Iselle Toledo entered Colombia without permission a few years ago.

“When I came in, nobody stamped my passport,” said Toledo, who suffers from kidney problems and still hasn’t been vaccinated. “If I were a legal resident, it wouldn’t be a problem to get the vaccine. But for me, it’s hard.”

That’s what brought her to Juntos Se Puede (Together We Can), a foundation housed in an old, two-story home in Bogotá. The garage is often full of people. Some are looking for help with residency applications. Others have come to ask about vaccines for the coronavirus.

Related: Brazil takes its kite-flying passion to a whole new level

Many Venezuelan migrants still haven’t gotten their shots because vaccination centers in Colombia require national ID cards or proof of residency.

This summer, South America accounted for a quarter of all COVID-19 deaths as a deadly surge swept through countries such as Colombia and Brazil. Now, with vaccination rates increasing in the region, cases have fallen and most countries have dropped travel restrictions.

But Venezuelan migrants and refugees who have moved to different parts of South America — often making long journeys on foot — have struggled to get shots because of legal requirements at vaccination centers. And that could slow down efforts to stamp out the coronavirus in the region.

Colombian President Iván Duque initially said that undocumented immigrants would be left out of the nation’s vaccination program. Colombia is home to 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees — 1 million of whom are undocumented.

Duque said in a radio interview last year that opening vaccination to undocumented people would “invite a stampede” of Venezuelans to cross the border in search of vaccines.

But Colombia changed its policy this past summer as the global supply of vaccines increased.

Related: French Polynesia and New Caledonia see deadly COVID-19 surge

This month, the Ministry of Health ordered city governments to make lists of migrants who need vaccines, so that they can get shots later this year.

And in Bogotá, undocumented migrants can now get vaccines if they prove they have applied for Temporary Protected Status.

But applying for TPS involves filling out an online form that includes a 70-question survey and attaching documents that show the applicant has been in the country since February when the Colombian government decided to provide protection to all Venezuelans living here.

For some migrants, these hurdles have discouraged them from getting vaccinated.

“If I could just show up at a vaccination center and fill out a form, I would do it. But I haven’t gone because it’s confusing, I don’t know how to use the internet well.”

“If I could just show up at a vaccination center and fill out a form, I would do it,” said Angel Bruges, a 50-year-old Venezuelan migrant who makes orange juice and sells empanadas at a street stall in Bogotá. “But I haven’t gone because it’s confusing, I don’t know how to use the internet well.”

Related: Randomized study of mask-wearing illustrates their importance in preventing the spread COVID-19

Venezuelans have also struggled to get their shots elsewhere in South America.

In Peru, where there are more than 1 million Venezuelan migrants, less than 10% have been vaccinated according to official statistics. That’s because vaccination centers in some parts of the country are still asking for national ID cards.

In Chile, many undocumented Venezuelans have stayed away from vaccination centers over fears of being deported. Chile started to deport undocumented migrants from Haiti and Venezuela this past spring.

The United Nations is urging governments in South America and elsewhere to simplify vaccination requirements and stop asking for national ID cards.

And the Organization of American States says it’s not even that expensive to vaccinate all of the Venezuelan refugees in Latin America.

David Smolansky, the organization’s envoy for the Venezuelan refugee crisis, says it would cost around $165 million to vaccinate the 5.4 million displaced Venezuelans in Latin America.

And international donors recently pledged more than $1.5 billion in aid for Venezuelan refugees at a conference in Canada.

While this money will go to all kinds of needs, Smolansky says it shows how vaccinating Venezuelan migrants in the region is achievable.

The amount needed to vaccinate Venezuelan migrants “is approximately 13% of what was donated at the conference,” Smolansky said. “And vaccinating Venezuelan refugees will not only protect them but also the societies in Latin America and the Caribbean that are receiving them.”

Victor Uribe, from Together We Can, says that his group is trying to help undocumented migrants fill out TPS applications so that they can legalize their stay in Colombia and get vaccinated.

Three times a week, the group has social workers with laptops available at its offices to help migrants apply for TPS.

While that still takes some effort, many migrants say it’s worth the trouble.

Oriana Fernadez, who was visiting the organization for a medical appointment, said it took her three days to fill out the TPS application form online.

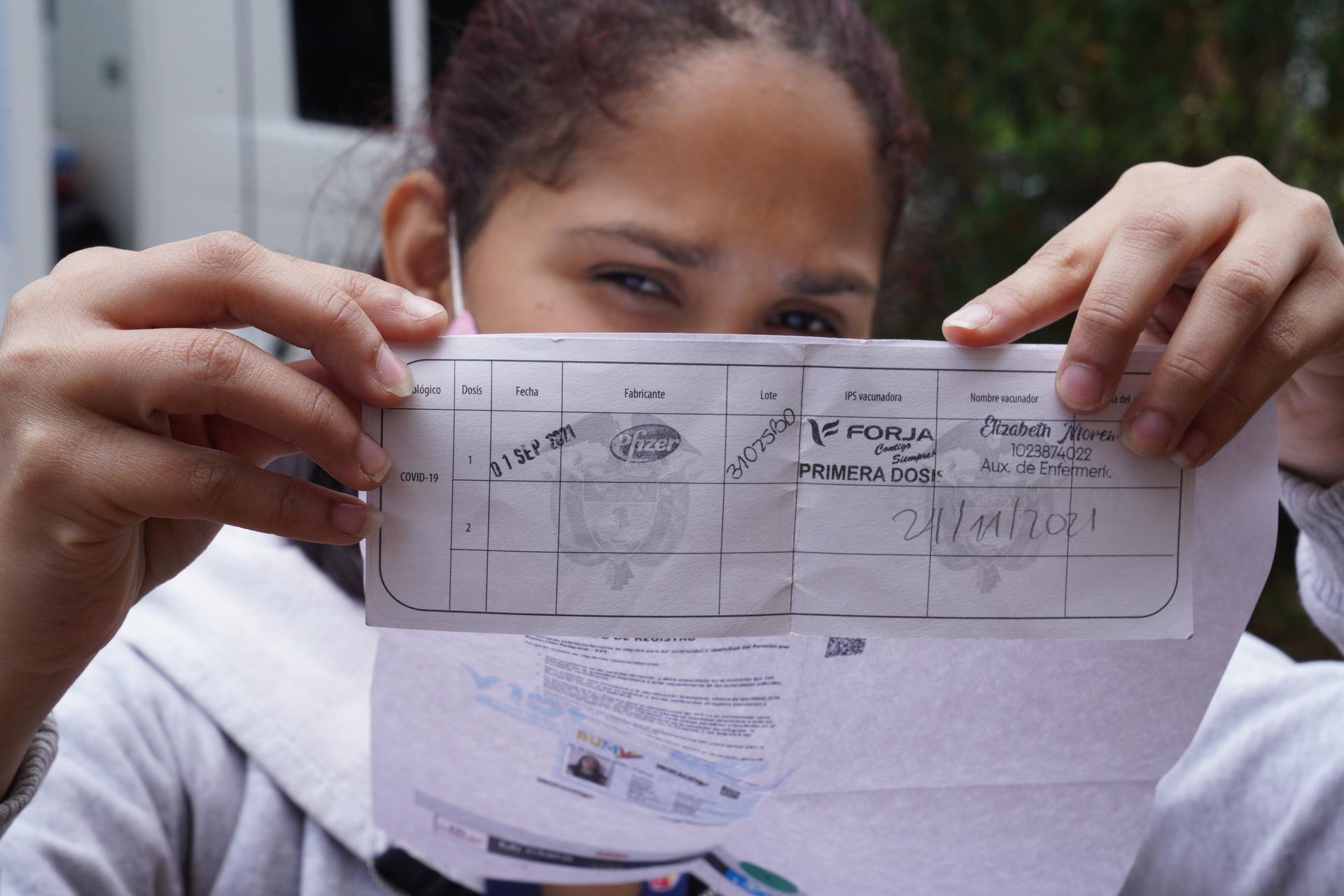

While she waited for the doctor, she unfurled a sheet with a QR code that proved she had completed the online application.

“With this, you can get vaccinated,” she said, pointing at the sheet. “It was tough. But we all need to get vaccinated so we can get rid of this virus.”