Migrants restricted from entering the US due to Title 42 see double standard

Psychologist Sebastián Farías walks through a makeshift camp for asylum-seekers at a port of entry in Tijuana, Mexico, to meet with a family of eight that has been here on and off for months.

Farías is with Psicologías Sin Fronteras — or Psychologists Without Borders — a nonprofit that offers counseling services to migrants.

Related: Multilingual liaisons are ‘cultural brokers’ for refugee students in this Vermont school district

He finds the family in the middle of tents, tarps, toys and trash — and listens as they talk about the difficulties they’ve faced in Tijuana. All Farías can do is listen to them because right now, there’s no way for the family to claim asylum in the US.

The US has reopened its land borders to vaccinated travelers, but not to many asylum-seekers, even if they are vaccinated. President Joe Biden is continuing Title 42, a public health order that the Trump administration put in place at the start of the pandemic.

The order allows border officials to automatically turn back asylum-seekers — a reality that is leaving migrants in Tijuana increasingly desperate for their chance to reach the US.

“These people have serious anxiety. They have behavioral swings and don’t want to leave their tents. They face fear and depression daily.”

“These people have serious anxiety,” Farías said in Spanish. “They have behavioral swings and don’t want to leave their tents. They face fear and depression daily.”

Two weeks ago, a large fence went up around the encampment, which local officials say is for safety, but migrants say they feel they are under surveillance. No one can enter the encampment without an ID card given to them by the city government. And, no one new can move into the encampment, meaning that as families leave, it will eventually empty out.

Twenty-one-year-old Jackie is a member of the family that Farías met with. Jackie said she doesn’t want to use her full name for fear of being found by people from her hometown. She said that they fled Michoacán, a part of Mexico where powerful gangs are battling for turf and violence is an everyday occurrence.

The family tried recently to cross into the US but were turned away by US Customs and Border Protection because of Title 42.

“It was horrible. They were very racist to me,” Jackie said, describing Border Protection agents. “They treated us like insects. It’s an experience I will never be able to forget.”

Migrants and their advocates hoped that Biden would have ended Title 42 but 11 months on, White House officials say the health order is still needed to protect the US from COVID-19.

Judith Cabrera is with the Border Line Crisis Center, a nonprofit that offers advice to migrants and sometimes, a place to stay.

Cabrera said that with Title 42, the US government is convincing many migrants to turn to smugglers to cross the border. That sometimes results in deadly consequences if the migrants are left in remote parts of the desert or kidnapped and held for ransom by criminal groups.

“I don’t think there’s an awareness of the desperation they’re causing with these border policies,” Cabrera said. “So, they put it on smugglers, on the migrant community, but it’s actually coming from their policies.”

Related: US opens borders to fully vaccinated travelers from a list of countries

Last week, the United States reopened its international borders to those with a tourist visa, who could also show proof of vaccination against COVID-19. For many migrants who have already been vaccinated, this shows the double standard of Title 42.

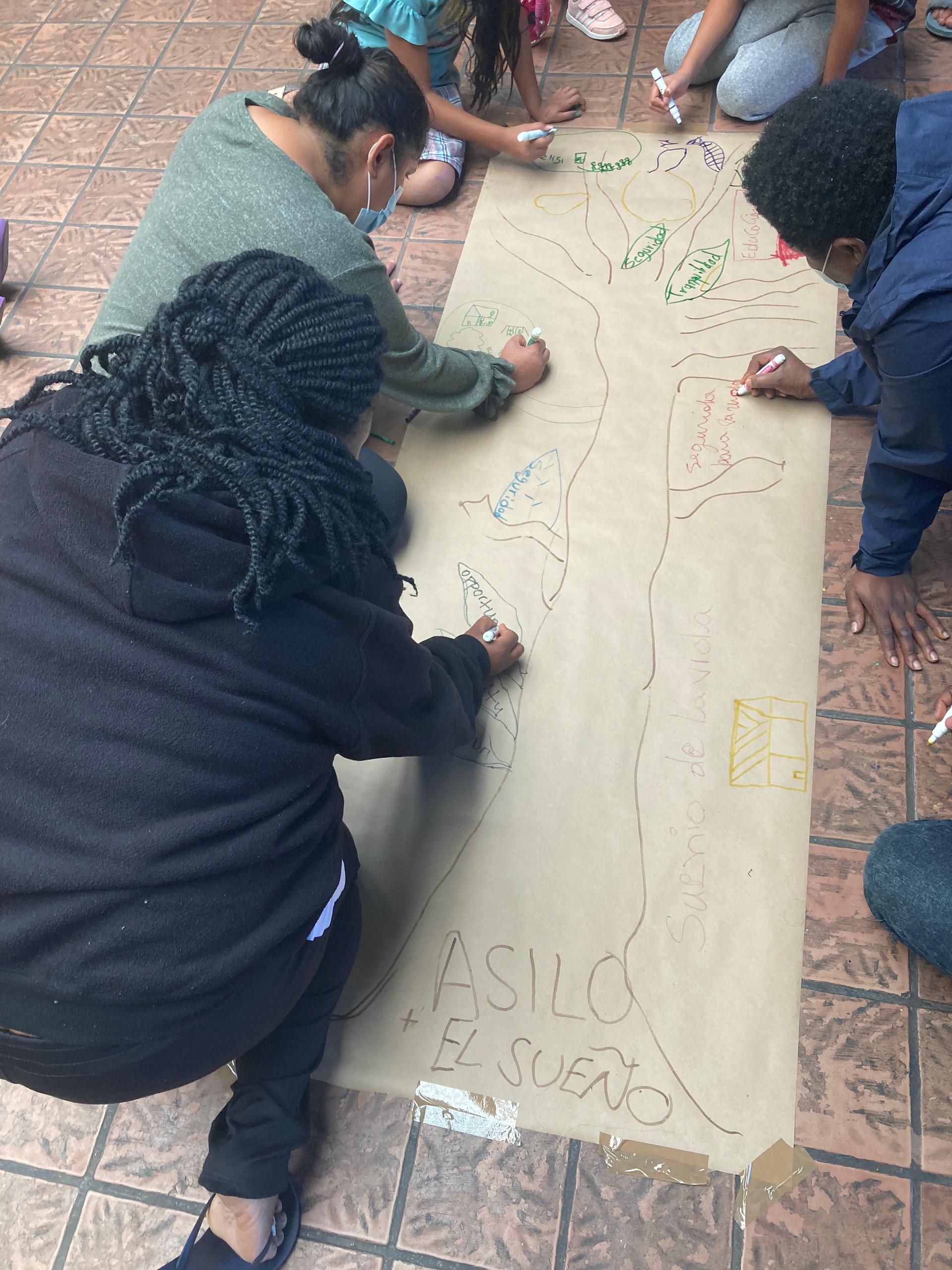

On the same day the border reopened, a group of migrants at the Border Line Crisis Center wrote down on large pieces of paper what faces them on their stunted journey to asylum.

Miedo, “fear.” Odio, “hate.” Tristeza, “sadness.”

And also what they think is on the other side of the border.

Seguridad. “Security.” Oportunidad. “Opportunity.” Tranquilidad. “Tranquility.”

Instead of waiting indefinitely for a chance to enter the US, some migrants are now seeking asylum in Mexico.

Related: A federal jury ruled that a Washington state detention center owes detainees minimum wage

Gilberto Herrera, the Mexican federal government’s delegate to Tijuana, said that the government is working to speed up the asylum process, and streamline getting work permits.

“There are new opportunities for migrants to work in Mexico. From the Tren Maya to reforestation in southern Mexico, there are jobs for people who want them.”

“There are new opportunities for migrants to work in Mexico,” he said. “From the Tren Maya to reforestation in southern Mexico, there are jobs for people who want them.”

Antonio Rodriguez, 21, is an asylum-seeker from Honduras, who also lives in the encampment in Tijuana. He got a work visa and is now employed by a local construction company.

But he still faces danger in Mexico and said that seeking asylum there isn’t an option. He said that he’s been kidnapped multiple times. One time, he said that he watched his kidnappers execute another man right in front of him. He said he’s been abandoned by smugglers in the middle of the desert.

“Mexico isn’t safe for me,” he said.

He said that he prayed to God that after Biden was elected, that he’d end Title 42.

“He made promises to migrants, but he hasn’t kept them,” he said.

Rodriguez said that despite the horrific risks, he’ll stay in Tijuana until the US changes its policies to finally get his asylum claim.