This surrealist graphic novel delves into architecture and social change

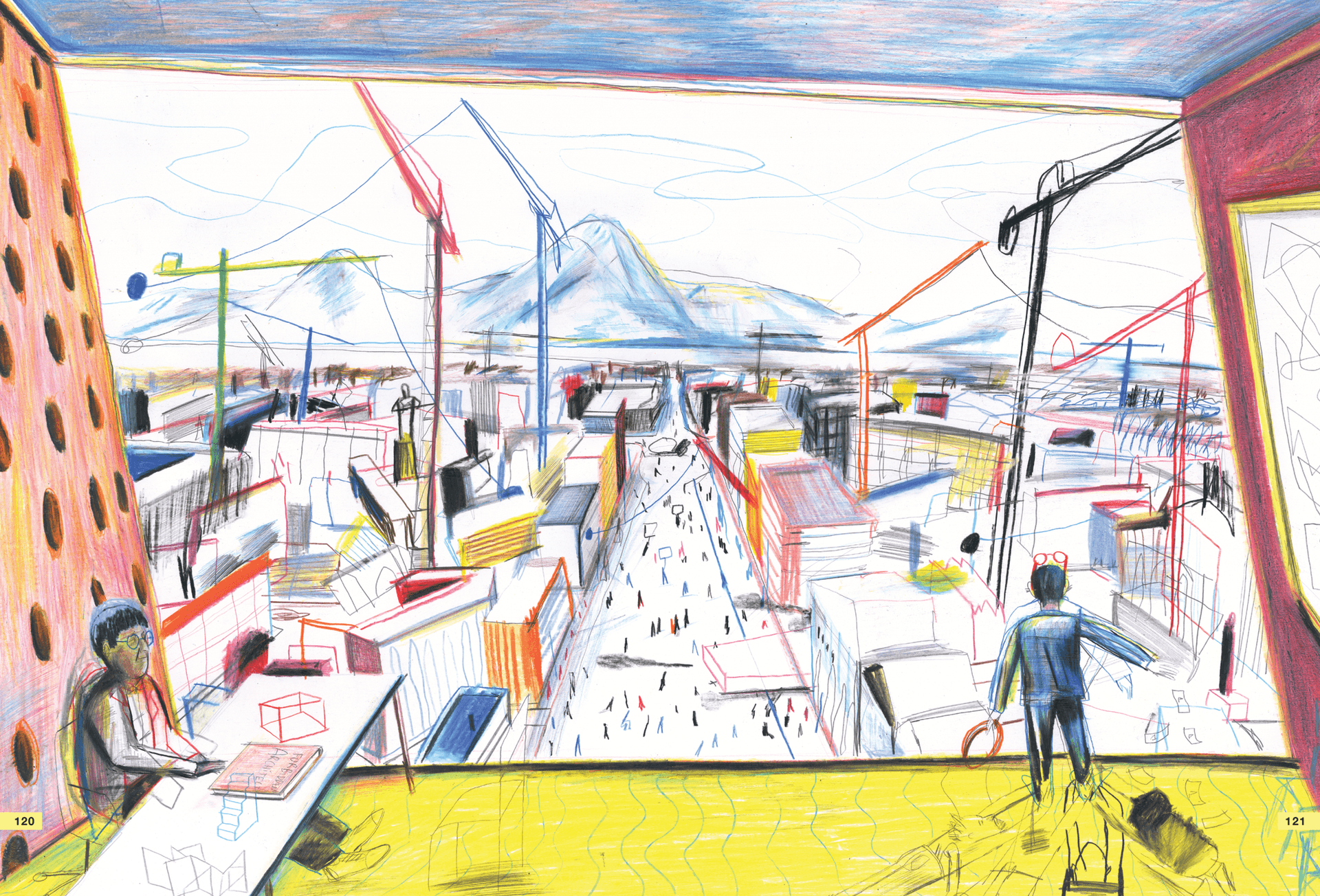

A page from Viken Berberian’s “The Structure is Rotten, Comrade,” illustrated by Yann Kebbi.

Around the world, ongoing protests are signaling people’s desire for change — in leadership, equality and basic human rights.

Protests and change are central points in Viken Berberian’s latest satirical graphic novel, “The Structure is Rotten, Comrade.” The book, set primarily in Armenia, explores the connections between culture, memory and architecture. It satirizes Soviet-era Communism and buildings and follows an architect’s quest, alongside his father, to transform Yerevan into a city of high-rises — but they are met with resistance.

The World’s Carol Hills spoke to Berberian about the inspiration behind the book and its relevance after Armenia’s Velvet Revolution of 2018.

Carol Hills: This book is satirical and funny. I’m wondering what you’re commenting on specifically with this work?

Viken Berberian: I was just drawn to architecture as a trope, as a theme, and I admit I have a soft spot for cement like [the main character] Frunz. But with Frunz, there are many despicable things about him. I think what motivates him and certainly his father, who is a builder, is money. They’re very much open to the idea of demolishing the beautiful historic homes in this city to make way for this urbanization and to profit from it.

You started writing this book years before the revolution in Armenia in 2018 took place. What was your response to that? What did you think when that happened?

Of course, we started to write the book before the revolution, but it sort of all came together after. There’s certainly this unambiguous message in the title, “The Structure is Rotten, Comrade.” Obviously, we’re quite aware of political corruption, of corporate greed and what was happening here until we had this Velvet Revolution in 2018 that upended the era of the oligarchs.

Now, for our listeners who obviously can’t see the book, the illustrations by French illustrator Yann Kebbi are very colorful and animated. It’s like hundreds of colored pencils scribbled across the pages. I wonder why you decided on this style.

We both did not want to be constrained by genre or tradition. The illustrations are revolutionary in form and content. He breaks many of the classical codes of comics, the traditional talk bubbles and the dialogue. For example, our book does not have borders or frontiers, and Yann really knows how to capture comedy and pathos in a way that’s not judgmental.

You and the illustrator Yann Kebbi started writing this book five years ago. Since then, there’s been a lot of protests. The world is going through lots of upheaval. Do you view the book differently than you did when you started it?

No, the book is what it is, and I’ve always watched the protests and I continue to watch the protests with consternation. Unfortunately, we don’t see the same results. This movement towards more open societies in other parts of the world — I’m hopeful that that will change, and I’m hoping that the millennials, our kids, your kids, will be a part of that process. So that’s why we actually reference “The Little Prince” in our book, too, towards the end of the book, in the form of a graffiti on one of the walls. I think the reason why the little prince is there is because we often forget kids in the larger discourse, and we dismiss them, but we should actually hear them out.

This interview has been edited and condensed.