Oscar-nominated ‘Wolfwalkers’ blends environmental, spiritual history of Ireland

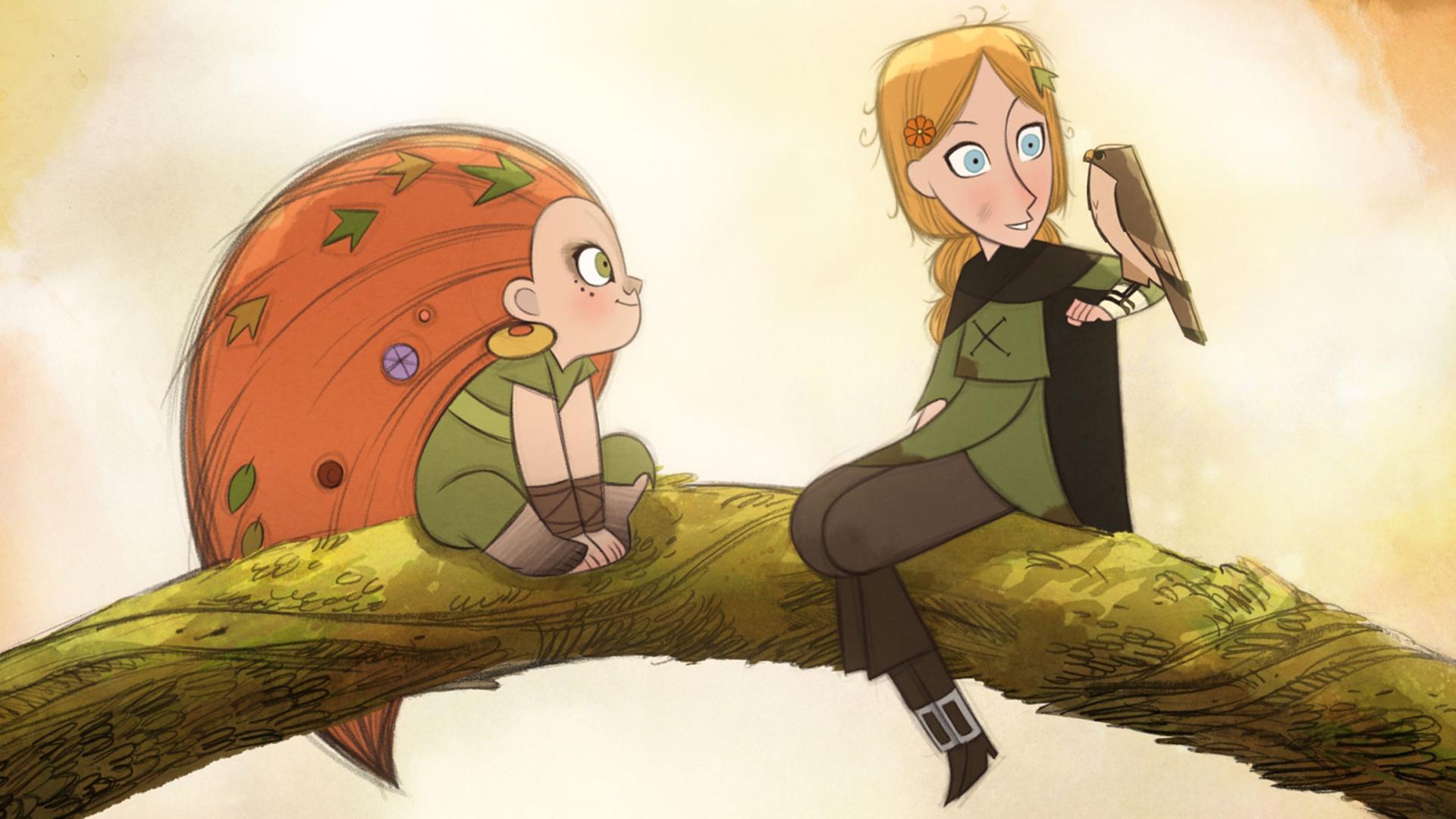

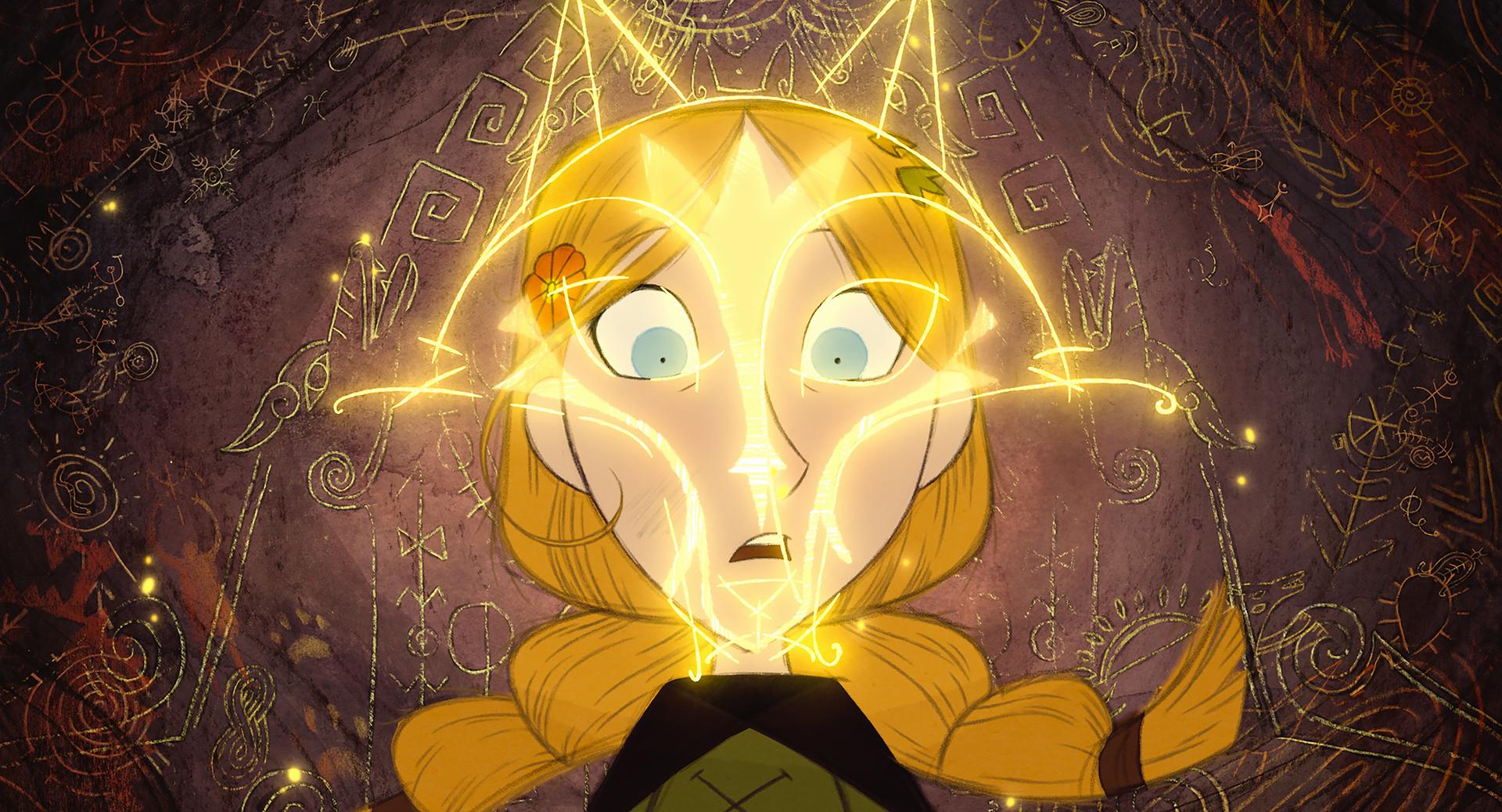

The movie “Wolfwalkers” is based on a fantastical premise that comes straight out of Irish folklore.

The film, made by a small animation studio in Kilkenny, Ireland, is up for an Oscar this weekend, up against giants like Disney and Pixar.

One of the main characters is a young girl who magically shifts between girl and wolf. And she’s a protector of the forest.

Threatening her and her wolfpack are English colonial forces, who have invaded Ireland, and are demolishing the forests and exterminating the wolves.

Merging Irish folk stories and real events felt like a good way to tell a story grounded in both the spiritual and environmental history of the country, said Tomm Moore, co-director of the film from animation studio Cartoon Saloon.

“Ireland was called ‘Wolfland’ in a derogatory way by the English at the time because there were so many wolves,” said Moore. “And what they deliberately tried to do was, by wiping out the wolves, they were trying to wipe out a certain rebellious wildness in Irish people who identified with the wolves.”

The film is based partially on the English invasion of Ireland, led by Oliver Cromwell in the 17th century, which deforested much of the country, partly to build ships for a navy that would contribute to colonial projects around the globe.

Related: On St Patrick’s Day, Ireland fights for its image

Moore’s previous films, such as the 2014 “Song of the Sea,” are also based on Irish folklore. When he writes a movie, he describes the process as “going on a shopping trip through folklore” to find the right story to fit the themes of interest.

He said he was drawn to stories that centered the connections between people and wildlife, and the idea of humility toward the natural world.

Related: A new book explores culture within the animal kingdom

“There was a humbling, kind of animistic way of looking at the world that was contained in that folklore,” he said. “I’m trying to rediscover it for a generation that really needs to find a new way to interact with the biosphere.”

A great thing about folklore, is that the same story can have vastly different meanings to different people, said Irish folklorist Billy Mag Fhloinn.

“Folklore is a living, breathing expression of people’s thoughts, their concerns, their anxieties, their fears, their joys, their responses to the world in which they find themselves,” he said.

Mag Fhloinn said that is part of why folklore has a way of staying fresh across generations.

Related: Funky Folklore: An Interview with Eno Williams of Ibibio Soundmachine

The themes of this particular story, the violence of colonialism and environmental destruction, are not intrinsic to Irish folktales. But as long as they are in the heart of the person telling the story, the folktales can make those themes come alive, said Mag Fhloinn.

“The environment is such a huge topic nowadays,” said Mag Fhloinn. “What I can see happening is people taking old themes, taking old ideas and respinning them, or at least interpreting them in a way that’s meaningful for them and giving voice to their concerns and their anxieties.”

Director Moore said that even though the story is based in the 1600s, he hopes people come away from the film with the sense that these issues still matter today.

“There [are] a lot of modern parallels,” he said. “When we were making the movie, we were seeing footage of California on fire, Australia on fire, the Amazon on fire. So we were … animating these forests on fire, and seeing it in the real world right now.”

Just like in the movie, Moore said the current treatment of Indigenous peoples, the legacy of colonialism, and environmental destruction are all issues deeply important today.

Related: Falklands: Sean Penn renews attack on British ‘colonialism’

The film has been embraced by many environmentalists, such as Irish Minister Malcolm Noonan, who oversees the country’s national parks.

“This is a story for modern times.”

He said the movie helps to highlight the inextricable connection between people and ecosystems, and the wild animals within them.

“This is a story for modern times,” he said, “We need to go beyond the data and tell stories and use folklore, and use Irish mythology to explain and to illustrate the fact that we can’t separate ourselves from nature.”

The wolves of Ireland were exterminated hundreds of years ago, said Noonan. But there are so many species on the brink now, like birds and butterflies, that are in desperate need of conservation.

“We’re in a race against time.”

“We’re in a race against time,” said Noonan. “I feel [a] huge sense of responsibility to try to turn the story around. And for that reason, I think it’s very important that we take the messages from such a beautiful film like ‘Wolfwalkers.’”

It’s too late to go back and save the wolves, but telling their story might just help inspire people to think about saving what’s left.