A game of numbers: How air defense systems work and why Ukraine is eager for more protection

Israel’s Iron Dome air defense system is the gold standard for defending against missiles and rockets.

Ukraine has received a broad array of military supplies from the US and other allies. Recently, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy made an urgent plea specifically for additional air defense resources from the West in response to increased air attacks by Russia.

To understand Zelenskiy’s emphasis on air defense, it’s important to look at the types of air weapons that Ukraine faces and how air defenses work to counteract those threats. It’s also important to understand why this type of warfare is all about the number of assets each side has at its disposal.

Increased air attacks

On Oct. 10, 2022, Russia launched a large barrage of airborne weapons against a variety of targets in Ukraine. The types of weapons involved in the attack included short-range ballistic missiles and cruise missiles.

Ballistic missiles are accelerated by rockets from the ground or from aircraft, tend to follow a predictable path and are somewhat easier to track. Cruise missiles carry a propulsion system that allows them to maintain speed and fly more unpredictable flight paths, including trajectories that are close to the ground. They are much more difficult to detect, track and shoot down.

Then, on Oct. 17, Russia launched a barrage of explosive drones at Ukraine’s capital city, Kyiv. Explosive drones, known as loitering munitions, tend to be small weapons that are difficult to defend against. By circling overhead, they are able to surveil a region of interest, gathering information before identifying a specific target to attack. Russia has acquired explosive drones from Iran, according to US officials.

Air defense systems

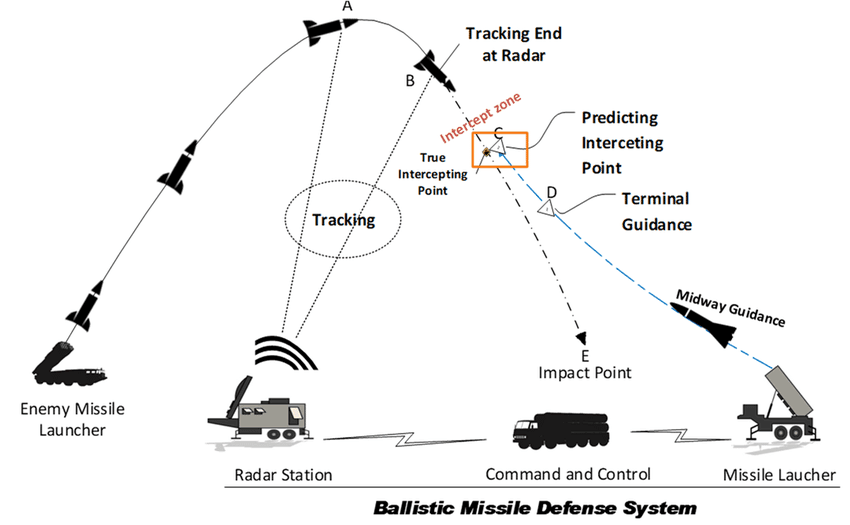

The defense against all such air threats involves an integrated system of several elements.

Early warning radars located at Ukraine’s borders first detect the approach of missiles. These weapons are further tracked along their flight trajectories by a dispersed network of additional radars. The primary defensive countermeasure against ballistic and cruise missiles involves surface-to-air missiles (SAMs): You destroy a missile using a missile. This is no easy feat because the SAM must track, home in on and hit a high-speed target that may be changing direction.

In the US, key strategic assets such as the White House are protected against aerial attack by the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS). NASAMS was designed to counteract a variety of incoming threats, including cruise missiles, aircraft and drones. Each NASAMS contains 12 interceptor SAMs. No information is available publicly on its effectiveness. NASAMS is one of the options being considered by the US to help support Ukraine.

Another notable example of an air defense system is the Israeli Iron Dome. The system is designed to defend against rockets and artillery shells launched from up to 155 miles (250 kilometers) away. Each Iron Dome missile battery consists of three to four missile launchers, each with up to 20 interceptor SAMs.

The system is reported to have a 90% kill rate for rockets launched against Israel. Veteran national security correspondent Mark Thompson described Iron Dome as possibly the most effective missile defense system the world has seen.

Both NASAMS and Iron Dome are reported to be effective against drones. However, SAMs are an expensive way to defend against such low-cost targets, and they could be overwhelmed by large numbers of drones. Directed energy weapons such as high energy lasers are being developed and deployed to provide a potentially more cost-effective approach to neutralizing low-cost drones.

A numbers game

The significance of the plea by Zelenskiy for additional air defense systems can be understood in the context of a numbers game. Different air defense systems have a range of effectiveness against different aerial threats. However, none of the defense systems is 100% effective.

Moreover, an adversary can significantly reduce the effectiveness of air defense by launching salvos of multiple weapons simultaneously. Therefore, an attacker can always overwhelm a defender if the attacker has more attack missiles than the defender has defensive missiles. Conversely, a sufficient number of defensive systems may cause an attacker to stop firing altogether. It becomes a war of attrition, with the winner being the side with the most missiles.

Ukraine likely has sufficient air defenses to protect strategic military targets such as command and control centers and ammunition dumps. They do not have coverage of many other key assets such as transportation hubs and power and water facilities, the types of targets Russian forces have been targeting in recent days.

Should the West agree to provide significant numbers of air defense systems to Ukraine, it could significantly change the course of the conflict. At some point, Russia will have to confront the finite depth of its missile stockpile. The number of remaining Russian high-precision missiles is already reported to be running low.

Without the ability to wear down and demoralize Ukraine through airstrikes, Russia would be faced with the much more daunting and drawn-out prospect of relying solely on ground forces to grind out its objectives.![]()

Iain Boyd is a professor of Aerospace Engineering Sciences at University of Colorado Boulder.

This article is republished from The Conversation, an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to sharing the knowledge of scholars with the public, under a Creative Commons license.