This story was reported in collaboration with El Tímpano, a news outlet designed for and with Oakland’s Latino and Mayan immigrants.

Every Tuesday since the stay-at-home orders took hold last year, Dinora Hernandez heads to the food bank near her home in Oakland, California, to get milk, coffee, rice, canned fruit and oatmeal.

She says that the assistance has been a lifeline for her, her three young kids and her mom in El Salvador.

Related: Addressing migration requires long-term commitment, says analyst on Harris visit to Guatemala

“It lets me send cash to my mom back home, to cover the basics,” said Hernandez, who managed to continue working minimal hours at a restaurant in Oakland during the pandemic, but has yet to return to her full-time schedule.

Hernandez’s determination to keep sending cash home, like many others around the world, startled Dilip Ratha, a lead economist at the World Bank who focuses on remittances.

During the pandemic, the world’s top economists like Ratha were surprised by the amount of cash that continued to circulate around the world, often in increments averaging $200.

In all, people worldwide sent a total of $540 billion home last year, only dropping by 1.6% from 2019 — a smaller drop than during the 2009 global financial crash.

Ratha had predicted that remittances would drop by 20% last year.

They did slow down but then bounced back.

“That sense of resilience was visible in all the regions of the world. We were very worried back in April and May of last year that the remittance flows would be completely shut down.”

“That sense of resilience was visible in all the regions of the world,” he said. “We were very worried back in April and May of last year that the remittance flows would be completely shut down.”

The remittances can help build a new home, or pay for kids’ shoes, or just food.

Related: ICE contracts at local, regional level spark contentious debate

“Migrants are willing to cut costs if needed, skip a meal if needed, and send money home. That desire to help is what we continued to see during the pandemic.”

People were also able to keep sending remittances thanks to stimulus checks, Ratha added. In the United States, however, undocumented immigrants were excluded from federal aid.

In all, India received the most remittances — and might see more cash from abroad come in as the pandemic hits hard there, according to Ratha. China is the second-largest recipient — then Mexico. El Salvador is also among the top-receiving countries.

Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean increased by more than 6.5% to $103 billion last year. El Salvador is a top recipient of remittances, with nearly $6 billion flowing in from abroad last year — reflecting about 24% of El Salvador’s economy.

The amount also represents far more than the four-year, $4 billion in aid that the Biden administration has pledged to try and stem migration from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala.

Related: ‘How to Report a Hate Crime’ booklets empower Asian Americans amid rise in discrimination

Hernandez had also heard the news about El Salvador’s Congress approving the use of bitcoin, the cryptocurrency, as legal tender. Relatives in El Salvador sent her articles about the announcement because Salvadoran officials say bitcoin might make it easier and cheaper to send money from abroad.

Hernandez is intrigued but, like many others, isn’t sure how bitcoin works.

“Look, I know very little about it,” she said. “It’s just very strange.”

Ever since coming to the US two years ago, she has sent cash through a Western Union-style store near her house in Oakland. The service charges $10 per transaction, which Hernandez would prefer to avoid. Her mom in El Salvador needs every cent.

“She needs it for food and her medication. My mom has diabetes and can get quite severe.”

“She needs it for food and her medication,” Hernandez said. “My mom has diabetes and can get quite severe.”

Worldwide, it’s typical that remittances are spent on urgent needs.

“This includes food and daily consumption items, but also the purchase of land and also investing in education,” said Aiko Kikkawa Takenaka, an economist at the Asian Development Bank.

Related: Many asylum-seekers are returned at the US-Mexico border under Title 42. Advocates call it a ‘sham.’

Hernandez says it’s never been easy to send money home regularly. And she recently took a big financial hit. Until just about two weeks ago, her family was sharing an apartment with her sister’s family in Oakland. But the landlord said too many people were living in the space and Hernandez had to move.

Her rent shot up from $600 a month for the single room she was sharing with her family to $2,000 a month for the small two-bedroom apartment she is now renting.

It helps that Hernandez’s partner just migrated up from El Salvador earlier this year, and is now working as a landscaper. The day before, he had spent $14 on a small plastic pool for the kids.

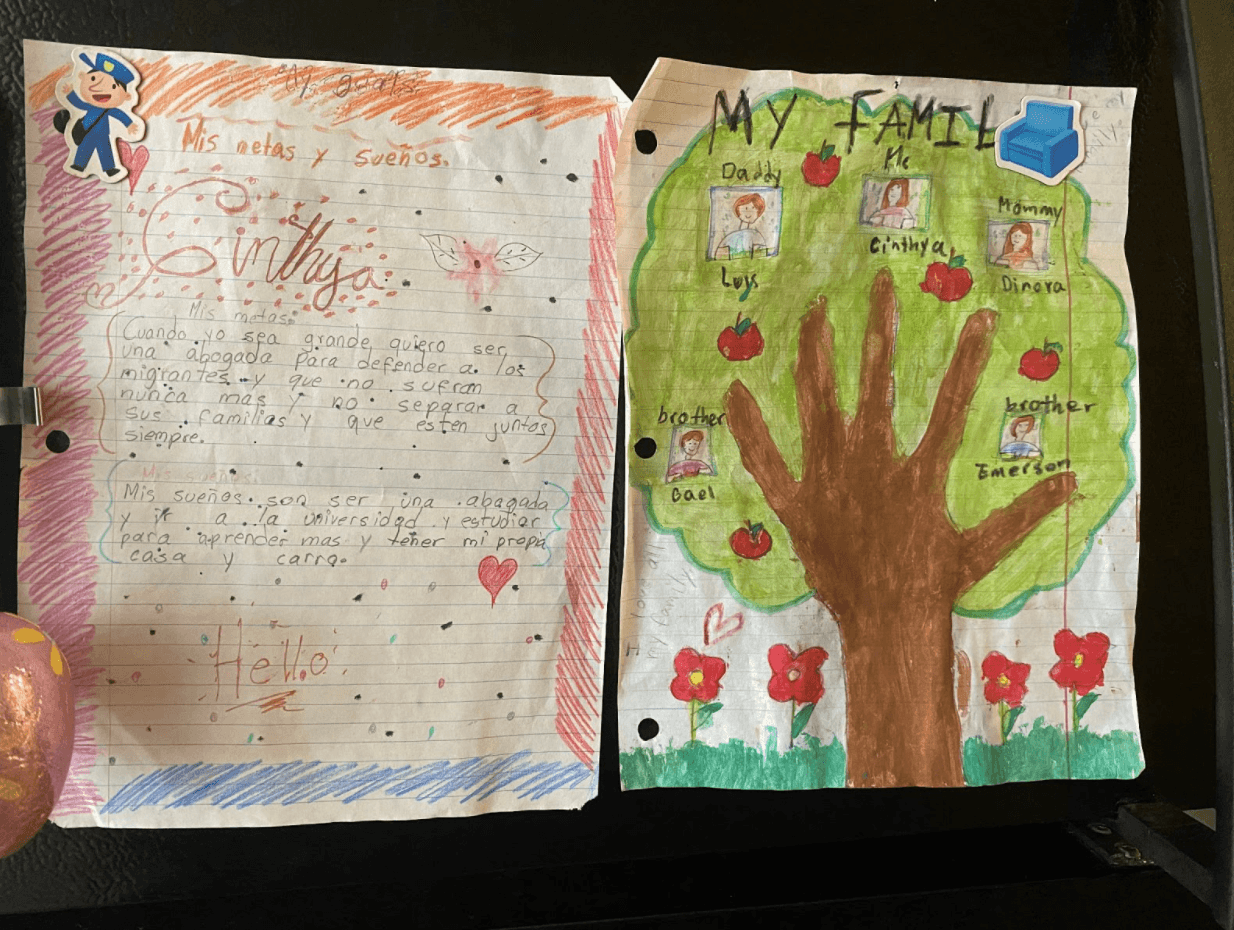

Cynthia, 11, Hernandez’s oldest child, was preparing to take the pool out to the apartment complex’s driveway and fill it up. Hernandez smiles, but she is carrying a lot. She hopes things turn around in the US, so she can go back to working full time — and help her family back home more.

“I want to send more money home,” she said. “Perhaps instead of $100, I can send $200 a month.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?