Heba Nabil Iskandarani received her new passport in September after a long process of researching her family’s history and finding documentation.

For most of her life, Heba Iskandarani struggled with her identity. The 26-year-old architecture teacher at Birmingham City University in the United Kingdom always gave the same answer whenever someone asked where she comes from.

She would say that she is half-Lebanese, half-Palestinian, but born and raised in Dubai.

“Then they ask me, ‘What do you hold, like, what’s your passport?’ And I go like, ‘I have no passport right now,’” she told The World.

Both of Iskandarani’s parents were born in Lebanon. Her father’s father was a Palestinian refugee who fled from Jaffa to Lebanon during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Though Iskandarani’s father was born in Lebanon, the Lebanese government considers him a refugee because of his Palestinian origin and would not grant him citizenship. And though Iskandarani’s mother is a Lebanese citizen, her citizenship couldn’t be passed on to Iskandarani because of restrictions in Lebanese law.

So, like many Palestinians, Heba had no official nationality. Her only legal papers were Lebanese “laissez-passer” travel documents commonly issued to refugees or stateless people worldwide.

Iskandarani grew up in Dubai. She says she loves the place, but always lacked a sense of belonging, even as a child.

“I went up to my dad, at [the age of] 11, I still remember,” she recalls. “I should be thinking of cartoons and toys and stuff. And I was like, ‘Dad, I need to move to Canada.’ And he looked at me and was like, ‘What are you on about?’ and I was like, ‘I need a passport, I need a citizenship. Let’s go to Canada.’”

Her parents were less enthusiastic about the idea, but she wouldn’t let it go. At the age of 17, she started digging deeper into her family history. She emailed lawyers and officials. She then applied for citizenship in the United Kingdom and Egypt, but that didn’t work out.

Related: Spain offers citizenship to descendants of Jews forced out during the Inquisition

In Dubai, Iskandarani says, something kept nagging at her. She knew that given her legal status, if something ever happened to her father, she would be forced to move to Lebanon. “I wanted an option to choose what I want to be or go where I want to go,” she says. “I wanted an option. I wanted freedom.”

After completing her bachelor’s degree, Iskandarani was accepted to a graduate program in the UK, hoping that might open the door to British citizenship. She found a good job, and things were looking up. But then the company went bankrupt. She lost her work visa and was forced to return to Dubai, with an unresolved identity crisis.

‘You might be’ Jewish

Four years later, while researching her family origins online, Heba stumbled upon a big surprise. A Google search of her surname, Iskandarani, quickly uncovered that though in Arabic it refers to being “from Alexandria” in Egypt, the name is common among Sephardic Jewish families.

Sepharadim, as they’re called in Hebrew, are Jews who were expelled from Spain and Portugal in the late 15th century, and ended up mostly in Northern Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. For Heba, that family connection was something to explore.

“Baba, no, seriously, it’s true.”

“I went up to my dad and I was like, ‘Dad, look, you might be of Jewish origin’,” she recalls of the surprising discovery. “He looked at me and he was like, ‘No, you must be crazy.’”

Then Iskandarani says she told her father, “Baba, no, seriously, it’s true.”

Further research led Heba to a Spanish law passed in 2015 granting citizenship to the descendants of Sephardic Jews exiled from Spain. This lead started to look very promising.

She also took a DNA test that revealed surprising results. It showed that her father’s side of the family had roots in Europe, with ethnicities that included Portuguese, Spanish, Jewish and North African.

Roger Martínez-Dávila, a historian at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, helped Heba dig deeper into her Sephardic ancestry. He specializes in the medieval history of Jewish “conversos” who converted to Catholicism and was able to trace her family back to a Jewish neighborhood in Barcelona during the Middle Ages.

“For instance, in a Hebrew document dated in May of 1249, a local Jewish court in Barcelona affirmed a Samuel Iskandarani gift of a vineyard as a dowry to his daughter,” Martínez-Dávila said.

While he acknowledges that it’s hard to prove definitively that Heba and her family are direct descendants, what helped track the family was the fact that they kept their surname, Iskandarani. Like many Sephardic Jews, the family converted to Islam, most likely out of self-preservation.

Heba later discovered that her great-grandfather was a Mediterranean trader who settled in Jaffa. So she realized that her ancestors were exiled from Spain for being Jewish, and then, 600 years later, they fled from Jaffa — this time for being Muslim.

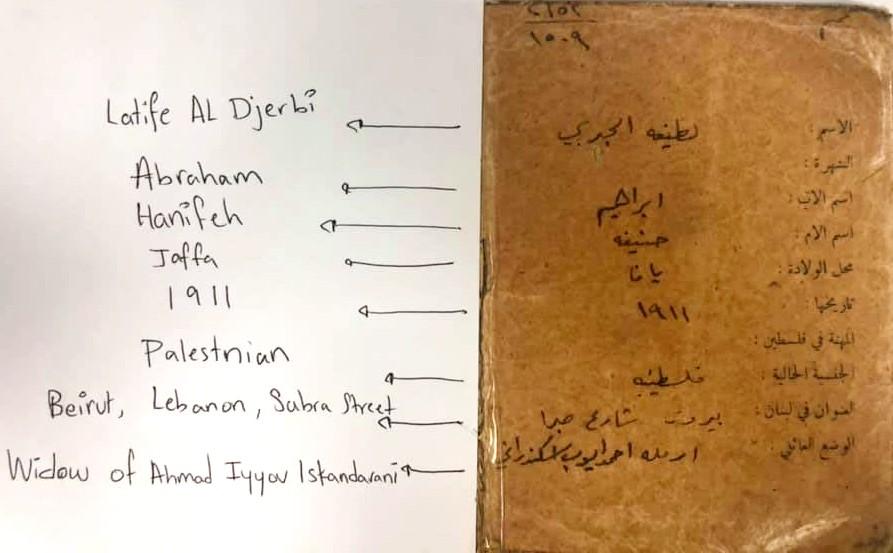

In a cache of family documents, she found an identity card belonging to her great-grandmother, Latife Djerbi, whose name suggests origin from the Tunisian island of Djerba that has a historic Jewish community. She retained some Jewish customs from the holiday of Passover, and many of her family members had Hebrew names such as Moses and Jacob.

“In the case with Heba, what you really kind of appreciate is that it challenges every kind of perception we have about identity, especially religious identity,” says Martínez-Dávila.

Getting a passport

Even before discovering her Jewish roots, Heba was fascinated by Judaism. Subconsciously, she says, she always knew there was something there. When she was 21 years old, she tattooed a famous verse — translated into Arabic — from the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Psalms on her leg.

Translated into English, it reads: “If I forget you, Oh Jerusalem, may my right hand forget her skill. May my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you, if I do not exalt Jerusalem above my chief joy.”

Related: Becoming Portuguese: How Brexit and 500 years of Jewish history changed one British’s singer’s life

In late 2018, Heba presented her family’s case to the Federation of Jewish Communities in Spain to certify her heritage. A few months later, the application was approved. “I was jumping up and down, crying and screaming, and I was like ‘Dad, it worked, it worked’,” she says.

Six months after that, Heba got Spanish citizenship. And last month, she finally received her Spanish passport. She says she feels safe now — and free.

Under the law, more than 150,000 people of Sephardic heritage have landed Spanish passports, and almost one-third are non-Jews.

This week, the first commercial flight from Abu Dhabi landed in Tel Aviv, Israel, following the recent peace agreement signed between Israel and the United Arab Emirates — a deal Heba says she supports. Now she’s waiting for the pandemic to calm down so she can finally visit her grandfather’s birthplace in Jaffa, after entering the Holy Land with her new passport.

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?