With less foreign aid, Thai clinic struggles to serve migrants and refugees from Myanmar

First established over 30 years ago by Dr. Cynthia Maung, Mae Tao Clinic is perhaps the largest and most renowned part of a constellation of community-run organizations serving thousands of migrants and refugees from Myanmar living in and around the Thai city of Mae Sot.

For decades, the sprawling clinic has provided everything from psychiatric care to prosthetics for land mine victims to maternity care. It arose amid the student, pro-democracy movement in Burma in 1988, and the brutal repression by the Burmese regime of that movement, its website states. “Fleeing students who needed medical attention were attended in a small house in Mae Sot,” according to clinic information.

But in recent years, precipitous funding cuts have caused places like Mae Tao Clinic to significantly reduce services, while many other local aid organizations have shut down.

“To reduce some of the costs, we also have to look at some of the services we cannot provide further.”

Dr. Maung estimates that the clinic is operating at 75% of its previous budget now, adding that “to reduce some of the costs, we also have to look at some of the services we cannot provide further … for the referral, we can only contribute a certain amount of the budget or cost because the cost of referral to a higher level is very high. In the past … we could refer all patients who required advanced level care, but right now, we cannot.”

Related: They were CIA-backed Chinese rebels. Now you’re invited to their once-secret hideaway.

Run by a military junta until 2010, Myanmar was largely closed off to outsiders, but the border town of Mae Sot became an epicenter for foreign aid organizations, which provided essential funding and capacity-building for community-based organizations like Mae Tao. SUVs emblazoned with the logos of international nonprofits and government aid organizations were a common sight amid the bustling Burmese markets and tea shops that still make Mae Sot feel more like a Burmese outpost than a town in Thailand.

Naw Annie Po Moo, director of operations at Mae Tao, recalls that back then, “When you needed something, you could get the funding very easily, so you [would] expand based on the need.” The clinic grew to provide everything from maternal care to prosthetics for land mine victims, gaining a reputation that led people to travel from all over Myanmar — not just the nearby border areas — to seek free treatment there.

Related: Fearful of losing power, Thailand’s army opts for democracy lite

But since 2010, when Myanmar ostensibly democratized and opened itself up to foreigners, many of these organizations, including USAID, have shifted their attention — and their funding — away from the border and into Myanmar itself where they could now open new headquarters.

“Government, before, they want to support [the] Burmese community in Burma, let’s say, but they cannot go directly into Burma … If they want to help Burmese people, they have to go through Mae Tao Clinic; now they can access population directly through Burma,” Naw Annie said.

Ellen Somers, who is in charge of fundraising and grants for the clinic, echoes that: “The biggest change in funding happened since political transitions in Burma, such as nationwide ]the] ceasefire agreement and the [National League for Democracy] winning elections,” she said.

Related: Gambian minister brought Myanmar to The Hague ‘in the name of humanity’

Dwindling support for refugees in Myanmar

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which facilitates repatriation of refugees to third countries like the United States, also changed their focus from sending refugees abroad to sending them back into Myanmar, where it was presumed the budding democratic and peace process would create livable conditions.

But, at least on paper, few people have taken up the offer to move back. A recent article in The Sydney Morning Herald reports that, according to one local civil society leader, “The UNHCR had set up a voluntary repatriation centre, but only about 1,000 people had used it over a two-year period.”

Duncan McArthur, Myanmar director for The Border Consortium, the aid organization primarily tasked with managing the refugee camps along Thailand’s side of the border, told The World last year that “It’s still a volatile situation, there certainly has been a significant [decrease] in armed hostilities since 2012, but it’s not a sustainable, peaceful area to return to.”

McArthur said that while TBC’s caseload has been reduced by over one-third because of people being resettled to third countries, moving back to Myanmar, or trying to build a life in Thailand outside the refugee camps, funding has been cut in half. “So, per capita, you know, we’re getting less support now from the international community than we were 10 years ago for refugees,” he said.

Related: In Myanmar, underground poetry nights build bridges between Rohingya and Burmese writers

A report last year from the Transnational Institute, which does international research and advocacy, states that “People living across the border in refugee camps, particularly in Thailand, are increasingly under pressure from authorities on both sides to return to Myanmar regardless of the many risks, while the international community is reducing humanitarian support to the population in these camps.”

Mae Sot: Where refugees help refugees

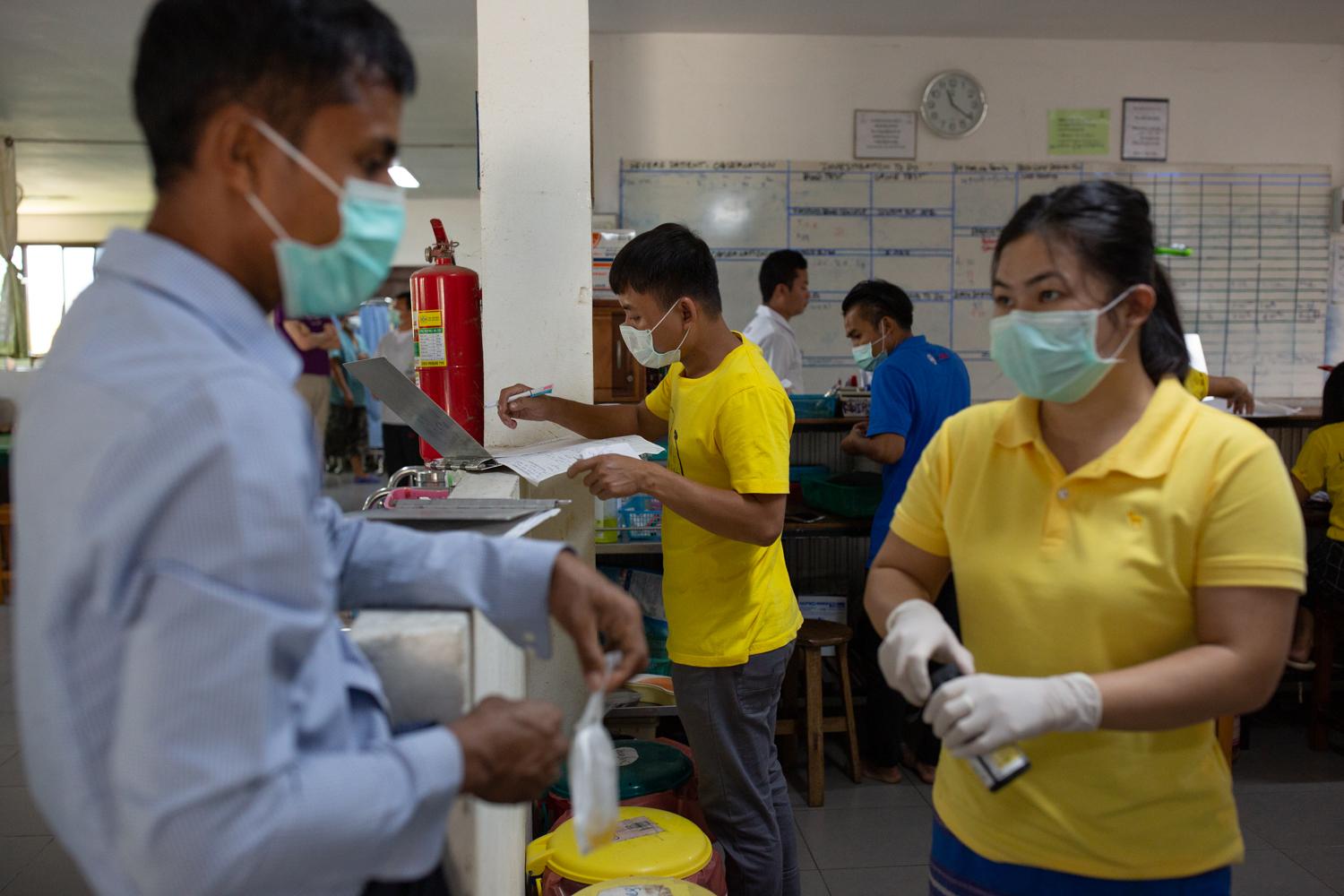

Amid these precarious changes, even as their budgets are cut, the Mae Tao Clinic has managed to remain indispensable to the refugee and migrant community because it is so closely fused with it. While there are two foreign doctors on staff now as clinical consultants, the vast majority of Mae Tao’s staff from the director, Dr. Maung, down to the most basic level medics are themselves refugees and migrants. This gives them a linguistic and cultural competency that neither Western nor Thai doctors could match.

“I decided to go to Mae Tao clinic because I didn’t have too much money at that time. If I go to Thai or Myanmar clinic or hospital I have to pay too much.”

Sa Noo Noo, a 40-year-old teacher from Myanmar, who was temporarily working in Mae Sot, sought free treatment at the clinic for abdominal problems in December 2018. “I decided to go to Mae Tao Clinic because I didn’t have too much money at that time. If I go to Thai or Myanmar clinic or hospital I have to pay too much,” he said.

Also, the clinic has a good reputation: “The reputation of Mae Tao Clinic is they are very patient, kind, careful.”

Related: Facebook wants to create a ‘Supreme Court’ for content moderation. Will it work?

Medics are sourced from local communities on both sides of the border. After six months of basic training, Dr. Maung said they have to spend at least four months working in the field in those same communities before “they can apply to higher-level training like midwife or nurse aid or medics, which requires another 10 months of training.” But she said that the focus now is more on “training the trainers” who can educate and empower people in those communities to manage health care needs there.

Nevertheless, funding remains a major issue. Even as they have started asking for donations for some services, and limiting referrals, Dr. Maung said that only accounts for 7% to 8% of the budget. The core issue is that the clinic is not officially registered in Thailand, since many of its staff are not fully documented or licensed to practice medicine there. This means they cannot accept support directly from institutional funders like USAID, which has such restrictions in place to make sure its money does not end up supporting unregistered activities.

Related: A new report on the Rohingya crisis reveals systemic problems within the UN

“Until 2017, more than half of the funds came through governments. Now, MTC gets more support from foundations. The effects of the change in funding source is that we now work with more donors who each provide smaller grants than the government-funded programs used to do.”

Adapting to new funding models

With both USAID and nonprofits shifting their focus inside Myanmar, the Mae Tao clinic has begun to adapt by seeking out Thai partners to form a legally registered foundation, which can accept institutional funding. Somers said that “Before, Mae Tao Clinic received grants supported by several governments, such as USA, UK, Australia. Until 2017, more than half of the funds came through governments. Now, MTC gets more support from foundations. The effect of the change in funding source is that we now work with more donors who each provide smaller grants than the government-funded programs used to do.”

They’ve also begun to adopt standards and practices to meet the criterion for that funding. Dr. Maung believes this is ultimately a better and more sustainable approach in the long run, compared to relying on international nonprofits as middlemen for support.

“International aid still needs more partnership approach and engagement with the local community organization[s] which [have]has been affected by the war for many years. So, the international NGOs coming through Yangon need to understand the political context and also need to make sure the beneficiary perspective for accessing services … so not only as a recipient, also they are the provider.”

She advised that in Myanmar as well, where these organizations are now building a development infrastructure, they take a new approach that will better prepare local organizations for their departure. “International aid still needs more partnership approach and engagement with the local community organization[s] which [have]has been affected by the war for many years. So, the international NGOs coming through Yangon need to understand the political context and also need to make sure the beneficiary perspective for accessing services … so not only as a recipient, [but] also they are the provider,” she said.