On a Tuesday in May, several dozen people gathered in front of an administrative building in Woodstock, Illinois, a town of about 25,000 people, 54 miles northwest of Chicago.

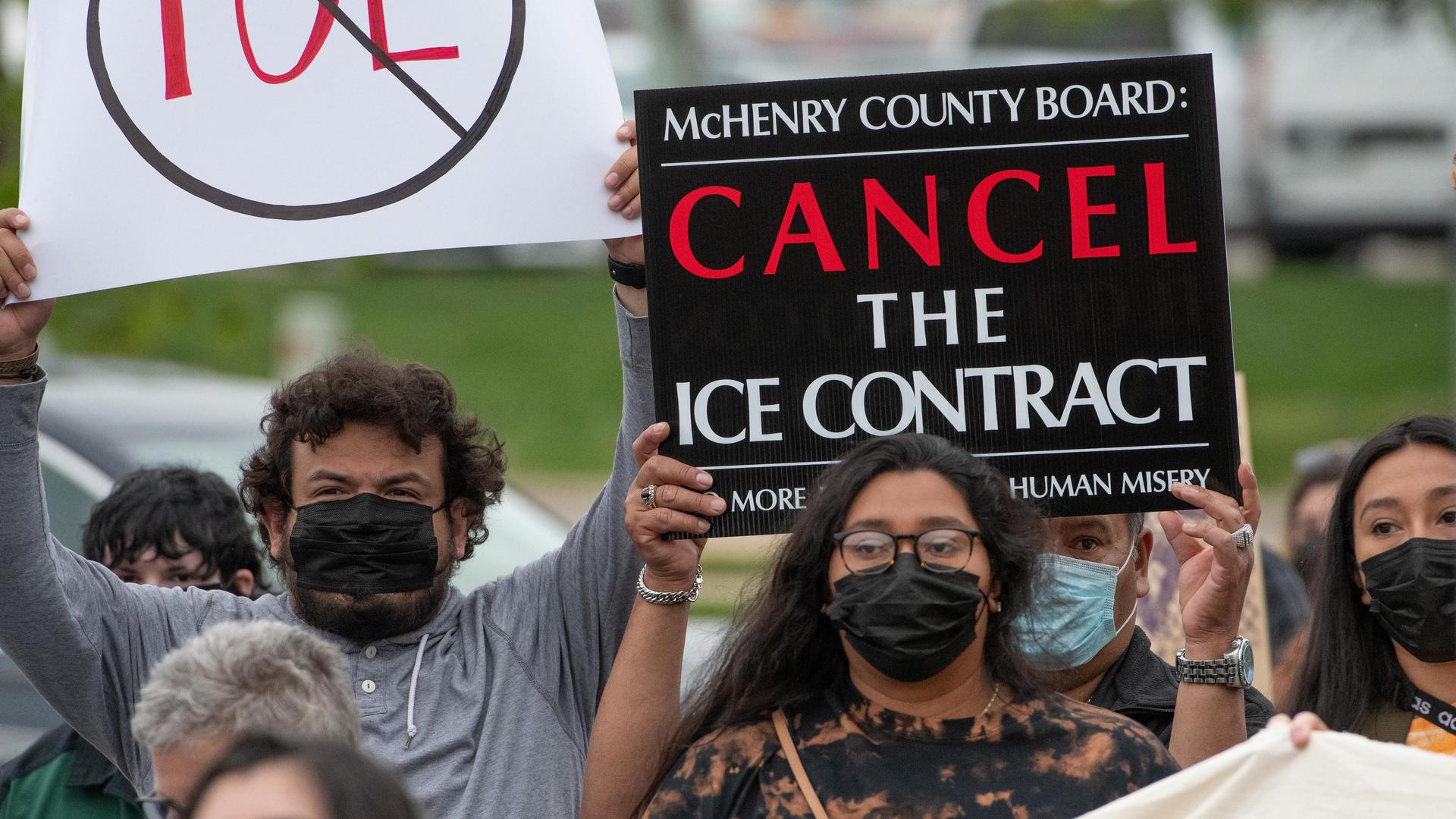

Organizers held up signs that read: “Community not cages,” and “Cancel the ICE contract.”

The McHenry County Board would meet inside that building later that evening. On their voting agenda was a resolution to phase out the county jail’s contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement — also known as ICE — and stop detaining undocumented immigrants.

Immigration advocates around the county, like those in Woodstock, have waited since January for President Joe Biden to address immigration detention after he announced changes to contracts between the Department of Justice and private prisons. Biden said his goal is to end racial disparities and pave the way for fair sentencing.

Related: Immigration rights activists call on Biden to end private detention

Most recently, the administration terminated its contracts with two county jails, the Bristol County Sheriff’s Office in Massachusetts and the Irwin County Detention Center in Georgia — both under federal investigation for allegations of abuse against immigrants in their custody. Many advocates applauded the move as a first step.

But without any federal mandate to end immigration detention in county jails and private detention centers, advocates will continue to look to local and state lawmakers to act, said Silky Shah, executive director at Detention Watch Network, an advocacy group against immigration detention.

“It’s so important whenever you have these fights at the local level to show the impact of detention in your community, to signal to the federal government, ‘Hey, actually this is not OK and this shouldn’t be happening.’”

Public pressure is increasing, she said.

“It’s so important whenever you have these fights at the local level to show the impact of detention in your community, to signal to the federal government, ‘Hey, actually this is not OK, and this shouldn’t be happening,’” she said.

Related: Biden’s day one promise to end ‘Remain in Mexico’ may go unfilled

Pushing for statewide measures

In April, Essex County in New Jersey canceled its ICE contract. Other states, including California, Maryland and New York are pushing for statewide measures to prevent counties from entering contracts with ICE.

Canceling existing contracts can be a tough sell, especially when these communities have depended on those federal dollars and the jobs that come with running detention centers, Shah said.

But the pandemic did decrease the number of immigrants being detained nationwide, Shah said. That has left people wondering whether the same amount of detention centers are necessary.

“With COVID, there was a reduction in the number of people detained for a bunch of reasons because the border was closed because a lot of people were continuing to be deported, and [there were] less enforcement operations,” she said.

Related: A therapists’ network supports immigrants, advocates during pandemic

Still, In Illinois, the McHenry County Board voted to keep their county jail’s partnership with ICE. The jail has beds for 250 immigrants. The county receives $95 a day from the federal government for each detainee in custody. But during the pandemic, many of those went unused.

According to county data, for the fiscal year 2020, the jail’s average daily number of undocumented immigrant detainees was 189, compared to 279 and 275, for 2019 and 2018, respectively.

It was a contentious debate. The majority of board members weren’t convinced that ending the ICE contract would make a difference. Instead, they’d prefer to wait for the federal government to issue a mandate.

“This county board does not have the ability to solve the immigration problem in this country, and that’s why I’m not voting to eliminate the contract that we have with ICE.”

“This county board does not have the ability to solve the immigration problem in this country, and that’s why I’m not voting to eliminate the contract that we have with ICE,” said county board member Joseph Gottemoller.

Others were concerned about where the detainees would go if the contract ends, and if moving detainees across state lines to other states would be an inconvenience for their families.

“To send people someplace else — I will be voting no on this for that fact alone. The money is not the issue to me, I believe we can cut budgets,” said Jim Kearns, another board member.

Related: ICE gets sued to release immigrant detainees amid COVID-19

A moral issue

Undocumented immigrants like Johannes Favi said this is a moral issue, and that more board members should have voted to end the contract. Favi is an immigrant from Benin who spent close to a year detained at the Jerome Combs Detention Center in Kankakee, another Illinois county jail that contracts with ICE. He also wants to see ICE contracts end — and detention altogether. He drove to Woodstock from his home in Indiana to speak at the meeting.

“I know [migrant detention] is wrong. And if nobody stands to do something against it, well, it’ll keep happening.”

“I do that because for me, it’s just common sense to fight for what is right. And I’ve lived it. So I know this is wrong. And if nobody stands to do something against it, well, it’ll keep happening,” Favi said.

Amanda Hall, co-founder of the Coalition to Cancel the ICE Contract in McHenry County, and who lives in Woodstock, said many community members also supported ending the contract. Those community members want everyone to be respected and recognized, she said.

“Having ICE in our community causes fear and causes trauma … it’s not something that should be allowed.”

“Having ICE in our community causes fear and causes trauma … it’s not something that should be allowed,” Hall said.

The outcome was disappointing, said Maria Valdez, a volunteer with the Elgin Coalition for Immigrant Rights, a member of the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights. But it’s important to keep the momentum going, she said. The movement in Woodstock captivated community members who had never been involved in organizing before.

“So, I think that a silver lining of this is that it mobilizes people, right? It makes people feel angry, more passionate and engaged to be able to push for something.”

Valdez is hopeful change will come. She and other organizers want more counties and states to join the movement and show the federal government this is necessary.

“It is always a good time to do the right thing.”

“So is it a good time? It is always a good time to do the right thing. And are we going to win? I think we have a good chance,” she said.