‘Don’t Look Up’ exposes the absurdity — and consequences — of climate change denial

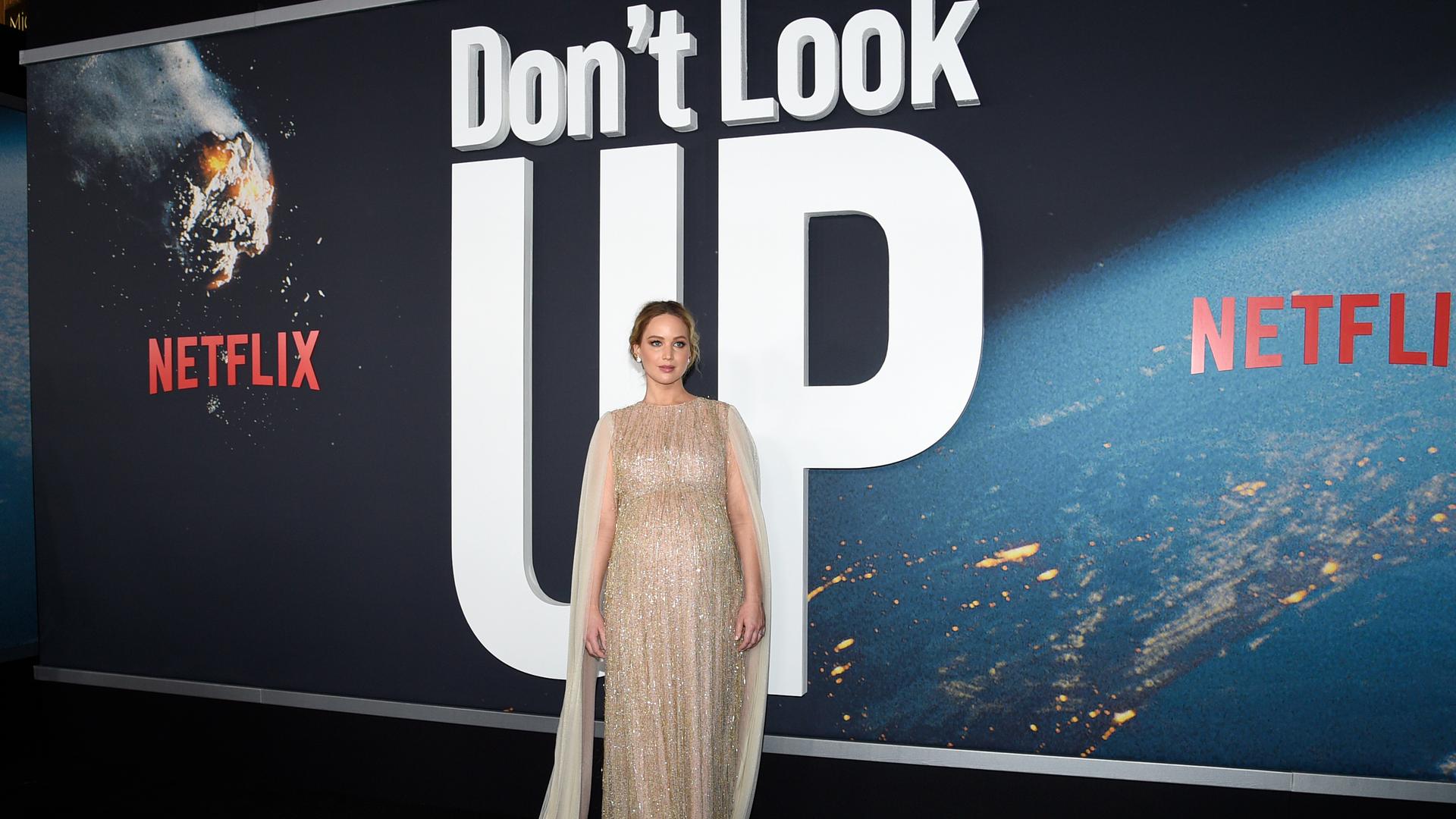

Climate fiction just got a huge boost of star power with the film, “Don’t Look Up.”

The film, which stars Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, Tyler Perry, Meryl Streep, Cate Blanchett, and Ariana Grande, is about a pair of scientists who discover a massive, “planet-killing” comet hurtling towards Earth with just six months until impact.

The scientists sound the alarm about the impending disaster and try to get a distracted world and the self-serving people in power to do something about it — clearly an allegory about the political obstacles to climate action and the false promises of future technological fixes.

Michael Mann, distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University, knows a thing or two about the frustration scientists feel in the face of climate denialism and political inaction. He thinks director and screenwriter Adam McKay and the story’s co-creator, David Sirota, pulled off a difficult challenge.

“If you talk about climate, sort of, straight up, you’re going to lose some of your audience, you’re going to raise their hackles,” Mann says. “Climate change denial has become ideological among some. And so, if you make it about something completely different, but the undertones and the message really are sort of informing [the audience’s] understanding, hopefully, of the climate crisis, then maybe you can get some people to listen, to open up their ears.”

“[T]he front door is bolted shut. … You can’t just barge through with facts and figures. So you look for that side door. And I think humor and satire is that side door…”

Climate change denial is a firm part of the ideology of the American right today, Mann observes. “As I like to say, the front door is bolted shut. … You can’t just barge through with facts and figures. So you look for that side door. And I think humor and satire is that side door, and that’s what they’ve done here.”

Related: Faith and politics mix to drive evangelical Christians’ climate change denial

In his recent book, “The New Climate War,” Mann stresses the importance of communicating both urgency and agency — the situation is grim, but it’s not too late to do something about it.

Mann worries that some people will come away from the film with the wrong message. It’s possible to watch the film and think, ‘we’re doomed,’ but that isn’t the real message of the film, if you think about how its events unfold, he says.

“I don’t want to spoil the film for [people] who haven’t seen it yet, but suffice it to say that there was a path forward that was safe and reliable — and that’s the path that wasn’t taken,” Mann says. “And so, without giving it all away, if they had addressed this problem in the way that scientists said it needed to be addressed, then there was a real chance for success. But instead, they listened to the voices of tech billionaires, and that led us down the wrong path. I think that’s the critical message.”

Related: Decades of science denial related to climate change has led to denial of the coronavirus pandemic

The film also satirizes the belief that there exists some sort of technological fix that will someday solve the problem of climate change. A techno-fix down the road is a way of postponing actions the world needs to take right now, while it still can, Mann insists.

“The more you look into these potential interventions scientifically, the more you realize there are all sorts of potential unintended consequences,” Mann says. “That’s one fundamental problem. But even more problematic, I would say, from the standpoint of the politics and the policy, it provides a convenient argument for delay. It’s a crutch for polluters who want to say, ‘Hey, look, we can solve this problem down the road. So let’s continue to burn fossil fuels and generate economic growth, because we’ll figure out how to solve this problem later. Trust us.’”

“We’ve got to cut our carbon emissions by 50% within this decade to avert catastrophic warming. We’re not going to do that with new breakthrough technology.”

“We’ve got to cut our carbon emissions by 50% within this decade to avert catastrophic warming,” he continues. “We’re not going to do that with new breakthrough technology. We can solve this problem using existing renewable energy. There are plenty of studies that demonstrate that. The obstacles aren’t technological at this point, they’re entirely political. It’s really that simple.”

Related: How the Trump administration’s climate denial left its mark on the Arctic Council

In the film, even in the face of something as clear-cut as a planet-destroying comet, politics and greed prevent from people from banding together and finding a solution. It’s an imperfect metaphor, Mann says, because the climate crisis is unfolding more slowly.

“We don’t go off a cliff at 3 degrees Fahrenheit warming of the planet,” Mann explains. “What we’re doing instead is we’re walking out onto this minefield, and the farther we walk out onto that minefield, the more danger we encounter.”

At the same time, “we know that 3 degrees Fahrenheit warming is really bad,” he says. “A lot of bad things will happen if we exceed that amount of warming. It’s something we really want to try to avoid at all costs.”

What the film gets right is the way that political ideology is used to divide people and “to favor an agenda of inaction that, in the case of the film, costs us the entire planet,” Mann says. “But in the case of climate change, if we fail to rise to the challenge, it will cost us a livable planet.”

Ironically, the predictions about climate change, going back to the 1960s, are proving to be remarkably accurate, despite the protestations of climate change deniers.

“[I]f we just stand back and look at the big picture — the warming of the planet — it’s actually exactly as was predicted a half century ago by none other than ExxonMobil, the world’s largest publicly traded fossil fuel company.”

“[I]f we just stand back and look at the big picture — the warming of the planet — it’s actually exactly as was predicted a half century ago by none other than ExxonMobil, the world’s largest publicly traded fossil fuel company,” Mann points out. “Their own scientists successfully predicted both the rise in carbon dioxide concentrations if we remained addicted to fossil fuels…and the warming that that would cause.”

In the film, the phrase “don’t look up” becomes a rallying cry for a campaign to ignore impending doom.

“Don’t look up” is exactly what climate “inactivists,” as Mann calls them in “The New Climate War,” want us to do.

“The forces of inaction — polluters and those promoting their agenda, politicians and front groups and conservative media outlets — they don’t want us to look up [and see] something that’s plainly evident.”

“The forces of inaction — polluters and those promoting their agenda, politicians and front groups and conservative media outlets — they don’t want us to look up [and see] something that’s plainly evident,” Mann says. “All we have to do is use our two eyes and we would see [the comet]. Well, that’s true with the climate crisis, isn’t it? We’re watching it play out in real time now, in the form of these unprecedented extreme weather disasters. All we have to do is just look out at what’s happening.”

This article is based on an interview with Steve Curwood that aired on Living on Earth from PRX.