In 1795, a ship called theMary departed from Providence, Rhode Island, and headed for cities along the West African coast in what are now the countries of Senegal, Liberia and Ghana.

The following year, the Mary returned to the United States with 142 enslaved men, women and children on board.

Related: 400 years: Slavery’s unresolved history

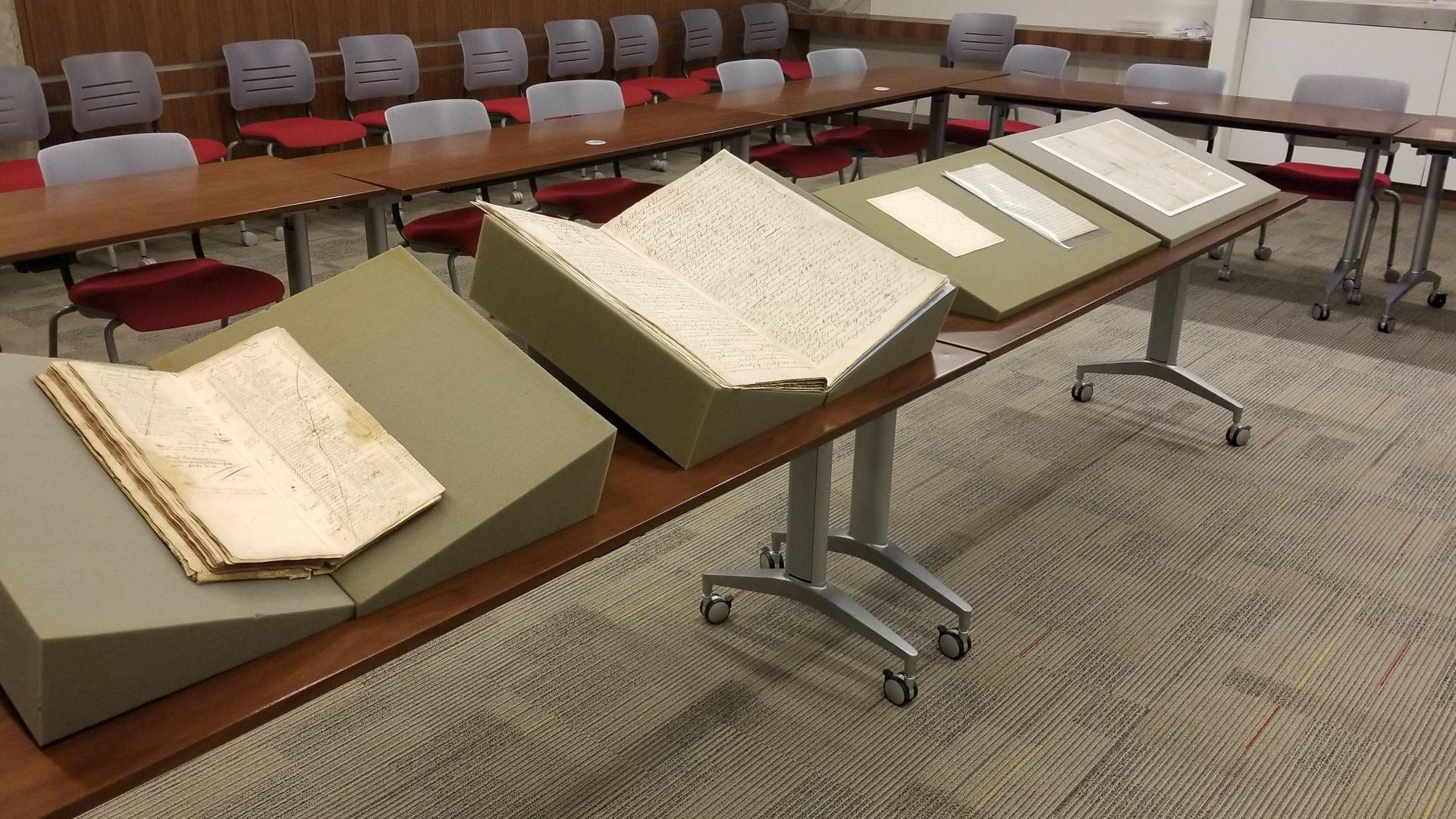

We know this because these details are written down in the ship’s logbook — a book that was recently discovered in a closet in California. It now has a new home at Georgetown University, where it is being preserved by scholars and digitized.

“What’s unusual about this one is the level of detail that is provided day to day,” Adam Rothman, a historian at Georgetown, told The World. The Mary’s log, he added, is particularly rare as it documents a voyage to the United States before Congress abolished the importation of enslaved people in 1807.

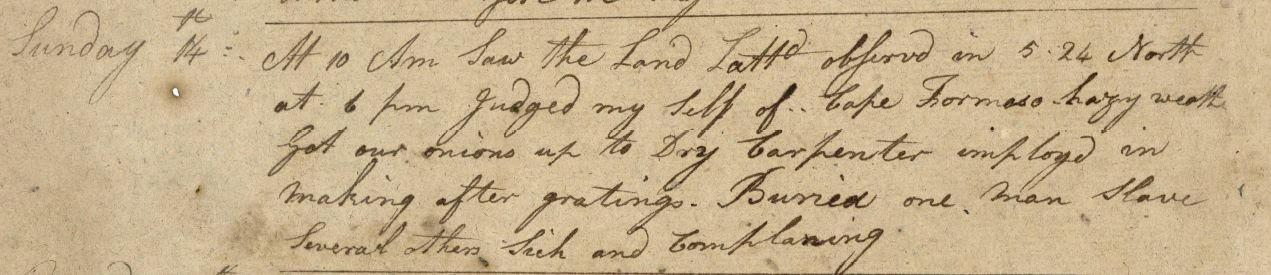

“There’s some standard stuff like what the weather was like, the wind, the currents but then there’s also a record of the transactions that take place on the West African coast, the kinds of goods that are bought and sold in exchange for people — and then this record of death and dying.”

“There’s some standard stuff like what the weather was like, the wind, the currents but then there’s also a record of the transactions that take place on the West African coast, the kinds of goods that are bought and sold in exchange for people — and then this record of death and dying,” Rothman said.

Related: Ghana’s ‘Year of Return’ is emotional for descendants on both sides of the slave trade

Over the course of the Mary’s journey, 38 enslaved people on board died of causes including disease, violence inflicted by the crew, or death by suicide. The detached, clerical accounting for their deaths by the logbook’s unknown author is the only information in the book about the enslaved people on board.

“All it tells us is that they were on board that vessel, and…a shockingly large number of [the enslaved people] died during the middle passage.”

“The book tells us almost nothing about them: It doesn’t tell us their names, it doesn’t tell us where they came from originally, how they got onto the vessel of the Mary. All it tells us is that they were on board that vessel, and … a shockingly large number of them died during the middle passage,” Rothman said.

Related: Retracing a slave route in Ghana, 400 years later

“The way those deaths are recorded in the logbook is probably the most shocking thing about it. All it says, over and over, day after day, is: Boy died, buried at sea … That’s it,” he continued.

The logbook also recounts the story of an attempted uprising by a group of enslaved men on the ship.

“They try to free themselves from the hold of the ship and take over the vessel, but they’re beaten down, gunned down by the crew,” Rothman said.

“It’s narrated in incredible detail in the journal. You can kind of almost see the leader of the rebels emerging from the hold and trying to take over the ship.”

“It’s narrated in incredible detail in the journal. You can kind of almost see the leader of the rebels emerging from the hold and trying to take over the ship,” he added.

The logbook itself has an unusual history; in the early 1930s, parts of it were transcribed and published in a multivolume set of sources on American slavery compiled by scholar Elizabeth Donnan. In the intervening years, Rothman said the book likely stayed in the family of the person who originally wrote it and traveled with them as they moved west to California.

“At Georgetown, we’ve been examining our own history of slavery as an institution very intensely over the last five years … There was a Georgetown student aware of what was going on, [who] knew that a neighbor of his had this logbook in their family, and he basically talked to their neighbor and convinced him to give it to Georgetown so this logbook could be part of the heritage of knowledge about the history of slavery,” he explained.

Related: A professor with Ghanaian roots unearths a slave castle’s history — and her own

Over the last few years, Georgetown University has been probing its own connections with slavery. In 1838, two of the school’s founders used the sale of 272 enslaved people to finance the institution. In 2019, the university announced a plan to raise money to benefit the descendants.

Rothman says preserving artifacts like theMary’slogbook is one part of the work the university must do.

“I think for a university like Georgetown, which is a place of learning, perhaps the most important thing that we can do is to preserve the archival record of this history and explore those archives with the goal of reaching a better understanding of the past and teaching each generation of students at Georgetown not just about what happened in the past, but their own connection to it,” Rothman said.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?