Seasonal workers have long faced gender and pay discrimination. Now there’s a way to file direct complaints.

Adareli Ponce tried for 20 years to get an H-2A visa allowing her to work on farms across the US.

But Ponce said that time and time again, farm labor recruiters in Mexico told her farm work is better suited for men.

“There wasn’t much opportunity for me as a woman.”

“There wasn’t much opportunity for me as a woman,” she said.

Related: Nantucket businesses struggle without seasonal summer workers

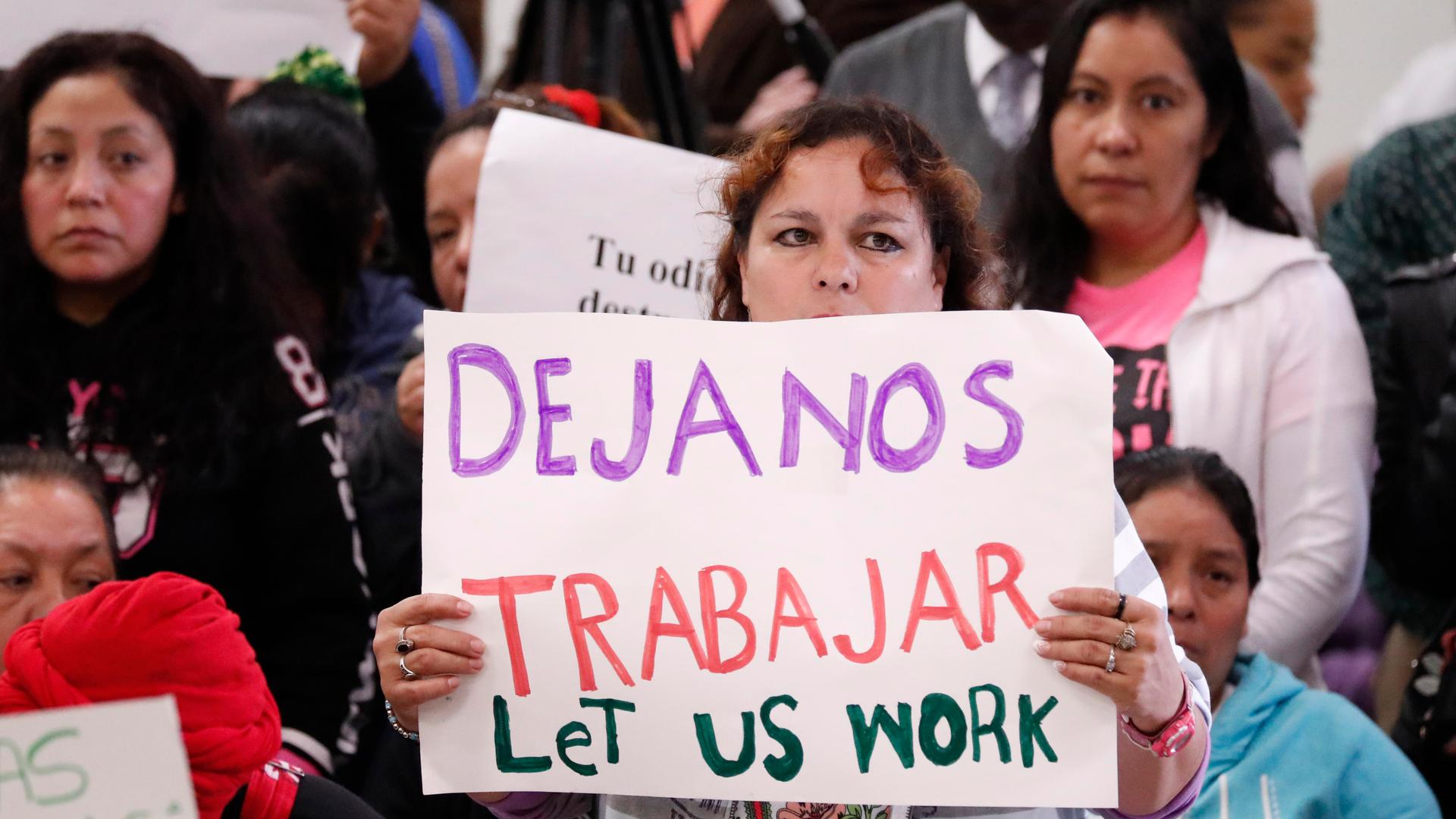

But last summer, Ponce and more than a dozen workers’ rights groups saw an opportunity to speak out against the gender discrimination and pay inequity that she and many others have faced as seasonal workers.

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) replaced the 26-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and with it came an enforceable labor chapter allowing certain workers in Mexico to unionize. It also gives migrant workers like Ponce a pathway to filing complaints directly with each government.

Ponce, now 38, and another female worker submitted a petition in March. They’re alleging gender discrimination during the recruitment process in Mexico and pay discrimination in the US under Title VII, or the Equal Pay Act.

“It’s a petition for both governments,” she said. “Please stop it with this perception people have of us [female workers].”

Ponce left her home state of Hidalgo in central Mexico after high school graduation to work at a Louisiana chocolate factory during holiday seasons like Easter and Valentine’s Day.

She received an H-2B visa, designated for nonagricultural work, mostly in factories and warehouses. But the pay is much less than what farmworkers would typically make, she said.

All of her co-workers were women, she said, sorting and packing chocolates in assembly lines. The men stacked boxes and earned more, she said.

“A group of us spoke up to demand better treatment, equal opportunities, but we were told we were problematic women and that we weren’t wanted there anymore,” Ponce recalled.

Related: US government to Filipino seasonal workers: No visas this year

Gaspar Rivera-Salgado, a project director with the UCLA Labor Center, said labor complaints to the US under NAFTA were not successful because clear, enforceable guidelines did not exist, so workers were often left wondering who to turn to for help.

Maritza Perez, who filed the petition with Ponce, testified that she submitted a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC) in 2019 after experiencing discrimination on the job in the US, but has yet to hear back. That, she said, was the only opportunity she saw to call attention to her concerns.

Rivera-Salgado said that under the new agreement, Ponce and Perez’s allegations could set a win for labor — if both countries manage to address them.

Related: Farmworkers are getting coronavirus. They face retaliation for demanding safe conditions

“This is a test of how this is going to work on the US side. … An opening to test the limits of that agreement, and especially because at the core of the agreement is the recognition of international discriminatory standards.”

“This is a test of how this is going to work on the US side,” Rivera-Salgado said. “An opening to test the limits of that agreement, and especially because at the core of the agreement is the recognition of international discriminatory standards.”

Ponce and other advocates are also calling for an independent investigation.

Rivera-Salgado said whatever comes from that could help the US, Mexico and Canada pinpoint changes to their agreement. But, he said, those updates take a long time.

“I think that one thing that we need to understand is that trade agreements are very difficult political processes in the three countries,” he said.

The US government, however, can take other steps while those changes come, said Melanie Stratton Lopez, supervising attorney with Centro de los Derechos del Migrante (CDM), a nonprofit working on labor issues in Mexico and the US.

The group is also backing Ponce’s petition.

Stratton Lopez said workers like Ponce with H-2B visas are treated differently from workers on other visas who often have free legal access in case they run into problems with their employers. The H-2B visa holders don’t have that access.

“We have workers that are very vulnerable, that are often in rural areas, and then by law, are excluded from accessing free legal services.”

“And so, that’s something that really should change. We have workers that are very vulnerable, that are often in rural areas, and then by law, are excluded from accessing free legal services.”

As for Ponce, she’s looking ahead. Even though she’s back living in the Mexican state of Hidalgo where she lives with her parents, she’s in the process of applying for another worker’s visa.

This time, she’s hopeful she’ll get to work at a farm. And she has several friends hoping for the same thing, too.

“It’s our dream,” she said. “We’d love to get an H-2A visa, but if we can’t, then H-2B will have to do. The point is to go and work.”