Afghan women who escaped Taliban takeover continue their education at a Wisconsin university

Last August, about 150 students from the Asian University for Women were evacuated from Afghanistan as the Taliban took over.

After a few months at Fort McCoy in Wisconsin, the women were sent to universities around the US to continue their education. Eight of the women are here in Milwaukee, studying in the Intensive English Program at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

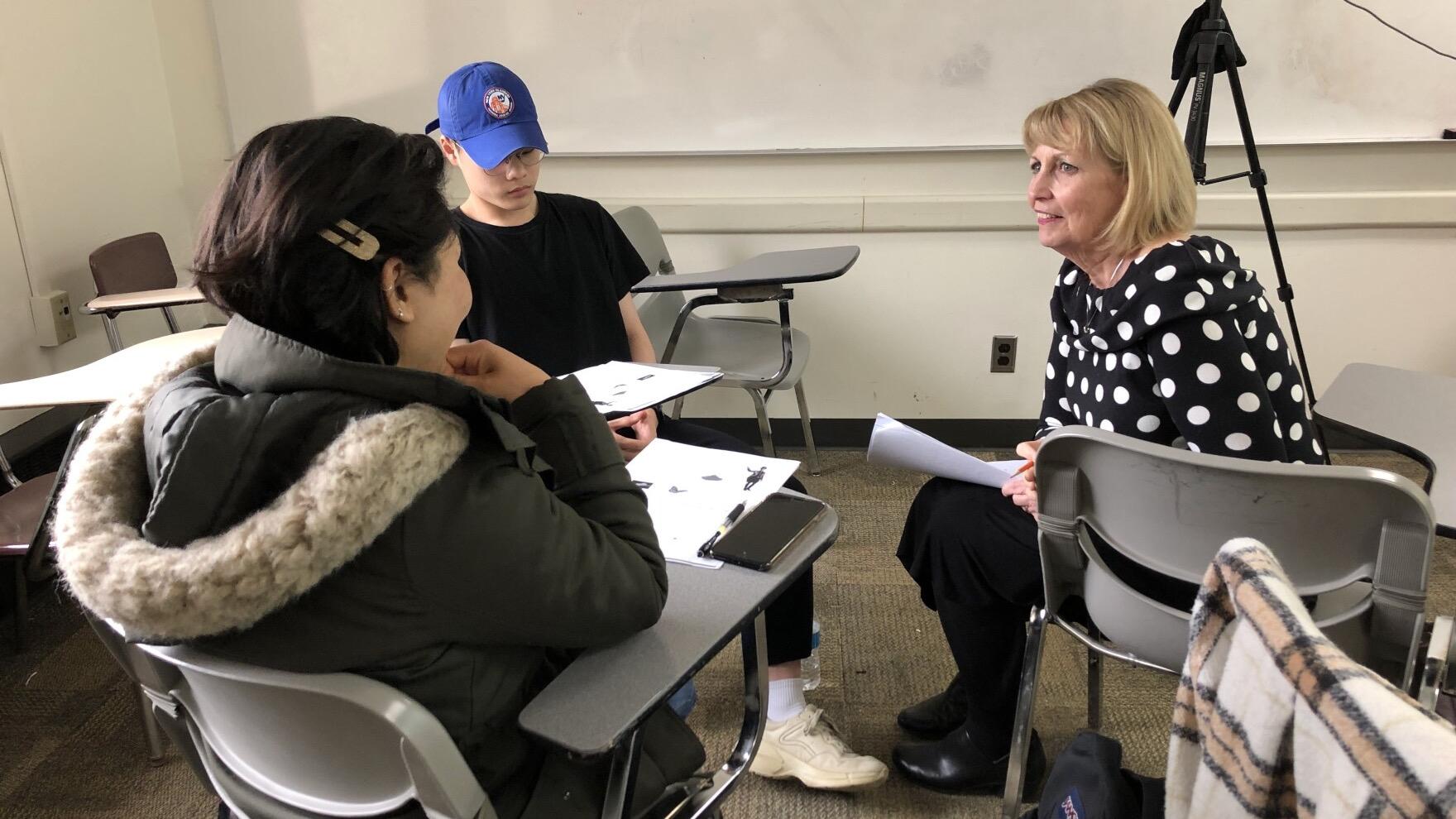

On a recent afternoon, five of the Afghan refugees were working on their vowel sounds with English instructor Jennifer Mattson.

The students seem upbeat and chatty. But these young women are still reeling at how much their lives have changed.

“It is not easy to just build a new life for yourself,” 20-year-old Mahrukh said. “I know we have to start to build a new life, but still, we have lots of concerns.”

WUWM is only publishing the students’ first names to protect their families in Afghanistan.

The students were able to escape Kabul because of the efforts of their school, the Asian University for Women in Bangladesh, which was holding remote classes for the students living in Kabul during the coronavirus pandemic.

It was a harrowing few days as the students tried multiple times to enter the Kabul airport, which was flooded with people trying to flee. They say during one of the escape attempts, a Taliban guard fired shots into the ground in front of them. Farzana, 21, said that she almost gave up hope.

“I didn’t believe, I just said, ‘That’s it, it’s over,'” she recalled. “I cannot make it. I will be like my mom, just spend all of my life inside the home and be invisible.”

Farzana said that during the final escape attempt, which was successful, she had to leave her home with just 15 minutes notice. Her mother wasn’t there, so she couldn’t say goodbye.

“I called her and said, ‘I’m going to leave again — I’m going to try again.’ So, it was very sad for me. I didn’t get to say goodbye,” she said.

According to Humans Rights Watch, the Taliban government has restricted girls’ education since coming to power, and millions of Afghan people are facing severe food insecurity.

The students say leaving their families behind was the hardest thing they’ve ever done. But 21-year-old Tahera said it was their only choice.

“We lost everything we had in Afghanistan, but we had to fight for our rights,” she said. “We want to continue our education, we want to continue our life. If we had stayed in Afghanistan, it was really hard for [all] girls.”

Now, they are continuing their education in Milwaukee. UWM got involved because of its Intensive English Program, which prepares international students to earn a degree at an English-speaking university.

English Language Academy director Brooke Haley said that UWM was eager to help.

“This is the first time that UWM has taken in refugees like this,” Haley said. “And when we first had the ask, it was a five-year full scholarship — up to a year of language study and then up to four years of undergraduate study.”

UWM couldn’t provide that level of financial support, but it did discount the English program by 40%, which is now the official refugee rate, Haley said. The rest of the tuition costs are coming from Eastbrook Church, which is also providing host families for the students.

“It’s a great example of a public university working with private, even religious organizations in the community for a common goal — to support people who need it,” Haley said. “I think it’s kind of a beautiful model.”

Eastbrook is fundraising for the first year of the students’ undergraduate studies at UWM, which they’ll start in fall after completing the English program. Once their immigration status is settled, they’ll be able to apply for federal financial aid.

Before, the students say they had five-year full scholarships at the Asian University for Women. Farzana says she worries about being able to afford a four-year degree at UWM.

“I’m very thankful of the people here and everyone that are supporting us,” Farzana said. “But I’m just saying, we have very stressful life. We have many stresses, many things to think about, and then this is also one of the things we have to think about.”

Mahrukh used a metaphor to describe it, saying it’s like carrying stones. One stone is worrying about their family, another is worrying about their country. Adding a third stone — the uncertainty about their own futures — won’t break them.

“It can’t change the girls who studied, who have a dream from Afghanistan,” she said. “We are that much strong to start a new journey in a different country.”

They still have dreams, even though leaving Afghanistan has altered them. Mahrukh wants to work for Doctors Without Borders. Farzana wants to be an advocate for refugees who have no say in the wars that displace them. She wants to help people like herself and her friends.

This story was originally published by WUWM.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?