Daniel Kanter says his father, David, couldn’t figure out why an infected wound on his leg wouldn’t heal. David had been visiting Daniel in Dallas, Texas, over the Christmas period, and sought out medical care there.

Doctors at the local hospital were baffled as to why David’s white blood cells weren’t fighting the infection.

A few weeks later, test results provided the answer. David had leukemia, and the doctor’s prognosis was bleak.

“They gave him less than three months to live in February. I think he made it about a month,” Daniel said.

Related: Wajahat Ali on maintaining one’s faith through crises

When David, 82, was moved to a hospice, authorities in Texas were debating what steps to take to tackle the novel coronavirus, which was starting to spread in Seattle. Daniel considers himself lucky because he and his mother, Rori, could be at his father’s bedside when he died. His siblings couldn’t travel because of the pandemic.

But the family was not able to hold a funeral for David. Daniel and Rori collected his father’s ashes from the crematorium and took them home. They’re hoping to spread David’s ashes at their family home in Lenox, Massachusetts, later this year.

“We’ll try to gather family and friends around their home in the summer hopefully, and spread my dad under the apple tree where my grandparents are spread,” Daniel said.

Not being allowed to hold gatherings after a death is unsettling for some families. For Daniel, it made his father’s passing seem somewhat unreal. “It feels kind of like it didn’t even happen, you know? With no kind of response except, sort of, in our home storytelling. There’s no crescendo to the death. It happened, and it’s gone. It’s like everyone’s ignoring it.”

Related: Amid lockdown, churches find creative ways to keep in touch with the masses

Sharing stories can be an important part of the grieving process. In rural Ireland, it’s the main feature of the traditional wake. This is when the body of the deceased is laid out in the family home for a day or more. Neighbors and friends stop by to tell stories, sing songs and have a drink or two.

When Betty Ryan died in Ballyferriter, in County Kerry last month, her family knew a wake would be out of the question. But neighbors came up with a plan. They decided to create a guard of honor along the mile-long route from the church to the local graveyard. Ryan’s next-door neighbor Seán Mac an tSíthigh said it was a very emotional moment.

“Everyone came out to line the roads, kept the 2-meter social distance apart and it was quite a poignant event,” he said.

Mac an tSíthigh, who’s a journalist, says the local community likes to take ownership of the grieving process as a way to help the bereaved family. Being stopped from doing so evokes traumatic memories from the past.

“There’s a strong folk memory of the famine,” he said, referencing the Great Potato Famine in Ireland caused by a potato blight. “In the 1840s, you know, you had mass deaths at the time, the disease was rife. And that would have been possibly the last time that families were prevented from giving their loved ones a dignified burial.”

Related: Buddhist nun recommends calming the mind to cope with pandemic

Other rituals have also been stopped. Family members are no longer allowed to shoulder the coffin into the graveyard and the custom of mourners filling the grave alongside family members has been banned. Mac an tSíthigh says that tradition provided comfort to the families.

“Gradually, as the grave is being filled, you can hear the hum of conversation just starting around the graveyard and you know, it becomes a lighter moment,” he said. “You can hear laughter as people start to reminisce and tell stories about the person who was just being buried.”

Most religions are dealing with changing funeral rituals right now, and technology is playing a part. The Jewish custom of sitting Shiva, a period of up to seven days where friends and neighbors visit mourners in their home, is now often conducted via Zoom.

Londoner Steven Lewis, whose mother, Ruth, died March 19, was told by his local rabbi that his mother’s funeral would have to happen entirely outdoors. Usually, he said, he would have expected up to 500 people to attend. That day there were only 30. Lewis’ nephew in Australia suggested they film the funeral live on Facebook. Lewis said the experience felt a little surreal, but it was also comforting to know so many people were there with them, albeit virtually.

Related: For this year’s Passover Seder, to Zoom or not to Zoom?

“There’s a Jewish word called a mitzvah, which is like a blessing. So it was a blessing, that people could actually watch it.”

“There’s a Jewish word called a mitzvah, which is like a blessing. So, it was a blessing, that people could actually watch it,” Lewis said. “It made me feel good.”

The funeral was over in 20 minutes, and no one came back to the house to accompany the family. In the end, this was a relief for Lewis. A few hours later, he was struck down with a bad cough and a fever and was bedridden for 14 days. He wasn’t tested for the coronavirus but assumes, that’s what it was. Lewis is planning to sit shiva for his mum in six months’ time — when everyone can come and visit.

For some grieving families, the changes to the rituals are proving heartbreaking. Hasina Zaman, founder of Compassionate Funerals in East London, says her phone hasn’t stopped ringing for four weeks. She provides services for all religions, including the large local Muslim community. Islamic tradition states that a person should be buried within 24 hours of their death. But Zaman says authorities and cemeteries are struggling to keep up with the number of fatalities, and burials are being delayed for seven to 10 days. The families, she says, are distraught.

“People are crying on the phone. They’re in, deep, deep shock.”

“People are crying on the phone. They’re in deep, deep shock. They say, you know, I need to bury my dad right now,” Zaman said.

One key Islamic tradition is the ritual washing of the deceased’s body before burial. Some Muslim leaders are now recommending that this ritual is changed to a dry cleansing practice. Zaman says it’s hard to explain the change to distressed families.

“They’re upset because they can’t do that last performance. You know, that’s the last duty they have to give to their loved one and they’re worried what it means if they don’t carry it out.”

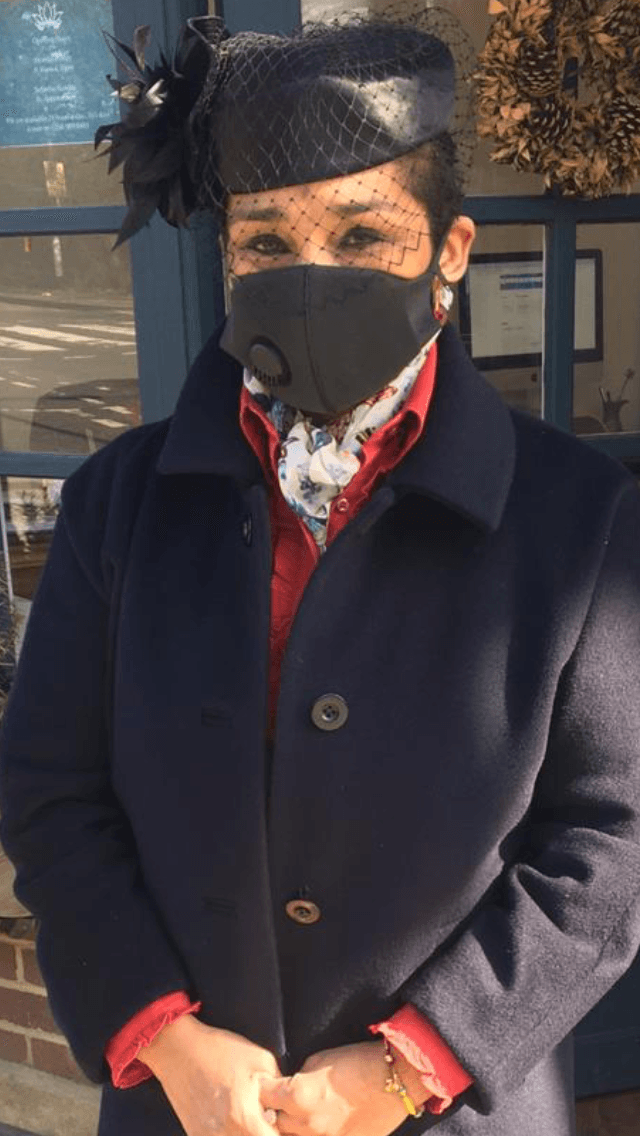

Zaman wears a face mask and protective clothing as much as possible when she works. She has four children and a grandchild but says she is not afraid of becoming ill or even of death. But her family was furious when she decided to continue working.

“They were really, really angry with me, and saying that, you know, you can potentially kill us.”

Zaman says she told them she would take all the necessary precautions, but that by doing her job, she believes she will help a lot more people than by going into isolation. Her family has since come around and Zaman says now they couldn’t be more supportive.

“Now they’ve got a household chore list and when I come home from work, there’s always a meal prepared for me, so I can relax a little in the evening.”

Daniel in Texas is providing support to his mother, who can’t travel back home to Massachusetts just yet, and to the wider community, as well. Daniel is the senior minister of First Unitarian Church in Dallas. He’s hoping his own experience of grief will counsel him on how to help others get through this challenging time. Daniel says he finds solace in the words of C.S. Lewis, who wrote about grief following the death of his wife, just four years after marriage.

C.S. Lewis reminds us that grief can feel like fear, but we must learn to be patient with ourselves too: “What he’s saying to us is walk a little more softly on your path, be a little more gentle with each other, be a little more honest with your feelings and with others.”