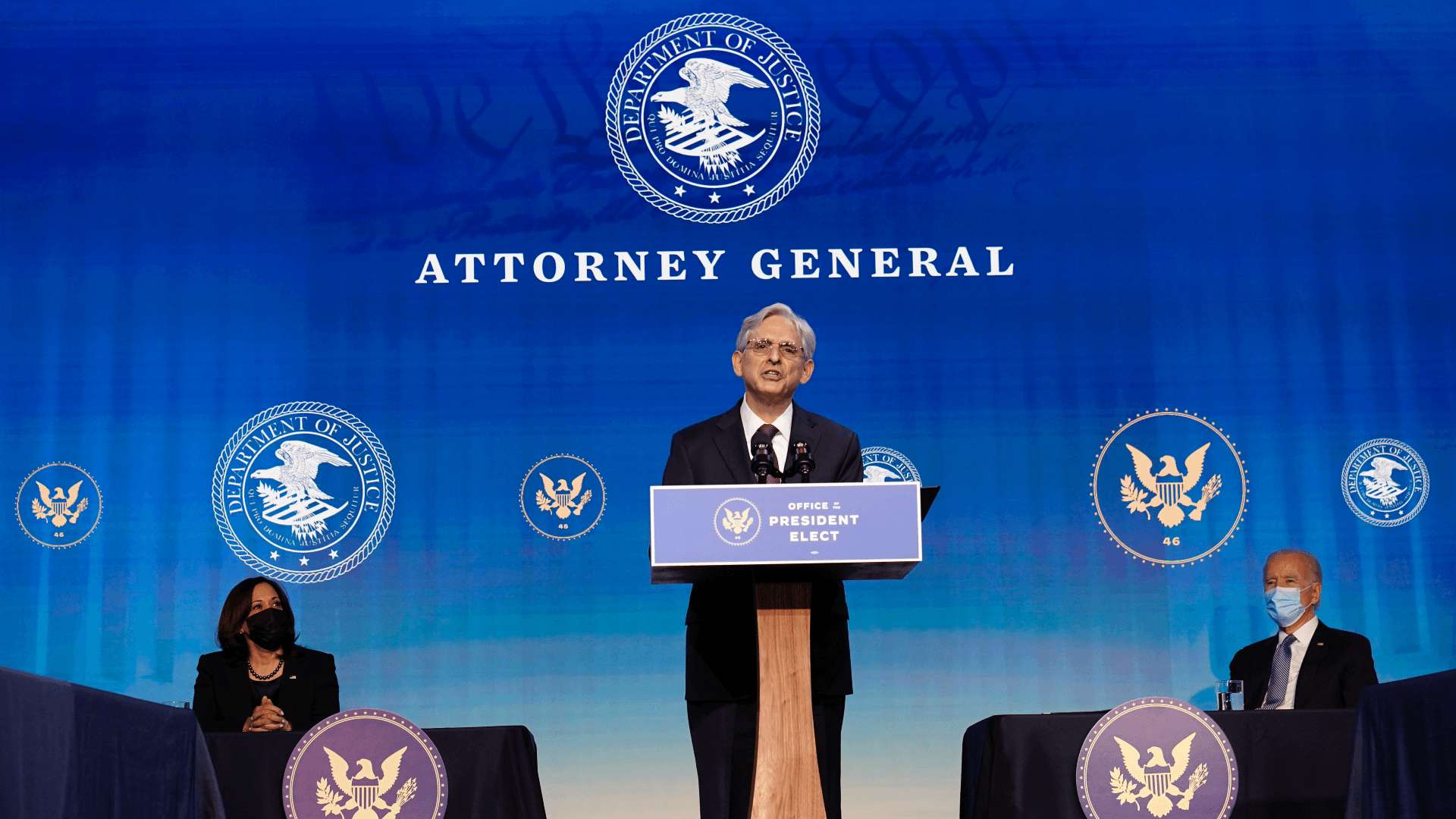

Merrick Garland — once blocked from high court — is set to become attorney general

Merrick Garland, the chief judge of what many call the nation’s second highest court, has been tapped by President Joe Biden to serve as attorney general.

Garland has spent more than 20 years on the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, which is the exclusive venue to resolve many disputes related to environmental rules and regulations.

In 2016, Senate Republicans blocked Judge Garland’s nomination by President Obama to the US Supreme Court. But with Democrats taking charge of the Senate, Garland’s confirmation as attorney general seems likely.

“[Merrick] Garland is a brilliant legal mind, who’s known as a centrist or moderate. … He’s got deep experience…and is the kind of steady hand that’s going to revitalize the Department of Justice.”

“Garland is a brilliant legal mind, who’s known as a centrist or moderate,” says Vermont Law School professor Pat Parenteau. “He’s got deep experience, having been at DOJ and, of course, most recently as the chief judge of the powerful DC circuit. I think the other thing is, Garland is the kind of steady hand that’s going to revitalize the Department of Justice. That place has really been demoralized. In addition to all the bad policy decisions that have been made at the top, that whole staff of lawyers at DOJ, some of whom I know very well, are waiting to be liberated. And I think Garland has the kind of stature and integrity to do that.”

Related: How the Biden administration might undo some of Trump’s immigration policies

Garland has a strong record on the environment and a deep respect for science, Parenteau adds. His opinions show that he digs into discovering the central environmental problem in a case and how the law is trying to address it.

“He’s the kind of judge that, if you do your homework and you’ve prepared a really good strong record, based on science, he will uphold the agency. He looks at both the text of these statutes and their purposes.”

“He’s the kind of judge that, if you do your homework and you’ve prepared a really good strong record, based on science, he will uphold the agency,” Parenteau says. “He looks at both the text of these statutes and their purposes. But he’s also quick to overturn the agency when he detects that they have not fully followed the science [or] haven’t listened to their internal experts. … He overturned EPA’s [Environmental Protection Agency] rule on fine particulates, for example, which is a very dangerous form of air pollution that causes all kinds of respiratory problems. In that particular case, he dug into the record, and he found out that the decision-makers at EPA did not follow the scientists within the agency, and he overturned them and sent it back and it produced a stronger rule.”

Garland will be faced with at least two dozen major environmental cases challenging rules of the Trump administration — on clean energy, clean air, clean water, endangered species and more, Parenteau adds.

“[I]n my career spanning now 4 1/2 decades, I’ve never seen a situation where the Department of Justice is going to be faced with having to reverse its position in so many cases, and it’s going to have to be done very delicately.”

“That’s a delicate dance because the government under Trump has taken a position in these cases and now Garland is going to have to review [those cases] and find a way, if it’s permissible, for the government to extract itself from that position, take these rules back, redo them, and then defend a new set of rules,” he explains. “[I]n my career spanning now 4 1/2 decades, I’ve never seen a situation where the Department of Justice is going to be faced with having to reverse its position in so many cases, and it’s going to have to be done very delicately.”

Related: How Biden’s Keystone XL Pipeline cancellation could test US-Canada relations

Garland will also need to address the decline of criminal enforcement of environmental law during the Trump administration. “He’s going to have to stand up and deploy the whole staff of lawyers and inspectors and investigators to recreate the criminal enforcement program,” Parenteau explains.

Part of President Biden’s climate plan is to create an Environmental and Climate Justice Division within the Department of Justice, devoted to enforcement of “disproportionate impact” on Black, Latino and low-income communities, who have suffered from institutional racism under environmental law.

“I hate to have to admit that, as an environmental law professor, but it’s true,” Parenteau says. “The siting of facilities, the lack of enforcement of basic environmental, air and water quality laws in communities, is rampant. Flint, Michigan, is just one of the symptoms of a much deeper problem of the lack of environmental law protecting these very vulnerable communities.”

This article is based on an interview by Steve Curwood that aired on Living on Earth from PRX.