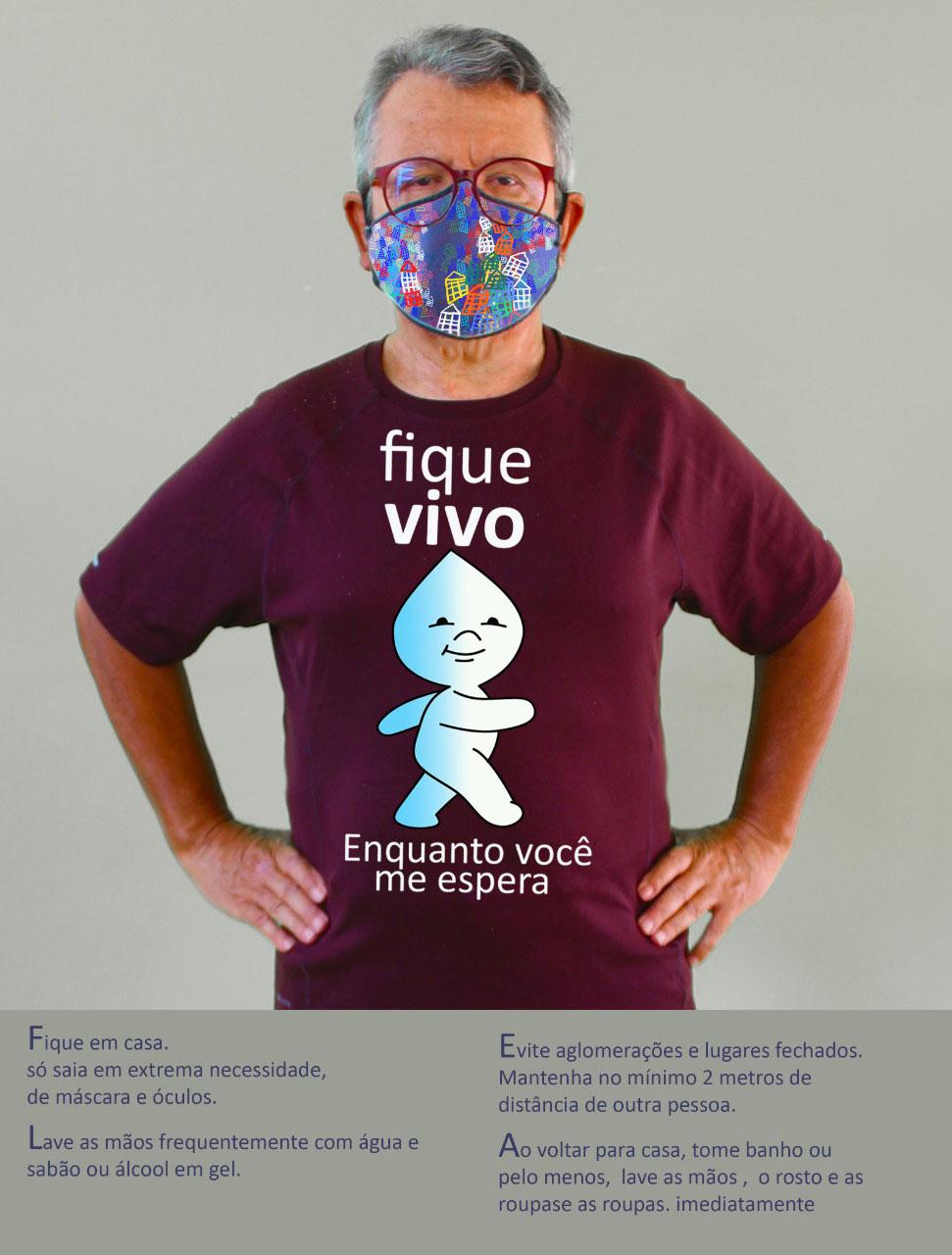

Some of the earliest childhood memories for many Brazilian kids look something like this: A jolly, life-sized white tear-drop-shaped figure waving and giving hugs to a crowd of kids.

He wears a huge smile and the logo of Brazil’s universal health care system: SUS.

In a video posted by the Ministry of Health a few years ago, he’s introduced to rows of children in an auditorium in Rio de Janeiro’s Cidade de Deus favela.

“What’s his name?” asks the man on the mic. “Zé Gotinha,” shouted the kids.

Zé Gotinha is roughly translated as “Droplet Joe.” He’s like Smokey the Bear for Brazil’s vaccination program.

Related: Bolsonaro accused of crimes against humanity over negligent COVID response

Three generations of Brazilians have grown up with Zé Gotinha, and many say the little guy is responsible for the country’s overwhelming vaccine acceptance despite resistance from President Jair Bolsonaro and some of his supporters.

The mascot is shaped like a drop of liquid because that’s how the polio vaccine was administered in Brazil, back in the 1980s. He’s been a huge part of the country’s world-renowned vaccination program over the last three decades, making appearances at health clinics and vaccination drives across the country.

Related: Copa America soccer championship in Brazil draws protest while coronavirus cases rise

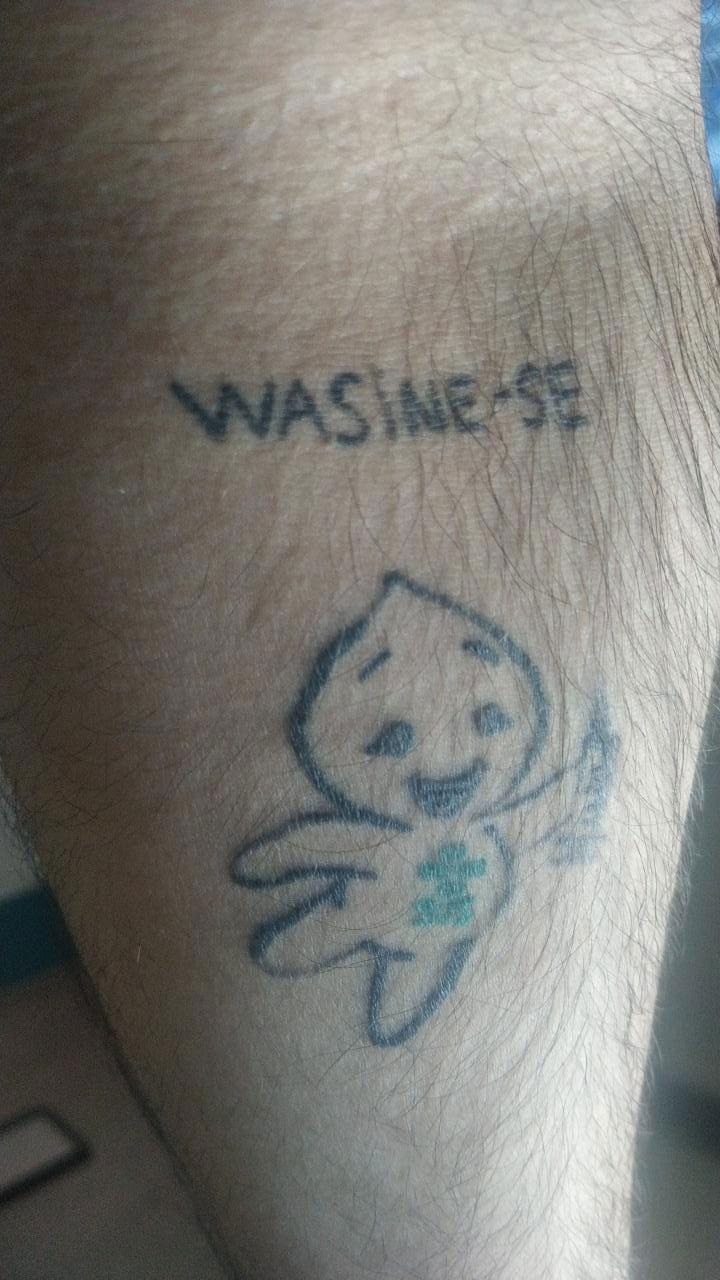

“There is nothing better to show the world that vaccinating is good,” said Wasim Prates-Syed, a Brazilian health researcher and a member of the Pro-Vaccine Union.

“I grew up with Zé Gotinha. I remember taking my vaccine. I remember hugging people dressed up as Zé Gotinha. I even have a Zé Gotinha tattoo.”

That is the size of the affection many Brazilians have for their beloved Zé Gotinha.

The character made his debut shortly after the end of the Brazilian dictatorship in 1985, at a time when Brazil was fighting a losing battle against polio and other infectious diseases. Parents and children were suspicious of government vaccination efforts.

Darlan Rosa, the artist who created Zé Gotinha, said that at the time, the army was involved in the vaccination program and they were pretty heavy-handed. When children heard them coming they hid. There was a lot of resistance due mostly to a lack of information.

“I created Zé Gotinha as a way to communicate with the children,” Rosa said. “That was my goal, so that a child would say, ‘Dad, today’s vaccination day, would you bring me to the health clinic to see Zé Gotinha?’”

It worked. According to Rosa, in the era of polio, Brazil vaccinated as many as 20 million children on a single day. The disease was eradicated in Brazil by 1989.

In a cartoon from the same year, Zé Gotinha looks a little like “Casper, the Friendly Ghost,” but with a pointier head. He dances through a neighborhood protecting children from ugly monsters who represent infectious diseases like polio, tetanus or measles.

Despite the progress, resistance persists when it comes to COVID-19 vaccinations.

Jair Bolsonaro has long said he will not be vaccinated. Last year, he rejected early offers to purchase vaccines from Pfizer and other companies and joked that the COVID-19 vaccine might turn you into a crocodile. In late October, Facebook removed a video where he falsely claimed the shot could cause AIDS.

Related: ‘Bolsonaro, get out!’: Protesters across Brazil call for president’s ouster

“We are going through a crisis, not just with vaccinations against COVID, but also a crisis over the coverage of the other vaccinations,” said Renata Rivera, a doctor in São Paulo.

Zé Gotinha has been largely absent under the Bolsonaro government, which has mostly rejected the use of the beloved character to promote health safety and COVID-19 vaccinations.

“Where is our beloved Zé Gotinha? Bolonsaro sent him away because he thought he was leftist,” said former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to supporters in March.

The same month, Jair Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo Bolsonaro, a senator, even tried to rebrand the lovable character. He tweeted out a picture of Zé Gotinha holding a syringe, like a machine gun, the president’s signature pose.

Related: Brazil’s small farmers tackle food insecurity, hunger amid the pandemic

“I was so angry,” said Zé Gotinha’s creator Rosa.

“Everyone was. I still get choked up. On social media, there was a huge response in Zé Gotinha’s defense. These are the children from yesterday — the parents of today, vaccinated by Zé Gotinha.”

Rivera said that Brazil has lost ground against polio, tuberculosis and measles and doubts whether Zé Gotinha could jump-start Brazil’s immunization program at this point.

But Syed, the Brazilian health researcher, credits Zé Gotinha for Brazil’s recent COVID-19 vaccination rate success.

“We have seen that although there has been this anti-vax discourse, people are still going out and getting vaccinated,” Syed said. “And that’s also due to Zé Gotinha and this whole campaign going back years showing the people that vaccines are good.”

Rosa said he’s concerned about the anti-vaccine movement, in particular, in the United States, where he has two grandchildren.

I just want everyone to be protected, he said.

That’s what Zé Gotinha wants, too.