Dozens of students from Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar sat on the floor reviewing some 200,000 documents that were set on fire during violent protests a few weeks ago.

They went through every file and every paper that could be salvaged.

“We are trying to see if these documents are totally destroyed or if they can be saved using some archival techniques,” said Abdulai Ba, a student of archival science at the School of Literature and Social Science. He said that the whole thing was sad.

Piles of documents lined the floor, including registration forms, academic records and other documents. It was unclear if they had any digital backup.

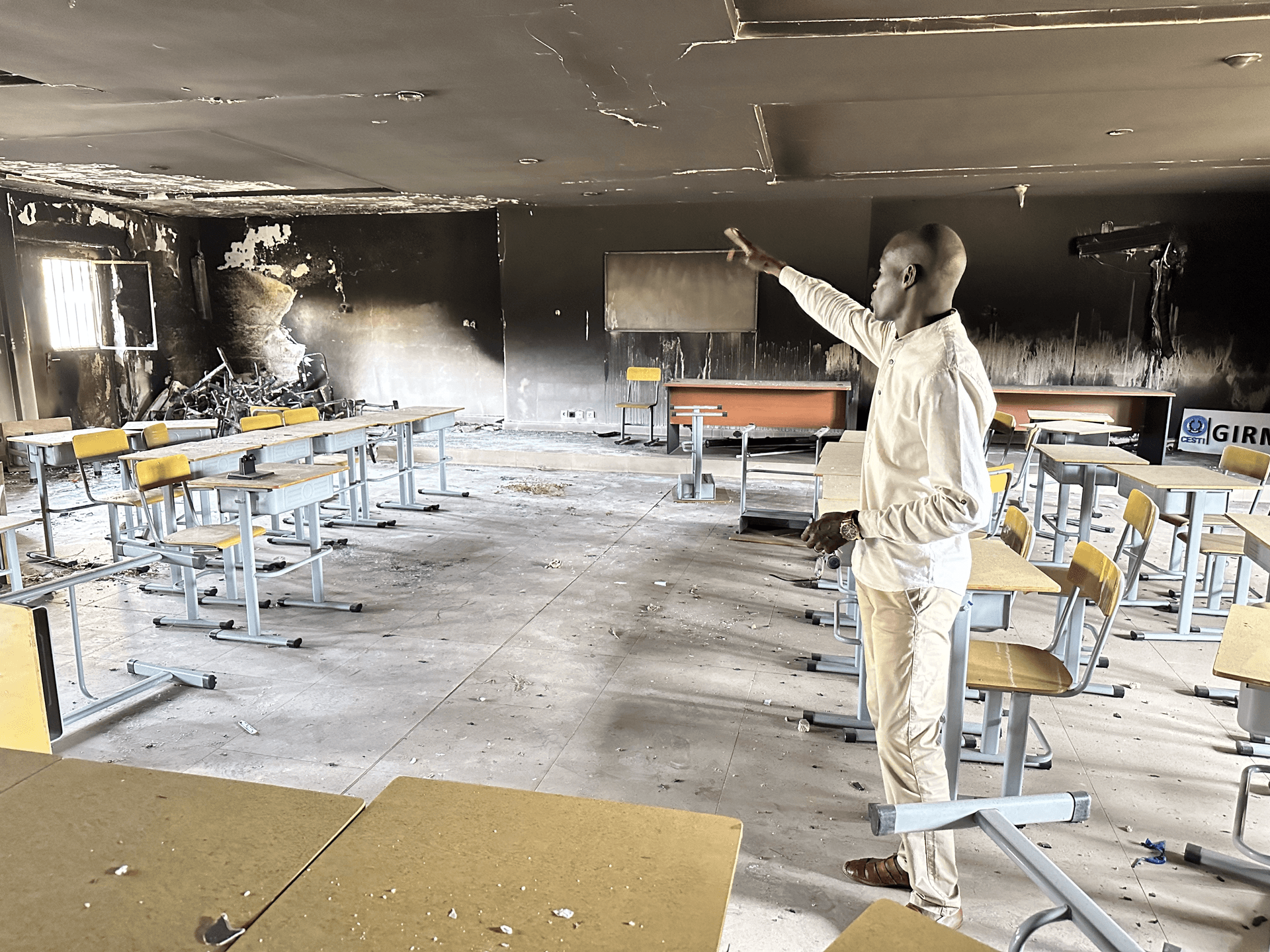

At the nearby journalism school, Mouminy Camara, a researcher at the Center for Information, Science and Technology Studies, presented one of the classrooms that were set on fire. Chairs and desks were thrown around, and the walls and floors were charred.

“It’s a shame,” Camara said. “We can’t understand why this happened because they ransacked everything. At the moment, we are in the process of quantifying the material damage. It will be huge.”

After the fire, the university closed and students had to vacate the dorms and start taking online classes. Camara said that it’s problematic because not all students have access to a computer or the internet at home.

People in Senegal are still trying to make sense of the deadly riots that took place at the beginning of June when clashes between the police and supporters of leading opposition figure Ousmane Sonko left 16 people dead. Most of them were under the age of 30.

Families of several victims learned that their loved ones had died from gunshot wounds, and they suspect it was the police who were firing on demonstrators.

Sonko has long been considered the greatest political threat to Senegal’s ruling party in next year’s presidential election. He was sentenced to two years in prison for “corrupting youth,” while being cleared of other charges, including raping a woman who worked at a massage parlor and making death threats against her.

The two-year sentence means Sonko won’t be able to participate in the next presidential election scheduled for February 2024.

Authorities have said that Sonko can request a retrial once imprisoned. An arrest warrant hasn’t yet been issued, and it’s unclear when he might be taken into custody.

President Macky Sall has suggested that he might run for a third term next February, which would go against the Senegalese Constitution.

The West African country is often seen as a model of political stability in the region. But that perception is changing.

“Since early 2021, the political crisis in Senegal has worsened month after month,” said Guillaume Soto-Mayor, an expert on West Africa with the Middle East Institute.

“The civic space has [shrunk], journalists have been imprisoned, a number of civil society figures have been imprisoned.”

“The civic space has [shrunk], journalists have been imprisoned, a number of civil society figures have been imprisoned. A number of political opponents have been imprisoned, and a lot of intimidation or violent action has occurred since then.”

The president has been criticized for systemic corruption and high unemployment rates for the young people who are leading the fight against him.

There have been several violent protests in the past couple of years, often including children who appear to be under 10 years old.

The most recent demonstration occurred in several parts of the city, including Ngor, a poor neighborhood in Dakar.

“The whole village was out. And I went out to fight for the village. All they wanted was just a high school [to be built in the village], and the authorities said no,” said 19-year-old Netanya, a woman who lives in Ngor and spoke to The World through an interpreter.

There isn’t a single high school in Ngor, and students must travel to a different community to further their education.

Seydina Ndiaye, who runs a youth development program in Dakar, said many young people are fed-up with politicians.

“None of them [are] talking about youth policy. None of them [are] talking about youth access to healthcare. None of them [are] talking about youth aspiration. None of them [are] having a youth political plan,” Ndiaye said.

He added that politicians are trying to pit young people against their opponents by encouraging them to turn out for protests.

“I think it’s not fair to use the kids just to reach the power. Why the youth are not [at] school? I think that’s [the] kind of the question that we need to ask,” Ndiaye said.

For the moment, the streets are calm in Dakar. But with political tensions high, and young people increasingly frustrated, the unrest could soon return.

Related: Sierra Leone elections: Familiar faces vie for voter trust as economy stagnates

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!