The power of protest: Part I

People attend a Black Lives Matter protest during nationwide unrest following the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, near the Oklahoma State Capitol in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, May 31, 2020.

This analysis was featured in Critical State, a weekly newsletter from The World and Inkstick Media. Subscribe here.

As the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin sparks mass protests around the world, Critical State’s next two editions of Deep Dive focus on recent research about protest movements and their capacity to produce durable change.

Related: World responds to protests sparked by George Floyd’s death

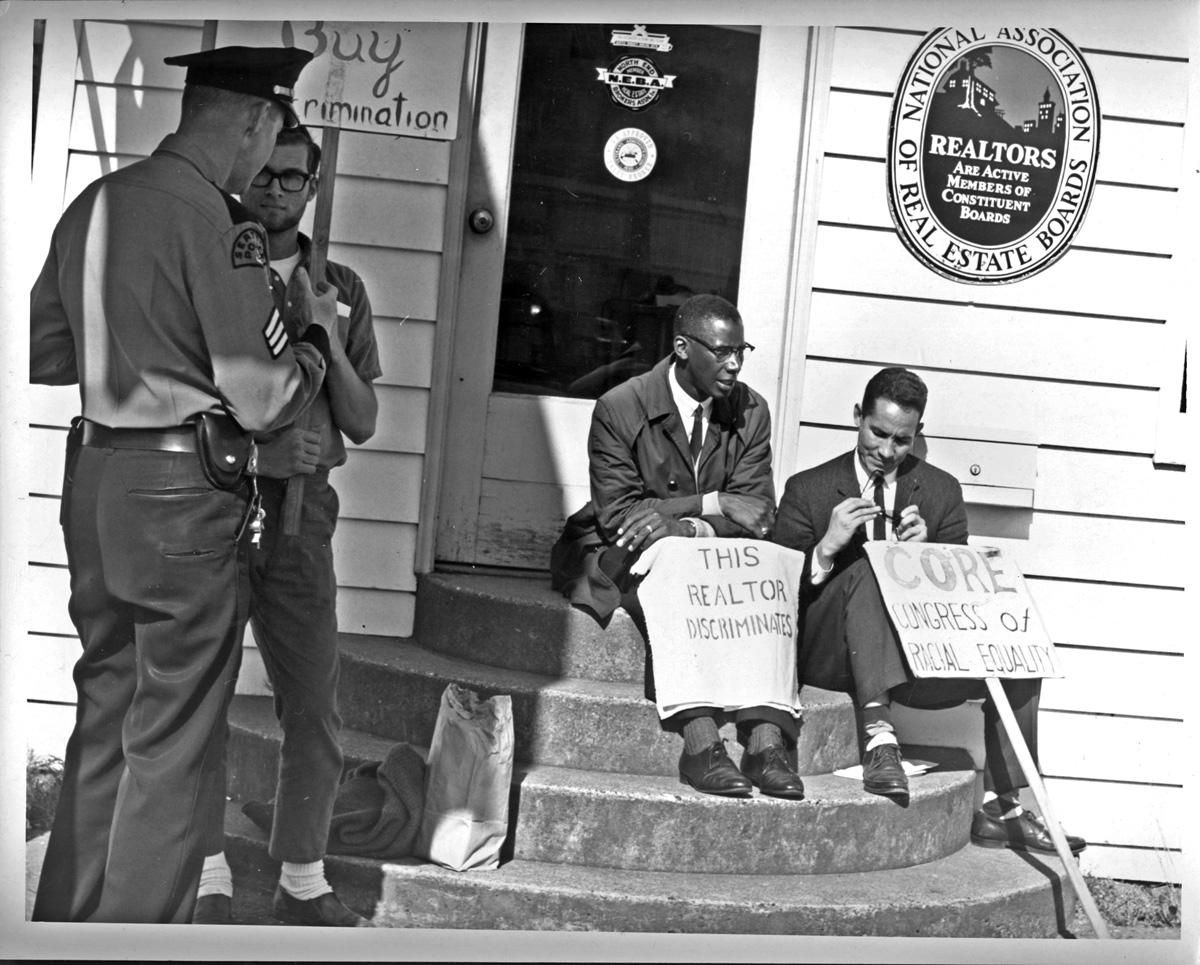

A new article in the American Political Science Review looks at the effect of black-led civil rights protests in the 1960s on voting patterns.

Princeton political scientist Omar Wasow offers a model for thinking about how protest movements make electoral progress through what he calls “agenda seeding.” Wasow posits that protests allow groups that normally have little power to determine what the country cares about, either in politics or in news coverage, to gain temporary control over the agenda.

This power grows when violence breaks out, although the effects change depending on who is seen as primarily responsible for the violence. Even when protests are widespread, few people experience them directly. Instead, mass understanding of protest is typically mediated through what news organizations decide to cover and how they decide to cover it.

Related: Analysis: Who joins rebel armies?

In order to test his theory that agenda-seeding exists and drives voting behavior, Wasow first had to test that protests — and not civil rights-oriented political campaigns — were actually the main drivers of civil rights news coverage in the 1960s.

Drawing from a large database of newspaper articles and polling data, Wasow found that both news headlines and the percentage of the public rating civil rights as the country’s most important problem are much more closely correlated to levels of protest participation than to presidential elections. This suggests that it really is grassroots movements — not elite discourse — that put civil rights on the national agenda in the 1960s.

Related: Tear gas has been banned in warfare. Why do police still use it?

Wasow also found that violence at the protests, whether by police or protesters, made news coverage much more likely.

A protest in which both police and protesters engaged in violence would receive almost three times as much coverage in The New York Times on average than a protest that was non-violent on both sides. Those articles also tend to be longer, doubling in average length depending on whether the protests became violent.

With the role of protest in setting the agenda established, Wasow tried to measure what forms of protest moved the needle in major national elections. He looked at county-level vote share in presidential elections in 1964, 1968 and 1972, and sorted counties by their proximity to protests — one way of measuring their likelihood to experience protests through local media. In counties that were over 90% white — that is, where direct political organizing as a result of civil rights protests was unlikely — Wasow found that being next to a county that had a non-violent civil rights protest increased vote share for Democratic presidential candidates an average of 1.6%.

Related: How ‘cacerolazos’ became a symbol of Colombia’s protest movement

However, when the protests were violent, regardless of police response, white voters responded differently. When neighboring counties experienced violent protests, 90% white counties actually saw roughly 2% dips in Democratic presidential vote share. The same violence that drove press coverage also cut voter support once white voters heard about it, largely through white-run news organizations.

Protest’s power to set agendas is high, it seems, but its power to persuade is limited.

Critical State is your weekly fix of foreign policy without all the stuff you don’t need. It’s top news and accessible analysis for those who want an inside take without all the insider bs. Subscribe here.