A little over a month ago, Italy was held up as a role model in Europe — an example of a country that had turned itself around following the devastating effects of the coronavirus.

Once the epicenter of the pandemic, the rest of Europe watched in horror as hospitals and crematoriums in northern Italy struggled to cope last March. A harsh lockdown followed, and by the end of the summer, the Mediterranean nation was recording some of the lowest infection rates in Europe.

Then, in just a few weeks, everything changed.

Italy surpassed 1 million confirmed coronavirus infections this week, becoming one of the top 10 worst-affected countries globally. In Naples, COVID-19 patients have received oxygen treatment in their cars as the local hospital is overwhelmed. In Milan, a crematorium stopped accepting bodies of non-residents dying in the city as it could no longer keep up with the death toll. Doctors warn the country could soon face up to 10,000 deaths a month.

So, what went wrong?

Related: Masked and gloved, Italy joins nations creeping out of lockdown

Andrea Crisanti is something of an unlikely celebrity in Italy. The professor of microbiology is an outspoken critic of Italy’s faltering test-and-trace system. When the small, northern town of Vo’ registered Italy’s first death from the coronavirus in February, it was Crisanti who persuaded Veneto regional governor Luca Zaia to test all residents in the town. The results proved what Crisanti had long believed: that the virus could be transmitted even when asymptomatic.

In August, while Italians were returning to normal life, albeit wearing masks and social distancing, Crisanti worried a second wave wasn’t that far off. He wrote to the national government about his concerns but says he was ignored.

“I suggested to the Italian government to take quick action. I presented a plan, but they didn’t answer. Unfortunately, I wasn’t taken seriously enough.”

“I suggested to the Italian government to take quick action. I presented a plan, but they didn’t answer. Unfortunately, I wasn’t taken seriously enough,” Crisanti told The World.

The government’s silence frustrates Crisanti but it doesn’t surprise him. For months, Crisanti and other scientific experts have appealed to Italian authorities to invest in a more robust test-and-trace system. The country should be testing 400,000 people per day, he says. Currently, the figure is closer to 200,000. Instead of investing in health care needs, the government spent €2 billion, or nearly $2.4 billion, refurbishing classrooms, Crisanti says.

“Can you believe it?” the microbiologist asks incredulously. “Two billion euro.”

“If they had invested 2 billion euro in frontline health care,” he says, “we wouldn’t need to wear masks or place additional safety measures in schools.”

Crisanti isn’t alone in his criticism of the Italian government.

Alberto Mingardi, director-general of Istituto Bruno Leoni, a libertarian think tank in Milan, says the government squandered time and money during the summer months when it could have been preparing for the second wave. Mingardi believes the ruling coalition saw the pandemic as an opportunity to increase its role in the Italian economy by renationalizing assets. It financed the resurrection of Alitalia, the national airline, and invested in furlough schemes for private companies, he says. But it failed to address the pressing problems that still existed in the health care system.

Related: Robot nurse helps Italian doctors care for COVID-19 patients

“The government invested much of its political capital to start new endeavors, particularly to nationalize business, but somehow it prioritized that over the management of the pandemic.”

“The government invested much of its political capital to start new endeavors, particularly to nationalize business, but somehow it prioritized that over the management of the pandemic,” Mingardi said.

The government is defending the measures it has taken. Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte conceded last week that there had been mistakes but refused to accept that the government had underestimated the situation. But it may have underestimated public anger.

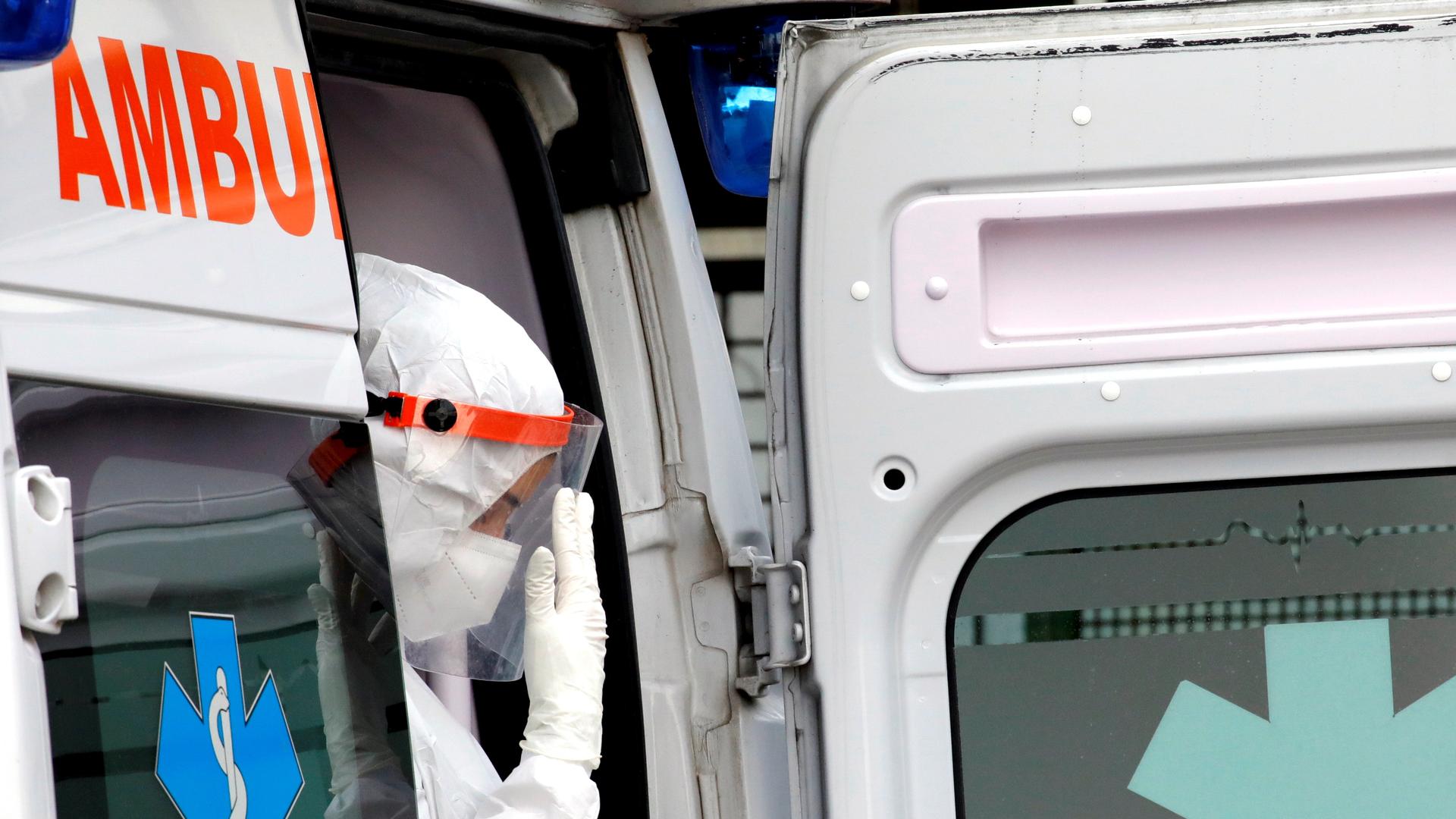

Protests have been held in cities across the country from Milan to Naples against the new coronavirus restrictions. Residents in Milan, in northern Italy, are back under partial lockdown due to the government’s new rules. Conte has divided the country into red, orange and yellow zones, depending on the infection rate and how local health care systems are coping. Lombardy once again finds itself overwhelmed by the virus. Ambulances carrying COVID-19 patients lined up outside hospitals in Milan this week, the region’s capital, unable to access the overflowing emergency rooms.

But it’s not just northern Italy that is under strain. The southern region of Calabria had escaped the worst effects of the pandemic last time around but is now designated as a red zone, too. Neighboring Campania, which includes Naples and the Amalfi coast, has the third-highest infection rate in Italy, but is currently designated yellow.

Related: Doctors in Italy struggle to keep up with COVID-19

The president of the region, Vincenzo De Luca, is not impressed by the system and has appealed for a full national lockdown to be reimposed.

Naples taxi driver Ciro la Motta agrees. He thinks a one-month nationwide lockdown would curb the spread of the disease. La Motta also believes the regional divisions are politically motivated. Designating Naples in Campania yellow means the city must observe a curfew between 11 p.m. and 6 a.m., but bars and restaurants can stay open until 6 p.m. La Motta says not placing Naples into the red zone means the government avoids having to pay out money to furloughed workers.

“I think it’s kind of fake news because this is a way for the government to avoid giving money to all those activities that would otherwise have to be closed in orange or red zones.”

Still, bar owners and restaurateurs in Naples are furious with the soft restrictions they face. Telling a restaurant to close at 6 p.m. is a waste of time in a country where most people eat late, they argue. La Motta says many are now demanding evidence to show that the virus can spread easily in restaurants.

“You must tell me what it means to close at 6 o’clock? This is what the owners of these places say: ‘Have you any study that shows you effectively that inside the restaurant, you can be affected by the virus?’”

The government says the protests are being stoked by far-right groups and the mafia. But la Motta says there’s genuine anger among many workers he meets who are struggling to make ends meet. He estimates his own earnings are down 95% this year.

Prime Minister Conte has vowed not to impose a harsh national lockdown like what took place in the spring. Mingardi, with the Istituto Bruno Leoni, says the government may also face considerable pushback to an all-out lockdown. Italians were largely compliant during the first lockdown, mainly due to a collective fear of the virus and the terrifying news reports coming out of the north of the country. Now, says Mingardi, they are more aware of how the virus spreads and of the government’s failure to improve health systems during the summer months. They may not be so ready to rally around the flag this time around, he adds.

“Alas, most of the stories people listen to these days are related to the inefficiencies of the system and I think it’s rather easy to predict that the lockdown will be far more difficult to enforce now than in the spring.”

With Italy’s coronavirus infection rate once again rising to one of the highest in Europe, it may be more difficult for Prime Minister Conte to keep his promise.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?