My mother was born in Sambir, Ukraine, and my father in Przemyśl, Poland. They both spent their childhoods as refugees.

They lived among displaced Ukrainians who fled to Austria and Germany as the Red Army advanced in July 1944. My grandparents’ decision to abandon their homes and leave everything behind saved my parents from the tyranny of Soviet occupation.

They were some of the 200,000 Ukrainians who chose to live in exile rather than be repatriated to the Soviet Union. They organized themselves around civic, education, cultural and political interests. Within these circles, Ukrainians produced newsletters, pamphlets and books to connect themselves with one another and to inform the world about the country’s history.

This publishing effort was in addition to work done by Ukrainians who immigrated for economic reasons to North America beginning in the 1890s, and those who lived abroad for political reasons during the revolutionary era in the early 1920s.

I am the custodian of these publications in my role as a librarian developing, making accessible and researching Ukrainian — and other Slavic-language collections at the University of Toronto Libraries.

Our library’s Ukrainian holdings — whether they were published in Ukraine under Austrian, Polish or Russian rule, in independence, or in refugee centres and diaspora communities — offer a perspective on Ukraine’s distinct history that sets it apart from Russian President Vladimir Putin’s belief that Ukraine was “entirely created by Russia.”

Ukrainian culture and history in libraries

Librarians and libraries across the world play a role in preserving and sharing Ukraine’s cultural history. They acquire western observations about Ukraine or material printed on its territories. And people can learn a lot from these resources.

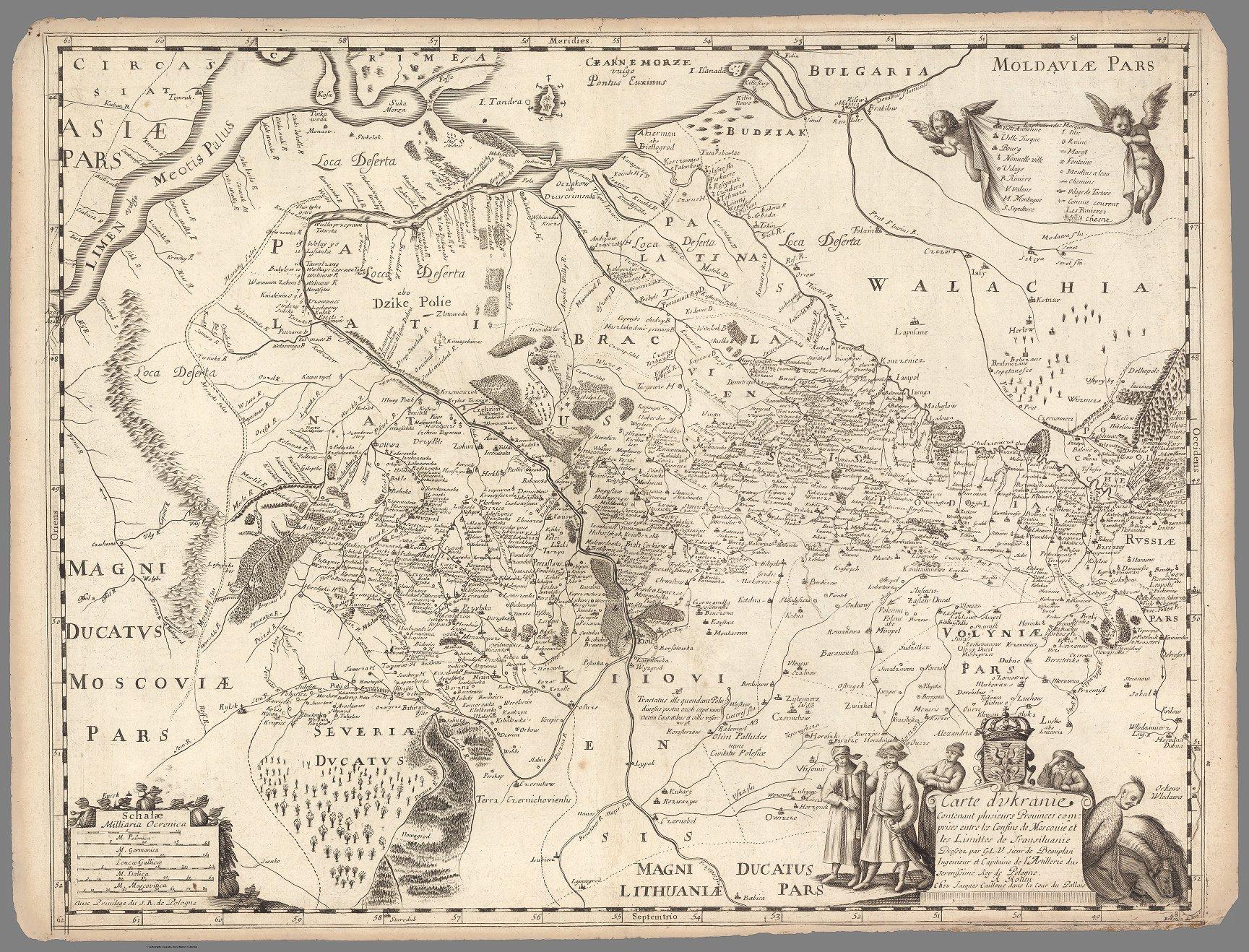

French architect and military engineer, Guillaume le Vasseur de Beauplan’s map, Carte d’Ukranie, first represented the country as a discrete territory with delineated borders in 1660. It was commissioned by King Ladislaus IV of Poland to help him better understand the land and its people to protect the territory from enemies (particularly Russia).

In Histoire de Charles XII (1731), Voltaire similarly describes and textually maps Ukraine as the country of the Cossacks, situated between lesser Tartary, Poland and Muscovy. He said: “Ukraine has always wanted to be free.”

Other material in our libraries bears physical traces testifying to the horrors of Soviet rule. At the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, a Gospel Book printed in Pochaiv, Ukraine, between 1735 and 1758, and written in Church Slavic, bears a notation that it was given to the St. Michael’s Golden-domed Monastery in Kyiv, “to remain forever irremovable from the church.” However, this monastery was destroyed on Stalin’s orders in the mid-1930s and volumes from the library were sold by the Soviet government.

But books also enter library collections through more honest means — refugees sometimes donate their personal libraries to universities. At the University of Toronto, we have a hand-written, water-coloured issue of a Ukrainian prisoner-of-war periodical entitled Liazaroni (Vagabond) (1920). It was produced in an internment camp near Cassino, Italy, where tens of thousands of Ukrainians were held captive after fighting in the Austro-Hungarian army.

Among the close to 1,000 books and pamphlets that were published by Ukrainian people displaced after the Second World War, is a children’s story I remember reading from my youth, housed at the University of Toronto. The book, Bim-bom, dzelenʹ-bom! (1949), tells the story of how a group of chickens and cats help put out a house fire. A passage from the book can be applied to Russia’s war against Ukraine:

“Roosters, chickens, and chicks, and cats and kittens know how to work together to save their home. So, you, little ones, learn how to live in the world, and how in every danger to defend your native home!”

Ukrainian print and digital knowledge at risk

Today, teams of archivists and librarians are heeding a similar call and are working to save Ukrainian library and museum collections. Their efforts echo the work of the Monuments Men who, during the Second World War, gave “first aid to art and books” and engaged in the recovery of cultural materials.

The General Staff of the Armed Forces of Ukraine says Russian military police are destroying Ukrainian literature and history textbooks — Russian forces have also bombed archives, libraries and museums.

They have destroyed the archives of the Security Service in Chernihiv which documented Soviet repression of Ukrainians, they also damaged the Korolenko State Scientific Library in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest library collection.

Archival staff in Ukraine work day and night to scan paper documents and move digitized content to servers abroad. Librarians and volunteers also pack and make plans to evacuate books.

Maintaining and preserving online archives or digital objects during wartime is difficult. They are as precarious as print material because they rely on infrastructure in the physical world. Computer equipment attached to cables and servers needs power to work. Power outages or downed servers can mean temporary or permanent loss of data.

Over 1,000 volunteers, in partnership with universities in Canada and the United States, are participating in the crowd-sourced project called Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO) to preserve and secure digitized manuscripts, music, photographs, 3D architectural models and other publications. So far, the team has captured 15,000 files, which are accessible via the Internet Archive.

Just as libraries have collected, preserved and shared knowledge held by their own institutions over the past century, they are now sharing this knowledge globally so that when the war is over, Ukraine can see its cultural treasures rescued and restored.![]()

Ksenya Kiebuzinski is the Slavic resources coordinator and head of the Petro Jacyk Resource Centre at the University of Toronto Libraries. This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit website dedicated to unlocking the ideas of experts, under a Creative Commons license.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?