This Afghan female fighter fought with US troops. Now, she’s readjusting to life in the US.

When the taxi abruptly stopped in traffic, the 25-year-old woman tried not to look at the heavily armed Taliban soldier who approached the passenger window of the car they prayed would carry them to a new life.

As the soldier questioned her 18-year-old nephew, she kept her gaze down, only sneaking a nervous glance at her mother and toddler son, who were squeezed into the backseat of the taxi next to her. She was terrified they wouldn’t make it to the Kabul International Airport by sunrise, terrified they’d miss their flight to safety, and terrified that if these men figured out who she was, they’d all pay a brutal price for her choices.

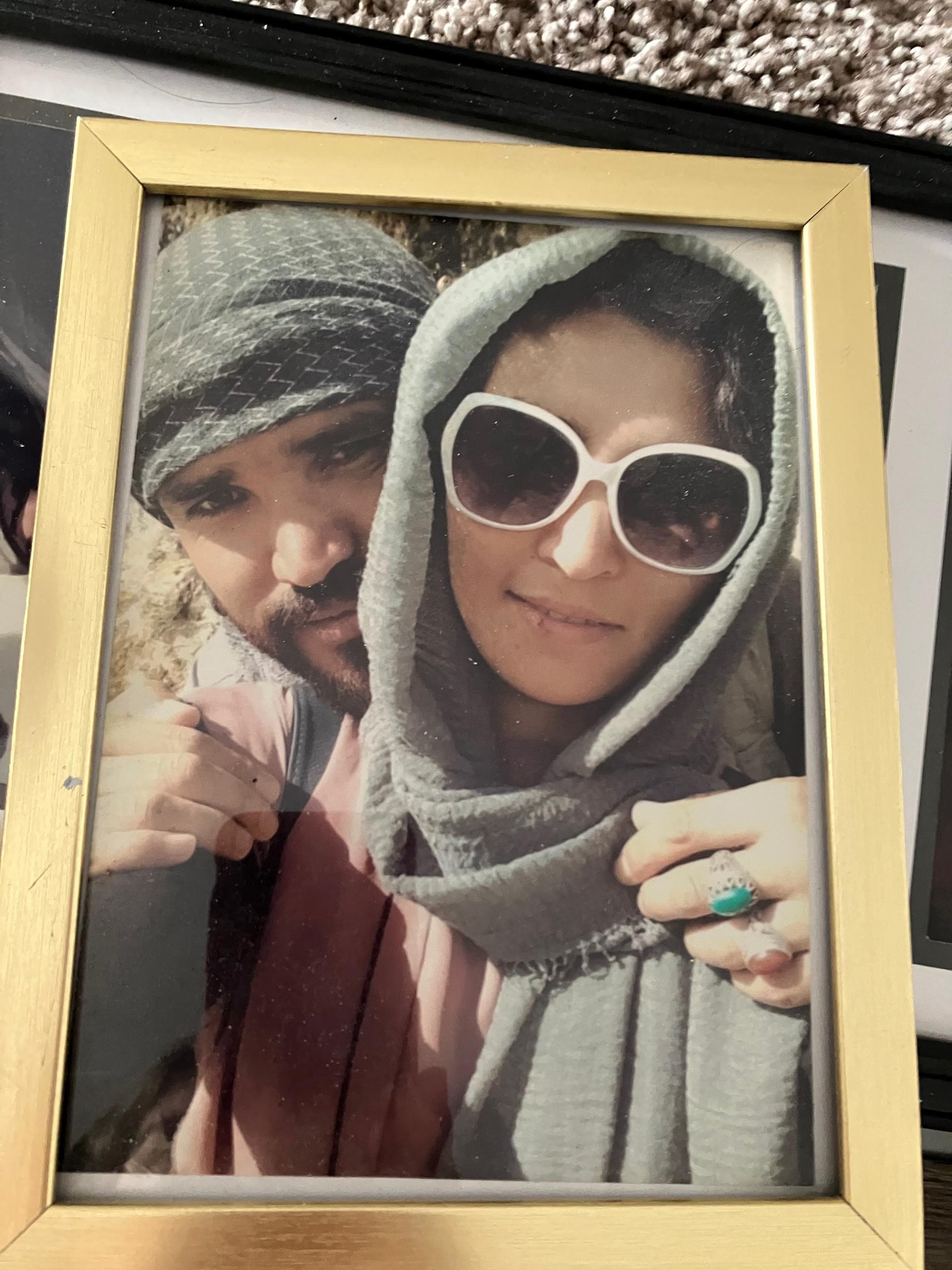

This woman, whose face was partially concealed with a head scarf, was an elite soldier working with the US Army’s Special Forces. Raised in a country where women and girls risk being killed just for going to school, she was a special operator who rappelled out of helicopters, carried an M4 carbine and actively fought to undermine the Taliban.

As the US withdrew the last of its military forces in August of 2021, this woman, and thousands like her, had no choice but to abandon their homes or risk prison or death for helping the Americans during the two-decade war.

Her name is Sima. She does not use her last name because she fears what the Taliban might do to the members of her family who still live in Afghanistan. She proudly served in the Afghan army for six years, part of an elite unit called the Female Tactical Platoon that assisted on combat missions and night raids with the US Army Special Forces, though she kept it a secret — even from her friends and neighbors. Her husband, who also worked in the military with Americans, was killed by an explosive device while on duty during the Afghan elections in 2019. He never met their son.

Sima endured several days of tear gas, guns fired in the air, and crushing crowds at the Kabul airport, but when she finally boarded the plane that would take her and her son to safety, she felt only loss.

“When I left Afghanistan, I was very sad, unlike many who were happy,” Sima said through a translator. She fought for a better country. She did not want to abandon it.

Sima is one of 48 Afghan women from the Female Tactical Platoon now living among us in the US. But as the podcast “Stranger Becomes Neighbor” uncovers, getting on that plane two years ago wasn’t the end of her struggle.

Help from afar

When Sima, her nephew and son were dropped off by a caseworker at a hotel room on the edge of a strip mall in a suburb of Salt Lake City, it was late at night and they were hungry. They weren’t sure where they could find food. But then, there was a knock on the door and a man handed them a meal cooked by a nearby Indian restaurant. Someone was looking out for Sima from afar.

That person was a 27-year-old woman in Georgia named Becca Moss. She was 2,000 miles away, but the two women had been texting and she knew Sima could use some nourishment, so she placed the order for Indian food.

Moss had worked with Sima in Kabul, training new Afghan recruits. She was a member of the Cultural Support Team, an army unit of American women who worked closely with their Afghan counterparts from the Female Tactical Platoon and US Special Forces.

“The military is a family, no matter how you spin it,” Moss said. “They serve side by side doing the same things.”

When the Afghan women first arrived in the US, Moss and her other Cultural Support Team comrades formed an organization called Sisters of Service. Their mission was to help their fellow soldiers rebuild their lives in America. Knowing everything that Sima had sacrificed to serve alongside the US military, Moss felt a responsibility to make sure that she felt supported.

“I think we owe them a lot,” Moss said. “These women literally are an anomaly. They’re from Afghanistan, against all odds, joined the military, joined the Special Forces, and then fought for their freedom alongside US soldiers, which is more than 99% of Americans can say. I think they’ve sacrificed a lot more for America than most Americans.”

But Moss wasn’t sure if she would be able to meet Sima’s needs from so far away.

“It was a little bit of a concern because I knew nothing,” Moss said. “I know there’s a lot of Mormons out there. That’s all I know about Salt Lake City!”

She immediately contacted the resettlement agency responsible for Sima. “I’m her friend,” she told her caseworker. “I’m just trying to make sure she’s OK. I’m not [going to] leave you alone, so you might as well just accept that I’m [going to] be in your life.”

Moss found a woman living in Salt Lake City who volunteered to babysit Sima’s son so she could attend English classes. Another local volunteer also helped her move into an apartment, furnish it, find rugs and buy her shoes for the winter. With the support of the community, Sima enrolled her son in daycare, got her driver’s permit and started a job working part time as a cashier at Walmart, but she was worried about the day when government funds would stop paying her rent.

“I’m worried about how to survive with that money that I’m making,” Sima said through a translator, as she began to cry. She did not make enough money to pay her expenses, let alone send money home to her family in Afghanistan living in hiding from the Taliban because of Sima’s alliance with Americans.

On top of her financial concerns, she was stressed about her legal status in the US. Like most of the Afghans who were evacuated in a rush in 2021, she arrived as a humanitarian parolee, a temporary status that allowed her to legally live in the US for two years. She did not know what her future would hold if she was not granted asylum within that time frame.

Dabbing at her eyes with her hijab, she said it helps to talk with some of the new friends she’s made in the community or with members of the Sisters of Service who understand what she’s going through.

“They don’t want to be a charity case,” Moss said. “They want to be a strong individual like they were in Afghanistan.”

Staying true to the principles they internalized in the US military, Moss and the Sisters of Service have refused to leave anyone behind. But everything they’ve done for their Afghan sisters has been voluntary, outside their regular jobs and life responsibilities. There are limits to what they can do, and they’ve learned from experience that they have to spread the weight if they’re going to be able to continue. They alone cannot provide all the elements of a community.

“I think it’s really sad to see people not have enough resources initially, but the community has been really great,” Moss said, speaking about Sima’s new friends in the US. “That’s what people need is somebody who’s consistently showing up in their life.”

In June, Biden extended humanitarian parole for another two years. That extension helped Sima stay in the US legally, which was a relief because she still didn’t have asylum.

Today, Sima is studying English in Virginia — she relocated again — and is working and raising her son. And last month, she received some good news — she was granted asylum. But 17 of her sisters, fellow Afghan veterans from the Female Tactical Platoon who have also applied for asylum, are still waiting to hear back on their cases.

In the meantime, Moss and the Sisters of Service and other military veterans who served in Afghanistan continue to advocate for the Afghan Adjustment Act, a bill designed to speed up the asylum process for people like Sima who are already in the US.

The bill would also help get more allies out of Afghanistan — including more service members like Sima.

Listen to the first episode of “Stranger Becomes Neighbor” below:

An earlier version of this story was originally published by KSL.com.