When Boris Dralyuk was 8, his family moved from the southern port city of Odesa, Ukraine, to the Pacific shores of Los Angeles.

At first, he wanted to assimilate as quickly as possible. But it didn’t take long for him to want to reconnect with his family roots.

So, before he was even a teenager, he started reading, writing and translating poetry from Russian into English.

“I felt that the work that I was translating, even at a very young age, was really my work, every English word was a word that I had chosen,” he said, adding, “I felt a great pride in it.”

These days, Dralyuk, a writer based in LA, translates poetry and literature from both Russian and Ukrainian into English.

Dralyuk said that this has become even more important since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Some publishers are scrambling while Ukrainian literary translators are working in overdrive — because the war is driving demand for Ukrainian publications.

“I’m contacted every day by an author or a publication asking for a new translation. … It’s been really incessant, it’s also been extremely encouraging.”

“I’m contacted every day by an author or a publication asking for a new translation, asking to consult about translators, it’s been really incessant, it’s also been extremely encouraging.”

Dralyuk defines it as an art of expression, but also diplomacy.

“So, I feel that you’re using all of the resources at hand as a writer, all of the talent you have as a writer, but you’re also serving as a diplomat, as an ambassador for this foreign text, for the culture that it represents.”

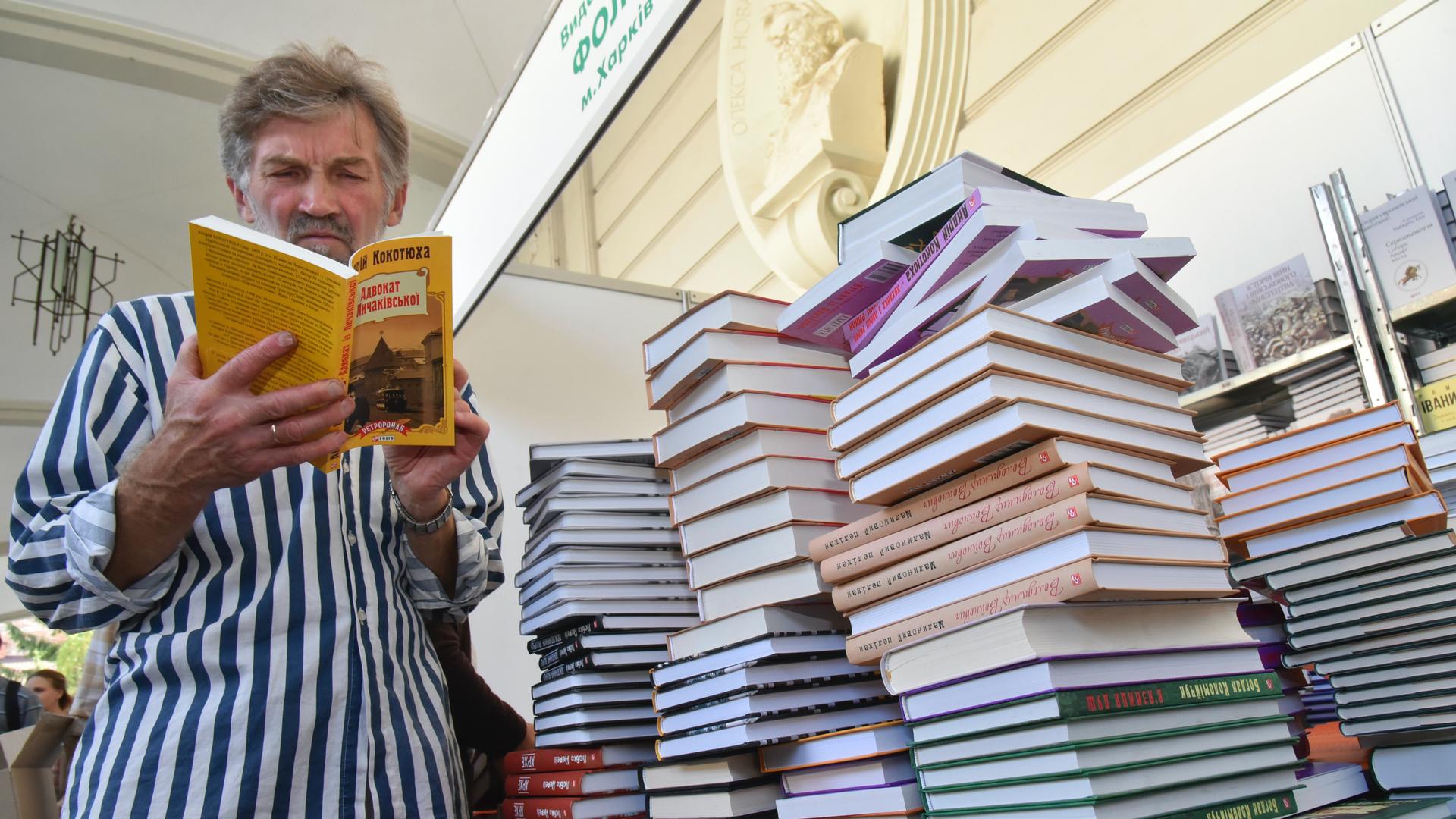

Paulina Lavrova, the director and owner of Laurus, a Kyiv-based publishing house, said that book orders are up right now.

Many people in Ukraine are displaced and out of work, and so, they’re looking for a distraction — and they’re turning to books, she said.

For years, a lot of books in Ukraine were printed in Russia, but now, she said, many Ukrainians refuse to buy books published there; they want to buy Ukrainian ones.

Lavrova said that publishing houses in Ukraine are struggling to keep up with demand; the supply chain is in shambles. Some printing houses were destroyed by Russian missiles; paper costs are way up; and writers, editors and translators are often just trying to get by.

Ukrainian publishing houses outside of Ukraine are experiencing the rush, too.

Zenia Tompkins is a literary translator with a nonprofit called TAULT, The Tompkins Agency for Ukrainian Literature in Translation.

“I’m not accepting any book projects before 2024 at this point personally, you know, I think the stronger translators are in similar positions.”

Although publishers are trying to speed up the process, it takes a long time to properly translate a book — and money.

“You know, on our end, in the last year, we’ve had two translators quit part-time jobs, to be able to translate full time.”

But it wasn’t that long ago, she said, when publishers were not so interested.

“It does feel like, for some reason, the world wasn’t noticing Ukraine as a cultural country; I [didn’t] really process this until recent weeks, that I think Ukraine was just dismissed as these backwaters of Russia.”

Tompkins, who grew up in a Ukrainian diaspora community in New Jersey, has gotten close with people from Ukraine’s literary scene.

For her, translations are not just about doing business.

“That’s what keeps me motivated to translate, is the satisfaction of those personal relationships, and knowing that I’m taking the work of someone I very much admire and respect and giving them a bigger stage to stand on,” she said. “So, it’s not this weird abstract mission; it’s very much, I’m doing this for my friends at this point, and I’m doing this for some of the most important people in my life.”