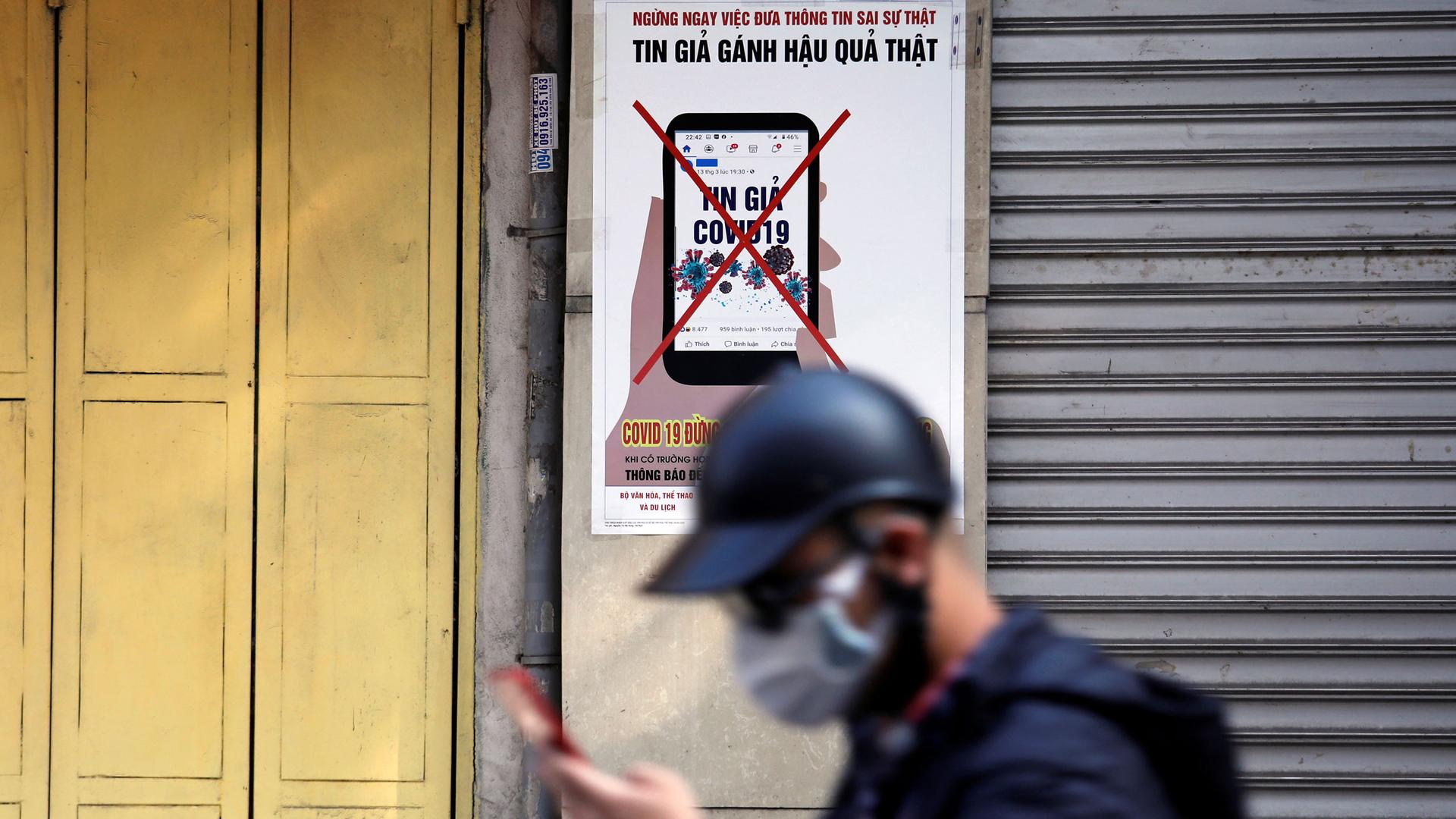

As COVID-19 spreads around the world, so does misinformation — ranging from fake cures to full-blown conspiracy theories about the origins of the virus.

Some countries have imposed fines for spreading “fake news” or rumors about the virus, while other countries are issuing restritctions or fines for information that contradicts official statements.

COVID-19: The latest from The World

Facebook said last week it would start notifying users who had engaged with false posts about COVID-19 that could cause physical harm, such as drinking bleach to cure the virus, and connect them to accurate information. It’s an uncharacteristically aggressive stance by the social media giant, which has been reticent to police fake news in other arenas such as politics.

Misinformation about the novel coronavirus bears some similarities to climate change, says Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive scientist at the University of Bristol. Lewandowsky spoke with The World’s Marco Werman about the best ways to speak to misinformed friends and family and how societies can combat misinformation.

Marco Werman: What are the main types of misinformation circulating about COVID-19 that you’ve been seeing around the world, Stephan?

Stephan Lewandowsky: You can break it down into, on the one hand, just simple misinformation — people getting something wrong and sharing it. The number one misinformation is that COVID-19 is not much worse than the flu, when in fact that’s unfortunately not true. COVID-19 is a far worse virus with a much higher fatality rate. At the other end, we have conspiracy theories and there is a whole bunch of those — mainly about the origin of COVID-19.

Related: Russia is trying to spread a viral disinformation campaign

What’s interesting is you’ve spent part of your career looking at misinformation about climate change. What similarities between misinformation about COVID-19 and climate change are you seeing?

One of the similarities is that, in both cases, the views are politically polarized, at least in the United States. We know from a lot of survey data that in the United States, climate change is denied mainly by people on the political right. We just did a survey last week in the US involving 2,000 respondents and we found precisely the same thing. People on the political right are more dismissive of the risk from COVID than people on the political left.

Related: It’s possible to ‘inoculate’ the mind against climate misinformation, study shows

We know with climate change that fossil fuel companies have sown the seeds of skepticism over the years. Is there any evidence suggesting who’s doing this with misinformation around the coronavirus and who might stand to gain if that is, in fact, happening?

With the coronavirus, it appears as though most of the misinformation comes not from leading political figures, but from the population at large. Only about 20% of the misinformation regarding COVID is issued by opinion leaders and celebrities, and so on. And I know this based on an analysis by the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford, who’ve just published that analysis. However, the 20% of opinion leaders who are providing the misinformation — they receive a lot more engagement on social media. So their influence, despite being in the minority, is nonetheless considerable.

With someone who is misinformed, “you’re wrong” is usually not the best way to open this conversation. What is the best way to talk to someone who is misinformed about COVID or climate, for that matter?

I think, first of all, you have to understand that there are different people and different audiences and you must tailor your message to the audience. … Number one is to underscore the scientific consensus. If you tell people that 97 out of 100 climate scientists agree on the fundamentals of the science, that is sufficient to boost their attitudes toward climate change — a little bit.

Related: How Wikipedia’s volunteer army combats misinformation

I mean, whether we’re talking about COVID-19 or climate change or political candidates, this seems like a much wider endemic problem — the misinformation issue. So in the bigger picture, how do we as a society combat misinformation?

We have to look at the role of the social media platforms and whether they’re exercising their responsibilities. So, for example, it turns out that more than half of all misinformation that was posted on Twitter about COVID is still up there, despite the fact that they’ve been identified by fact-checkers as being incorrect. And for Facebook, that’s 24%, for YouTube, about 27%. So a large share of misinformation that has been identified is still visible on social media. And so, as a society, we just have to ask, well, should the social media platforms be given the latitude to do that? Or should we tell them that they have to live up to their responsibility and deal with misinformation better? With a bit of luck, maybe this crisis is a global reset and people are beginning to recognize again that you need experts to deal with complicated problems and you can’t just have somebody tweeting at a virus to make it disappear. That’s just not gonna work.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Reuters contributed to this report.