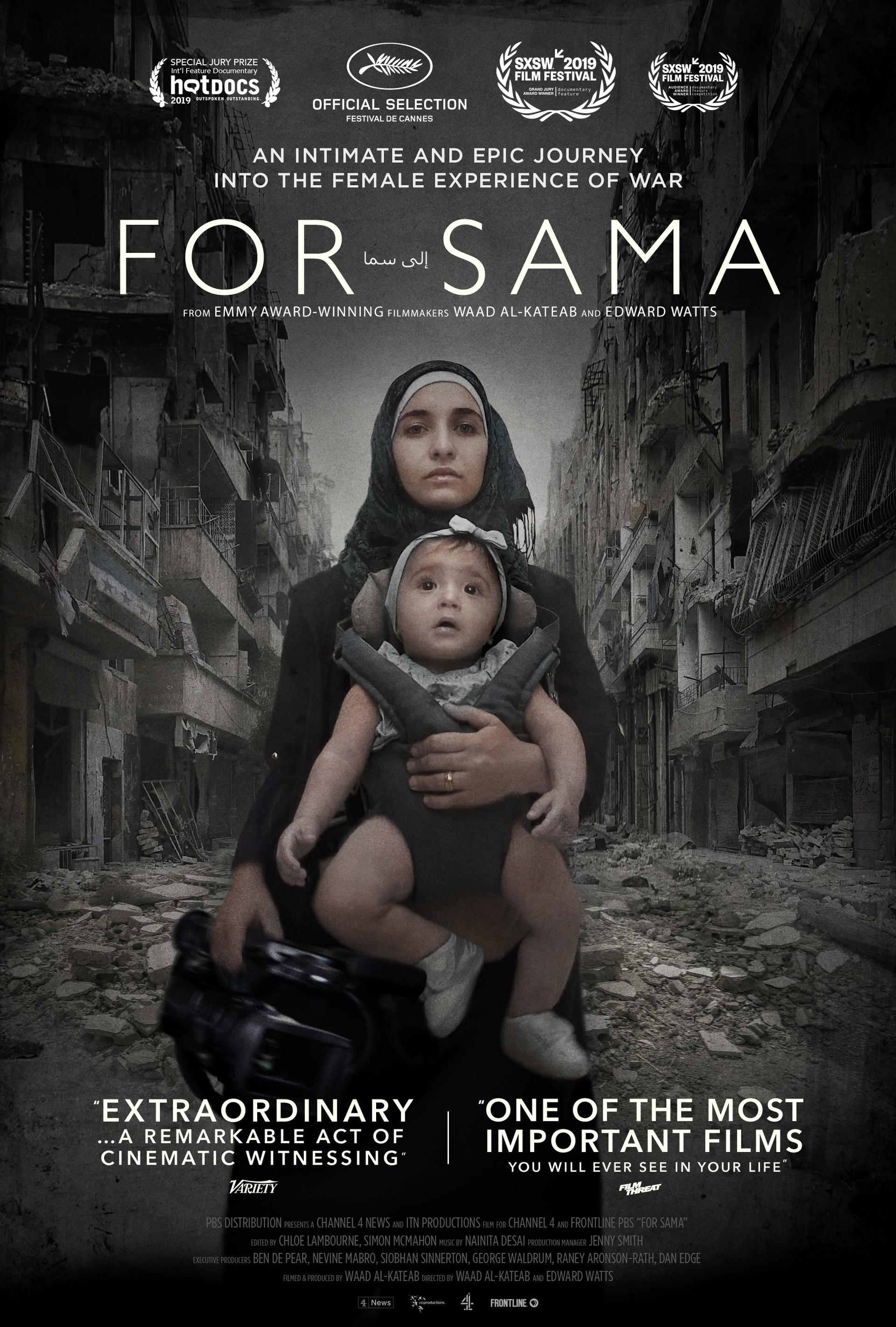

‘For Sama’: A love letter from filmmaker to daughter on life and war in Aleppo

Hamza al-Kateab (left) and Waad al-Kateab (right) with their daughter, Sama. Waad al-Kateab is the filmmaker of “For Sama,” a documentary about life in the bisieged city of Aleppo, Syria.

Imagine, just for a minute, living inside a war zone. Going to work every day, caring for your family, trying to be normal in a situation that is anything but normal. That was the experience of filmmaker Waad al-Kateab and her husband, Hamza, a doctor, who made the decision to stay in the besieged city of Aleppo, Syria.

Related: After 8 years of war, one Syrian says ‘we really just wanted freedom’

Waad al-Kateab decided to film her own life in Aleppo constantly for five years, in which she fell in love, married a doctor, gave birth, and survived the months-long siege, airstrikes and snipers, while living in an upper floor of the last hospital in the city.

Related: Torn apart by the Syrian war, these siblings struggle to stay connected across 6 different countries

Kateab and her husband, Hamza, spoke with The World’s host Marco Werman about why they stayed in Aleppo, and what they hope their daughter, now two years old, will one day understand about their ordeal and survival in the Syrian civil war.

As the film opens, Waad al-Kateab sings to her daughter, Sama.

Marco Werman: After the singing, you hear an explosion in a hospital in Aleppo. Tell us about that scene. What was happening?

Waad al-Kateab: So, it was just a normal day when I was sitting with my baby in the room playing together. And you start [to] hear the aircrafts flying over. And then they started the explosion far [away], [and then] closer, closer, closer.

Immerse us deeper in the city of Aleppo in this time. What does it look like when all this violence, all these attacks are happening?

It looks like a very beautiful city — whatever happened. But with all this beauty and the great people who were just trying to stay alive every day. There [were] more than 300,000 people who were living in [a] besieged city. The hospital was targeted, the civil defense centers were targets, schools were targets, normal people [and] places were targets. So, [it was] just a struggle to stay alive, [a] struggle to challenge the regime, the Russians who are bombing this area and keep your life normal as much as you can.

Tell me about daily life as you’re trying to struggle for normalcy. What you do for food? Where do you get money? Where did you get diapers?

Before the siege, everything was available because of the trade between Turkey and Syria. So you can find everything you want in Aleppo, any kind of fruit or food. But then, when the siege happened and the Assad regime and Russian forces controlled … Aleppo, all the fruit, vegetables — anything fresh, you can’t find it.

There’s an incredible scene where one of the women in the house that you’re focused on gets a persimmon. And it’s like she’s just received a diamond.

Exactly.

Hamza, you ran the hospital. For you, as a doctor and a new father, what was your daily routine like and how hard was it for you to balance the atrocities you had to deal with in the hospital? You said 6,000 patients came through while you were there. And meanwhile, Sama, your daughter — not to mention Waad, your wife — is exposed upstairs to the shelling and the bombs.

I can’t really understand mentally how we got through all of this. But you feel like you have to do what you have to do. When there is a massacre, I can’t think about anything else. It’s just focusing on the casualties at the moment. The most horrifying thing [is knowing that] we are the target of the Russian and Syrian regimes. Everyone in Aleppo knew that. Some patients … [refused] to be admitted at the hospital, even if they needed [an operation]. When they [were] awake, they’re just like, “Take us out of here, please.”

They knew they would be targeted.

Exactly. Like, our chances are better if we are at home or even close to the frontline, because we know that the regime and the Russians will target the hospital.

Throughout all this tension and misery in the film, there are scenes of really joyful moments. There’s a flashback to the day you actually set up the hospital and your friends are really energized and they’re laughing. They’re happy. What was that day like?

Hamza and his friends — the other doctors and some nurses —decided they [needed] to set up a place … people needed to know where [there’s a] hospital. I was not responsible for anything. I was just going around filming them while they were trying to do [it].

You filmed everything. I mean, you had 500 hours of videotape out of this documentary.

Yeah. For me, it was really something I needed to do because I was seeing them doing this great, amazing job.

There’s another joyful moment, of course, when you become a couple, you get married. We see your wedding. What was that day like?

That was one of the craziest days of our life. I remember that day and I can’t be happy enough. We really [tried] our best to find a way to stay alive in that area. And [one way] was to make a small wedding with 15 of our friends. I borrowed [a] dress from my friend. She was just married three months before that. [It was] a very simple wedding of just people trying to be happy.

One thing about your film that was kind of a revelation to me was just the determination of people like you to stay in Aleppo — to not leave.

Hamza: Basically, it became an act of resilience. The Russians and the regime didn’t want to [only] break the armed opposition. They wanted to break the people’s will. So, everyone who was living there knew, “This is my act of resilience and I’m living here.” … Even the car mechanics [would say], “Hey, I’m helping everyone to stay here because I’m repairing their cars.”

Waad: But for many reasons: Hamza is a doctor and any doctor … would make a difference in this situation. I had the camera. I [had] a lot of responsibility to continue filming these people, people who we lived with for five years, who we struggled together [with] in many, many different situations.

Hamza: There are so many families, thousands of families. So we decided, we will be part of this community. And as a family, we’ll be there together.

At the end of the day, this film is a letter of sorts from you to your daughter, Sama. It is titled, “For Sama.” You say at times in the film that you feel terrible for the world that you brought her into. How do you think she will react when she’s old enough to really absorb what you’re telling her in this movie?

Waad: I’m really trying not to put any expectation about this. I will keep her free to express anything she will feel. I need to let Sama watch it every two or three years, how she [will] see [it] when she [will] be 15 or 20 or 25. I’m so interested to hear from her.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.