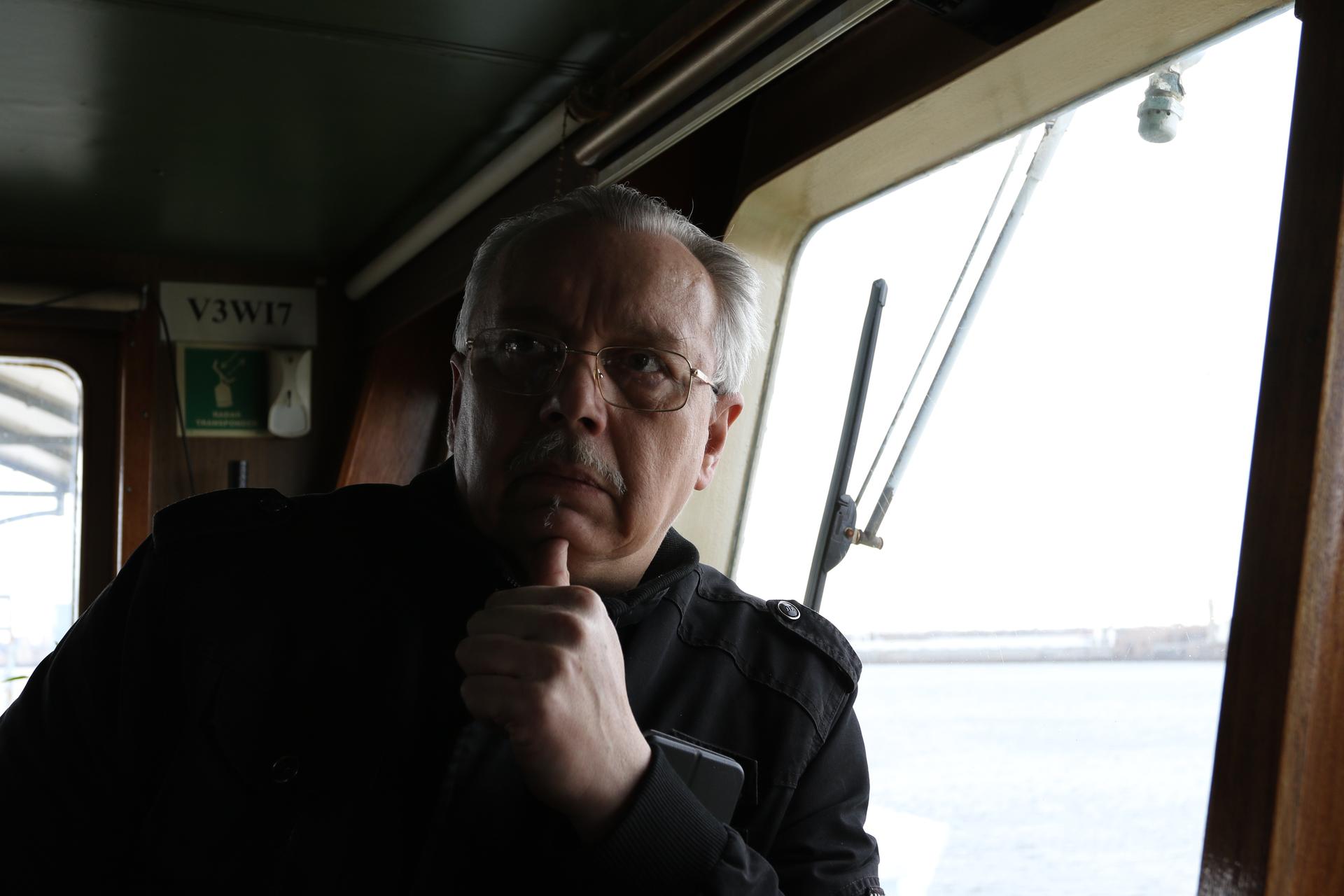

On a windy day in March, the cargo crew of Ocean Force headed down the ship’s ladder to pose for a group photo.

After eight months aboard the merchant vessel at Philadelphia’s port, the seven-member, all-Ukrainian crew is preparing to finally step onto US soil any day now.

Related: Amid war in Ukraine, India maintains ‘strategic partnership’ with Russia

Last year, Ocean Force was seized by US federal authorities after its previous owner ran into financial and legal issues. Capt. Gennadiy Shevchenko and the rest of the crew were brought in to keep the heavy load carrier running. But for months, they have not been paid. And, due to expired visas and international law requiring ships to be maintained at all times, the crew has been unable to leave the port.

In the meantime, the war in Ukraine that began on Feb. 24 has shattered any plans that he and other crew members had for their futures.

“We had [been] planning to go back to Ukraine, you know, buy a new car, maybe settle down in your apartment, you know. Illusion. Yeah. Now, we have what we have.”

“We had [been] planning to go back to Ukraine, you know, buy a new car, maybe settle down in your apartment, you know. Illusion. Yeah. Now, we have what we have,” said Shevchenko, who has spent more than 35 years as a seafarer.

Related: As the war rages in Ukraine, Radio Sputnik occupies the airwaves in American heartland

Shevchenko and the rest of the Ocean Force crew are among the hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian and Russian seafarers who boarded ships before the war began and are now in limbo at ports around the world. Many are struggling to get off their ships — to return to Europe, or go somewhere else — as companies try to sustain the staff they need to support supply chains. Some are also stranded at Ukrainian ports.

Getting flights back home, accessing bank accounts, collecting paychecks and finding a place to go are just some of the myriad challenges that the seafarers are now faced with.

Ukrainians make up about 5% of the global shipping workforce, according to the International Chamber of Shipping.

Because the Ocean Force has now been sold, and outstanding debts are expected to be paid, the crew will finally be able to get off — and experience at least some relief through a new temporary visa. For at least the next 18 months, Shevchenko will reside in the US.

“We [are] happy [about that] because the Ukrainian border is closed,” Shevchenko said.

But for many others, the future is still uncertain. In the US, Ukrainian seafarers are up against strict mobility issues.

“The big issue right now is with Customs and Border Protection,” said Eric White, Florida’s inspector for the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). “By and large, [Ukrainians] are not allowed off the ship even to go to Walmart or something, much less go home.”

White said that decisions are being made by Customs and Border Protection on a case-by-case basis at ports, prohibiting many Ukrainians from setting foot on dry land — even those with valid visas.

The fear is that Ukrainian seafarers will overstay their visas and not return to their ships.

Related: Russians in Georgia help to evacuate Ukrainians

“And even when you have the exceptional circumstance where they are allowed to go home, it’s done with an escort of an armed guard all the way until their plane leaves the ground,” White said.

It’s not just seafarers who are frustrated. Last month, several major shipping organizations sent a concerned letter to the departments of Homeland Security and Treasury, first reported by The Wall Street Journal.

In part, it reads: “We understand there are some field offices that are prohibiting disembarkation of Russian and Ukrainian crew members even though they may have valid US visas,” which is “creating confusion for these individuals and operational challenges for the shipping community.”

In some cases, to speed the process along, Ukrainian seafarers who spoke to The World said that they’ve been advised to request asylum — not necessarily because they want to stay in the US, but because it would give them a legal route to get to an American airport.

Across Philadelphia’s bay, Ukrainian Vlad Schmelkov said that he was trying to make quick decisions about his future in the limited days that he was at the port.

Initially, Schmelkov said that he wanted to stay in the US. But he quickly changed his mind, because it’s expensive, and he wants to be close to his family. He started the process of applying for a US visa so that he could access Philadelphia’s International Airport just down the road and hopefully go to a country where his family would be fleeing to.

“Yeah, it’s not [a] very easy decision,” he said. “Now, I’m mulling over this issue.”

Because his ship is Russian-owned, Schmelkov was nervous that he would end up in St. Petersburg soon — a place where he personally knows of other Ukrainian seafarers who have been harassed or disappeared after authorities went through their phones.

“I thought that I should sign off from this vessel because it’s really dangerous [for] Ukrainians to [go to] Russia.”

“I thought that I should sign off from this vessel because it’s really dangerous [for] Ukrainians to [go to] Russia,” he said.

When word came through that his ship would be going to Panama first, he decided to stay on board — make more money — and then hopefully hop off there before the ship made its way to Russia.

For Ukrainian Oleksandr Dudnyk, whose ship docked in Savannah, Georgia, getting a visa wasn’t a problem. Instead, he needed to first get permission from his company to leave.

After repeatedly asking to be let out of his contract, which was already expiring, Dudnyk finally went on strike.

“After two hours when we sent this letter, we received information about our crew change,” he said, adding, “It was awesome. I was very happy.”

He’s now headed back to the Ukrainian border where he plans to evacuate his mother and move her to a neighboring country.

As for other seafarers who remain stuck — including several fellow crew members on his ship who are still also trying to get off — Dudnyk said that he aches for them.

“We are very worried for our families, and it’s very hard to stay very far from them when something happens at home that you can do nothing [about].”