Tour guide Alex Rocha stops at a large square flanked by stately colonial buildings while leading a group of tourists through the historical center of Cartagena, Colombia.

The group looks at a marble statue of Christopher Columbus and a government-issued sign that explains how the largest building on the square was used by the Spanish colonial government as its customs office.

But there’s nothing that explains the square’s connection to the slave trade — except for Rocha’s voice:

“This is where they auctioned our people. They brought them here and sold them as merchandise.”

“This is where they auctioned our people,” Rocha tells a group of Black American travelers, through a speaker. “They brought them here and sold them as merchandise.”

Amid anti-government protests that swept over Colombia this summer, some demonstrators also set their sights on public monuments and plazas, igniting a debate over who is celebrated with monuments and place names.

Related: Colombian Deportado Coffee’s founder hopes to open a conversation about US immigration

In southwest Colombia, Indigenous protesters knocked down statues of a Spanish conquistador who founded the cities of Cali and Popayan, while in Bogotá, the government removed a Christopher Columbus statue after riot police stopped demonstrators from taking it down themselves.

In Cartagena, Rocha has been trying to change the historical narrative for several years using less radical methods: He leads tours that focus on the city’s Afro-Colombian history, and tries to show visitors how Cartagena’s past connects with the present.

“First of all, we show people the historical center of Cartagena, which was built on the backs of Africans,” Rocha, 51, said. “We talk about how we got here, but at the same time what is going on with Afro-Colombians today.”

Rocha’s tour takes visitors to an 18th-century wall built by the Spanish to stop pirates from attacking the city. Here, he tells the story of an Afro-Colombian naval commander who was whitewashed in many historical paintings.

The tour passes colonial-era churches where Rocha talks about how the Catholic Church punished slaves who held onto their religious beliefs. Then he heads to Bazurto, a chaotic street market where Afro-Colombian vendors hustle to sell fruits, vegetables and fish.

Rocha also takes visitors to Getsemani, a neighborhood of narrow streets and 200-year-old homes. It held a reputation for drug and crime problems — until recently.

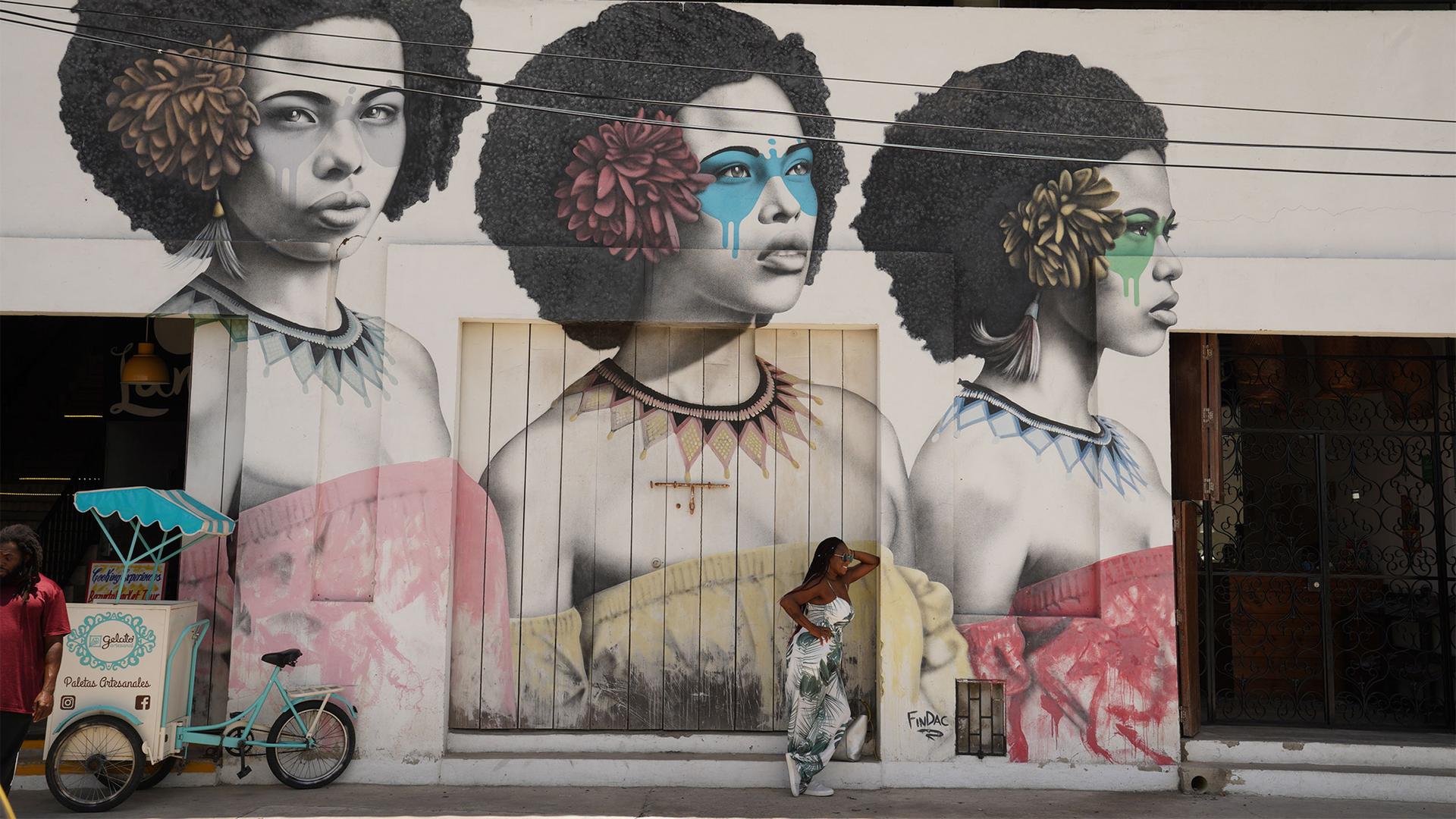

Investors have been buying up the historical homes and turning them into restaurants and boutique hotels. Murals that celebrate the city’s Black heritage have been painted by street artists and bars featuring live salsa music welcome tourists.

But Rocha points out that the neighborhood’s turnaround has also been driving out many of its Black residents, who are no longer able to afford the rent.

Rocha said his goal is not just to provide visitors with historical facts, but to show the city through “a Black man’s perspective.”

“It is time for us to claim our rights.”

“It is time for people out there — especially minorities — to come together and have a voice, so that this society understands that they have caused a lot of damage to these ethnic groups,” he said. “It is time for us to claim our rights.”

While Colombia was a Spanish colony, from the early 16th-19th centuries, at least 250,000 slaves were shipped into the area, which was then known as the viceroyalty of New Granada. Most arrived through the port of Cartagena, where, in the early 17th century, 25% of the population was made up of African slaves, according to historical records.

Slavery was abolished in 1851, 30 years after Colombia gained its independence from Spain. Today, however, Colombia’s Black population is still behind in areas like educational achievement and access to basic services like the internet. According to a national census conducted in 2018, 30% of Afro-Colombians live in “multidimensional poverty,” meaning they lack access to adequate housing, formal employment and basic schooling. In that same census, 3 million people around the country self-identified as Black. Afro-Colombian organizations, however, have complained about the census’ methodology, and estimate that the number could be up to three times higher, with descendants of Africans making up anywhere from 15% to 20% of the population.

Related: In Colombia, companies expedite vaccine rollout with private funds

Rocha, who is a native of Cartagena, grew up in one of the low-income neighborhoods on the city’s periphery, and started out working as a guide after he learned to speak English on his own.

Initially, he worked for companies that offer walking tours of Cartagena’s historic district, listed as a UNESCO world heritage site, thanks to its colorful, well-preserved colonial architecture.

But he encountered Black tourists who encouraged him to veer “off the script” and turn his sights to Afro-Colombian heritage. A new business idea flourished as more Black Americans encouraged Rocha to conduct tours focused on Black culture in Colombia, he explained.

“I started doing private tours until people started to put my name in Black travel groups and that’s how everything started,” he said.

Rocha now runs his own tour company, which also takes visitors to nearby locations like the island of Baru and San Basilio de Palenque, a village founded in the early 1700s by runaway slaves.

Everyone is welcome on his tours, he said, but Rocha admits that 99% of his clientele are Black Americans and Black travelers from Canada and Europe, who are curious to see how the African diaspora has fared in different parts of the world.

Related: Colombia loosens COVID restrictions to save the economy as deaths soar

Some travelers said they joined Rocha’s tour because it shows a side of history not often told in textbooks.

“We’re taught about the Spaniards, and the different places they colonized. But what we aren’t taught is the history of the enslaved people that built these countries.”

“We’re taught about the Spaniards, and the different places they colonized. But what we aren’t taught is the history of the enslaved people that built these countries,” said Norelle Combest, a visitor from Chicago, who recently took Rocha’s tour of Cartagena.

“I just wanted to hear the experience of a place where there are lots of Blacks from a Black person’s point of view.”

Mac Shed, from Maryland, said that he joined the tour because it provided a unique perspective. “I just wanted to hear the experience of a place where there are lots of Blacks from a Black person’s point of view,” he said.

Rocha said that through activism and art, the city’s Afro-Colombian population has become increasingly visible. That is now reflected in murals, statues and public spaces named after Black Colombians.

While many Afro Colombians have stood out in fields, such as music and sports, Rocha points out that discrimination is still prevalent.

“We live in a country that, for generations, has been controlled by the powerful, so it is hard for minorities to succeed,” he said. “But little by little, we are making changes, and we hope things get better for our people.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?