Residents of informal settlements among the most at risk from climate change

On the morning of July 13, Boota Messaih ate breakfast at his home in Karachi, Pakistan, like always.

Then, the pastor and grandfather walked out his front door, and slipped into the Gujjar Nala, a drainage ditch flooded by this year’s historic monsoon rains.

The ditch, now carrying stormwater, sewage and trash, was 20 feet deep that day, according to his family.

“We were helpless,” said his wife, Parveen Messaih, last month, standing near where her husband fell and died. “No one was able to take him out because the water level was so high.”

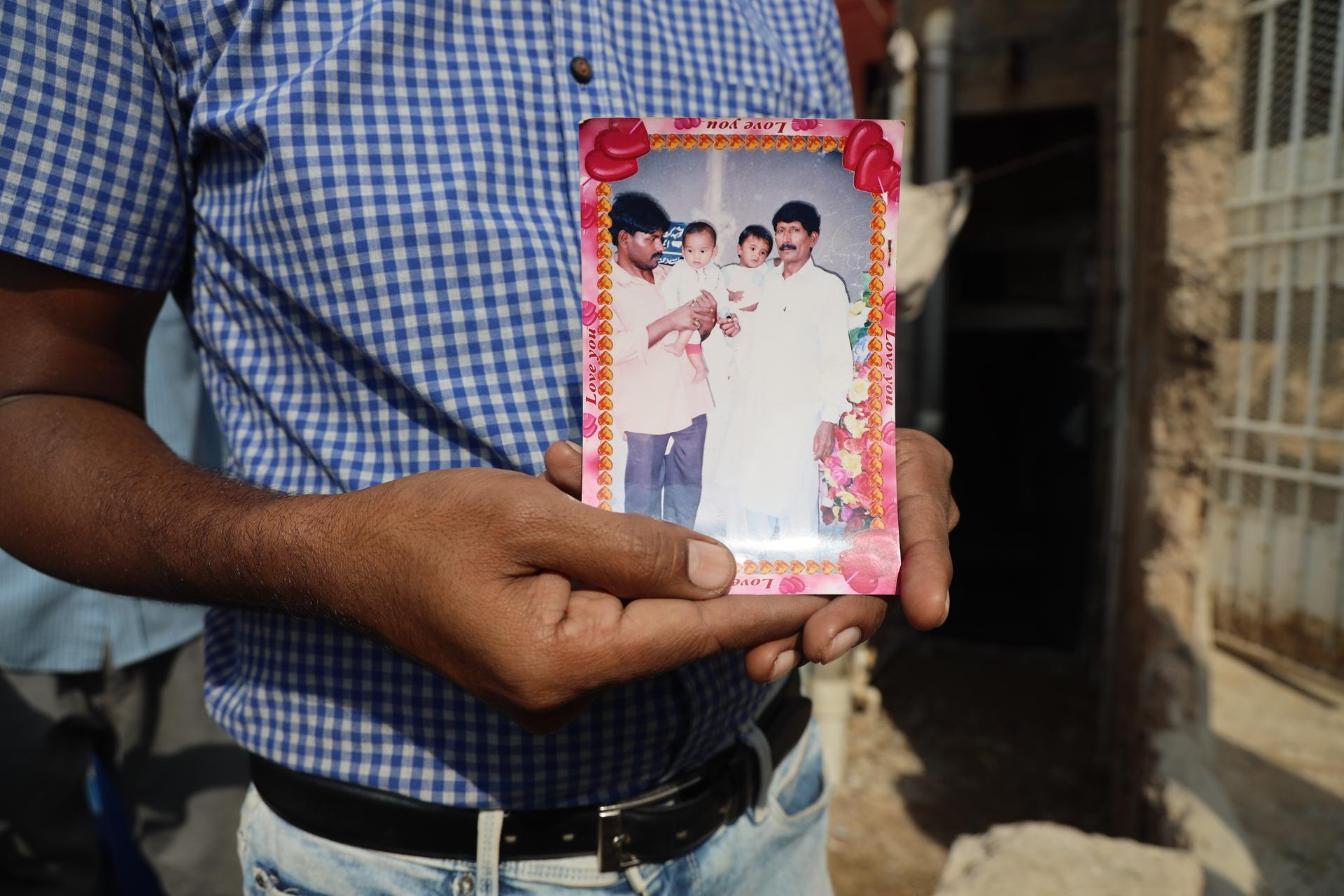

Boota Messaih had lived in the informal settlement on the banks of the drainage ditch for 50 years. The church where he served as pastor was just a few doors down, and his family remembers him as a loving man, a good provider, and well-respected in the community.

More than a billion people around the world are estimated to live in informal settlements, or slums, in homes that are built illegally — and precariously — on floodplains or steep slopes not connected to basic infrastructure like sewage systems.

As climate change fuels stronger storms and more intense rainfall, a UN climate report released this year warns, the poor and those living in informal settlements are the urban-dwellers most vulnerable to the impacts of global warming.

Flooding deaths alone from this year provide plenty of examples. In April, flooding in Durban, South Africa, hit the city’s townships particularly hard, and in August, flooding in Seoul, South Korea, killed a family living in a basement apartment. Many such apartments in the capital were originally built as bunkers and were not designed for permanent living, but are comparatively cheap in the expensive city.

‘His body was in front of us’

The two-story house that Boota Messaih shared with his extended family always flooded a little during the monsoons, but the Messaih family said they had never considered it dangerous before.

“Before this incident, nothing had happened like this,” Boota Messaih’s son, Sohail Messaih said.

Emergency responders eventually came. The water was so black with sewage, it took over an hour for them to retrieve Boota Messaih’s body, according to the family.

“His body was in front of us,” Sohail Messaih, said. “But we couldn’t get it out of the water.”

Now, the Messaih family said they would like to leave their neighborhood near the open drainage ditch, but they can’t afford to rent or buy a house anywhere else. Like their neighbors, they’re members of Pakistan’s Christian minority, one of the poorest in the country, and they don’t legally own the land their house is on.

An earth-mover at work in front of their house is providing some measure of hope. It’s widening the drainage ditch and building a wall to separate it from the neighborhood.

But until Karachi builds formal sewage and trash systems in this area, people here fear clogging will keep causing flooding. For now, the family has built a homemade barrier of corrugated metal along the drainage ditch.

“After this incident, we think this might happen again,” Sohail Messaih said. “So, we put this barricade up, and then, other people followed.”

They say it won’t stop floodwaters from breaching the banks of the drainage ditch, but it might, at least, stop someone else from slipping in.

Unsafe housing

David Satterthwaite, a lead author on a section on urban adaptation in a 2014 UN climate report, said illegally built homes are themselves often unsafe, and often also built in risky areas.

“It cheapens the cost of the house,” he said. “So, they’re doubly disadvantaged.”

Satterthwaite said that in the 1970s and 1980s, cities would frequently bulldoze these communities. He’s worried that it may become a trend again.

“You can see people concerned with climate change looking at these informal settlements and thinking, ‘OK, we’ve got to move these people. It’s too dangerous for them,’” Satterthwaite said. “[And] then, [they] adopt the same techniques [to] forcibly move the people.”

But he argued this is a bad idea.

“Government schemes to try and move people living in some of the most-dangerous sites have almost never worked because they impose solutions on the inhabitants,” he said.

This is true for the Messaih family’s next-door neighbor near the Gujjar Nala in Karachi.

The government recently demolished the front rooms of Elizabeth Younus’ house in a bid to clear more land around the flood-prone drainage ditch. But now, she’s just living in the back rooms that are still standing. Land elsewhere in the city is too expensive, she said.

“We can’t even afford food, how can we pay the expensive rents in other parts of the city?” she said.

Satterwaithe said community-driven solutions to climate risk tend to work better.

He points to a different informal settlement in Karachi — Manzoor Colony — where authorities planned to demolish about 1,000 flood-prone homes. In 2021, the community mapped the area, revealing dozens of drains clogged by sewage and trash that made flooding worse.

“They made a whole plan,” said architect Arif Hasan, who advised on the project.

Hasan said the communities argued those drains could be cleared, and most of the homes then spared.

“The decisions that were taken after this reduced the number of affected families from over 1,000 to about 58,” he said.

The latest UN climate report highlighted another success story of a community-led effort: a coastline community in Freetown, Sierra Leone, that chose to limit new building and construct new drainage ditches to limit future flooding.