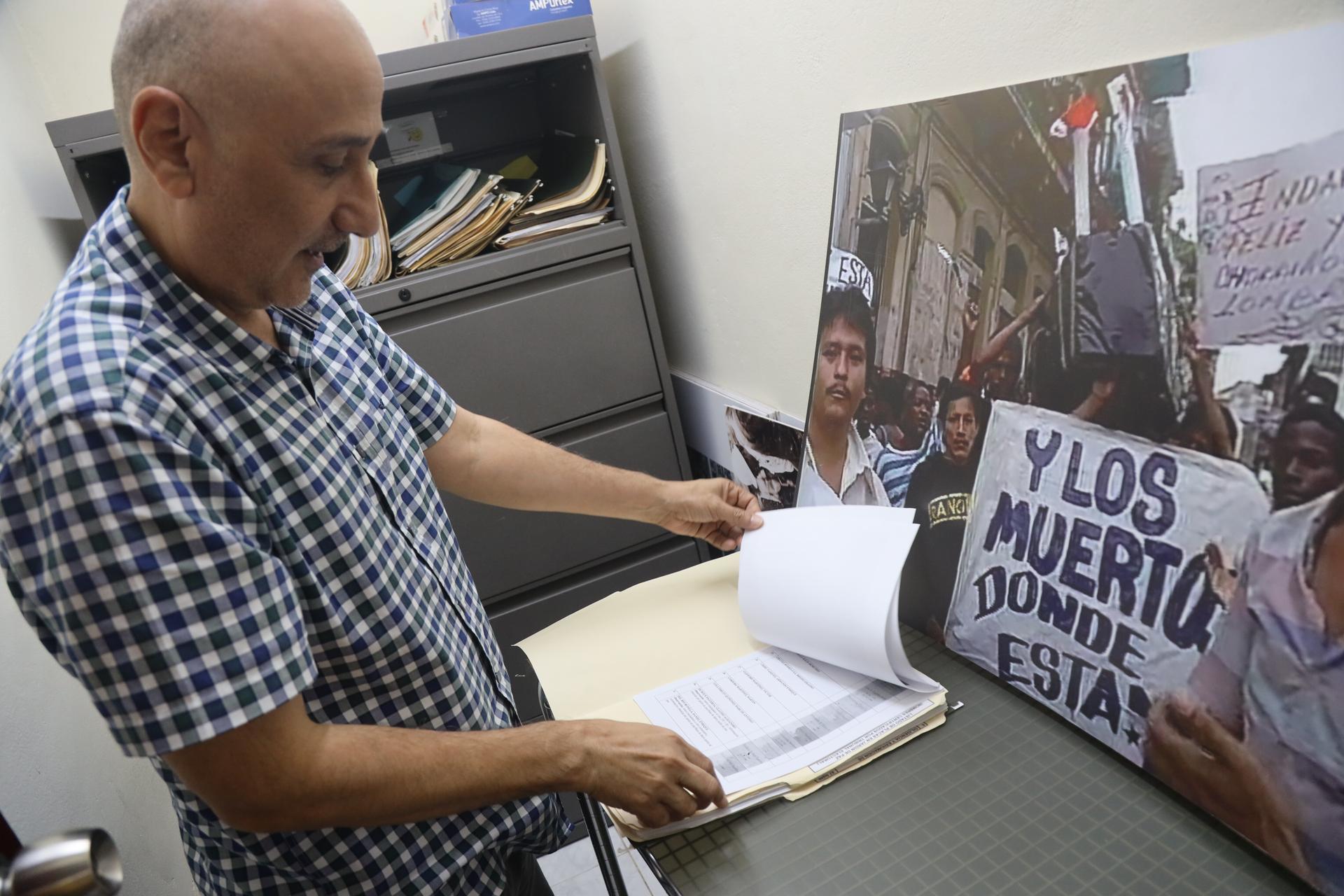

Since 2016, the Dec. 20 Commission has been charged with identifying and confirming the dead and disappeared. José Luis Sosa overseas the commission. He goes through the archives — rows of files on the invasion and the victims.

The World asked him why it took the Panamanian government 27 years to launch a commission to investigate the invasion and its aftermath.

“I have always felt that there was a certain fear of bothering the United States with an investigation into the invasion,” he said. “Fortunately, we’ve matured, and we have made progress.”

But his is not the only investigation. Only months after the US attack, young lawyer Gilma Camargo launched a case against the United States before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. It took nearly three decades, but in 2018, that commission finally ruled that the US was responsible.

“The decision is marvelous because it recognizes this territorial responsibility of the US,” Camargo said. “It gives compensation, monetary compensation, for deaths and injuries, for food, for vehicles, and I keep on saying from the first dead man to the last plate they broke in Panama is covered.”

The ruling set a precedent. It was the first time victims from one country had brought the government of another before the commission and won. But the decision was non-binding. In other words, the United States has ignored it and not paid a dime.

Panamanians say they cannot just ignore the past.

Camargo said the invasion destroyed the country, and its legacy is still felt today.

“It’s everything that we live in now … the corruption, the weakened institutions, the financial mess that we are in with people not getting paid well and not getting healthcare,” she said.

Marches are held yearly on Dec. 20 to remember the victims and demand justice.

Pedro Silva is one of the march organizers. He’s a filmmaker who was 8 years old when the US bombs fell.

“We survived the invasion. But others died,” he said. “Our work is important so that when you meet someone who didn’t experience the invasion, you can say with clarity that this was an act of cruelty, an act of war. We cannot let this be forgotten.”

Last year, Panama finally declared Dec. 20 an annual day of national mourning. It doesn’t change history or bring back the dead, but it’s a sign of the country’s slow steps toward honoring the victims and ensuring that the past is not forgotten.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!