Love, friendship, protest: 3 former East Germans reflect on the fall of the Berlin Wall 30 years later

East German citizens climb the Berlin Wall at the Brandenburg Gate after the opening of the border was announced early Nov. 9, 1989.

The fall of the Berlin Wall happened 30 years ago on Saturday, Nov. 9. It was a big deal — one of the bookends to the Cold War.

The Wall had separated East and West Berlin since 1961 and basically penned in East Germans, whose government was then allied with the Soviet Union.

East Germans couldn’t travel (without express permission). They had no political freedom, their media was state-run, and the Stasi — the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) state security service — was legendary for spying on East Germans by using their fellow citizens to spy on each other.

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 was a historic moment for East Germans with a “before” and “after” that resonates 30 years later.

The World’s Carol Hills asked three former East Germans to recall how it all went down.

Related: No regrets: East Germans recall attempts to escape Communist state

Gabi Hayes: ‘I wanted to keep everything quiet’

At the time, frustration was growing in East Germany and protests were happening almost every week. But Gabi Hayes was focused on something else: The American she’d fallen in love with. His name was Mark.

Hayes and a group of friends had been hitchhiking one day after their bus broke down. They were trying to get home to Jena, the university town where Hayes lived. So they stuck out their thumbs.

“And there was this van that stopped. It had a Western license plate … it was the first time that I had met an American in my life.”

Mark, the American, was traveling around East Germany in a rented van with a friend. He and Hayes connected. It was 1985.

A long-distance romance ensued with Mark visiting Hayes whenever he could, because, of course, she wasn’t allowed to leave East Germany to visit him.

By early October 1989, Hayes had applied for an exit visa to leave East Germany and move to the United States to be with Mark.

For Hayes, protesting wasn’t an option. She was still waiting for her visa to be with Mark.

“I was afraid because I was in a relationship with an American,” she said, adding, “So, I wanted to keep everything quiet.”

But things were moving quickly. On Oct. 17, East German President Erich Honecker was forced to resign. And it was around that same time that Hayes learned that her exit visa had been approved.

“They said you are allowed now to leave. Here’s your passport…you have two days to get out.”

So, on Oct. 20, Hayes and Mark left East Germany, going through checkpoints, eventually to a new life in the US.

Hayes heard the news in Dallas, where she was just getting settled with Mark. “We were driving down the street…And embraced for a long time and said, we are free and I just couldn’t believe it.”

It’s been 30 years and Hayes has lived in the United States for all of that time, but she still feels personally and culturally East German.

She thinks it’s important to understand what East Germany was, to reckon with it and validate the experience of those who lived through it.

“We valued friendships very much because we were all in the same boat… in East Germany that had a high value.”

“We valued friendships very much because we were all in the same boat… in East Germany that had a high value,” she said. However, she added, “There’s nothing from East Germany, nothing from that time that I want to experience now.”

“I still feel that I am East German…before the wall came down.” She still has family in what was East Germany. Some of her family have done well since the GDR ended. Others have struggled.

Related: Women in Germany’s east earn close to what men do. Can we thank socialism for that?

Siegbart Schefke: ‘What do we do now?’

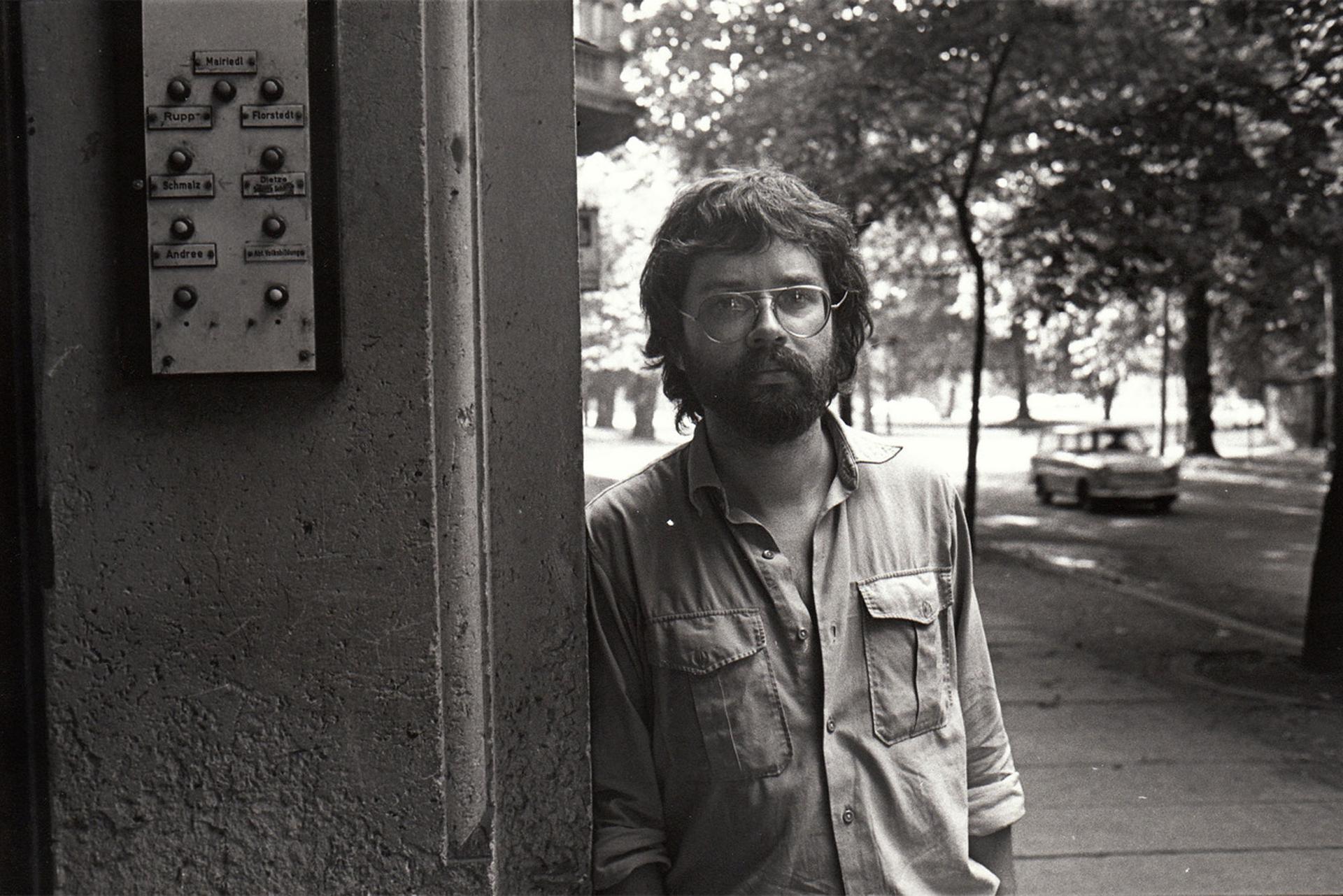

East German Siegbart Schefke, known as Siggi, was a leader of anti-goverment protests. East Germany’s notorious Stasi kept a close eye on him.

He hated the East German State, hated the fact that he couldn’t travel, that there was zero political freedom, that their currency was worthless, that there was no reliable media. The divided Germany also affected him personally.

“For me, the wall not only divided the country into East and West Germany, but it also divided my family. It divided me from my father’s siblings and my grandparents who lived in West Germany. I had never been to West Germany and so, I always wanted to be rid of this wall. That was my goal and that’s, in the end, why I risked so much.”

“For me, the wall not only divided the country into East and West Germany, but it also divided my family. It divided me from my father’s siblings and my grandparents who lived in West Germany. I had never been to West Germany and so, I always wanted to be rid of this wall. That was my goal and that’s, in the end, why I risked so much.”

Schefke remembers the 40th anniversary of East Germany. It was Oct. 7, 1989. The government had planned big celebrations. Mikhail Gorbachev was the guest of honor.

But he came with a message that the East German leadership didn’t want to hear. Speaking to a reporter, the Soviet leader urged the East German government to open up.

That night, East Germans massed in downtown Berlin to protest. A thousand people were arrested. That gave Schefke an idea. He decided he was going to film the next protest.

“And I knew that I [was] virtually the only person who would have a video camera and the only one who would record [the protest].”

And so two days later, on Oct. 9, Schefke went up to the top of a church tower in Leipzig and filmed, as 70,000 East Germans took part in a peaceful candlelit demonstration.

“And [I knew] these recordings must make it to West Berlin and [onto TV in West Germany] straightaway, because 95% — nearly every person living in the GDR — could watch [West German] TV.”

Schefke smuggled the film to West Berlin and it aired.

Fourteen days later, on Nov. 9, an East German government spokesman made a fateful mistake at a press conference in East Berlin. He suggested it was now OK for East Germans to travel outside the country.

When an Italian reporter asked, “Starting when?” The answer was: “As I understand it, ‘Without delay, starting now.’”

Schefke heard it on the radio and a short time later he and his friend Aram walked to the checkpoint at Bornholmer Strasse. They were the first to show up to see if the East German guards would let them through to West Berlin.

“There, we stepped out and spoke with the border control officer. Twenty times we said, ‘We want to go to the West. We want to go now, right this second, to the West.’ And after something like 20 minutes, he placed a stamp in our East German IDs.”

Schefke said it was a rainy cold evening and he turned to his friend Aram and asked, “what do we do now?”

They were afraid they might be shot by border guards. They weren’t sure what was going to happen.

They started to walk across the border into West Berlin.

“So, after 5 minutes or so of walking, we came upon a Mercedes Taxi, and I said, ‘We must be in the West. We’re now in the West because that’s a Mercedes.’”

Schefke and his friend were the first East Germans to freely cross that checkpoint. Hundreds of thousands would follow over the next several days.

Schefke remembers that once he realized he was safely in West Berlin, he partied for five days.

Schefke says he has zero interest in reliving, understanding or assessing what East Germany was. He hated East Germany and everything it stood for.

He said living in East Germany was like living in bondage because of the lack of basic individual rights. And so three decades on, he’s not surprised that it’s been so difficult for people from the East.

“Ask a Korean what the difference between the two Koreas is. The difference is one lives in bondage and the other lives under a democracy.”

“Ask a Korean what the difference between the two Koreas is. The difference is one lives in bondage and the other lives under a democracy. Bondage in the sense of imprisonment, suppression, no freedom of movement, and no press freedom.”

Schefke has gotten very used to freedom. The Wall has now been down for 30 years, longer than it was ever up. Schefke is not looking back.

Andreas Voight: ‘What does it mean to you?’

By October 1989, Andreas Voight was 36, married, with a daughter and he was a filmmaker employed by the East German government.

But he worked in the documentary unit, which was somewhat independent.

His job was to document the life of East Germans of all kinds, to illustrate how they lived. On paper, his government documentary unit was to celebrate and show the lives of ordinary Germans, workers, farmers, to illustrate the socialist project that East Germany was supposed to be all about.

His first film for the government-run documentary unit was about a worker named Alfred. Voight filmed all the places where Alfred spent his daily life, his work, his family.

Related: Vintage home movies show another side of life in East Germany

But by early October 1989, ordinary Germans were protesting the East German government. Voight was shocked.

Even though he technically worked for the East German government, Voight supported the protesters in East Germany and had desperately wanted change and reform.

He asked his supervisors for permission to document the next protest and he was a bit surprised when they said yes.

So, on Oct. 16, Voight and his team filmed in Leipzig as 120,000 East Germans demonstrated against their government. The camera crew threaded their way among the protesters. Crowds of East Germans were yelling “We are the people!”

In the film you see Voight say to a protester: “We’re from the East German government documentary unit: Why are you here at this demonstration? What does it mean to you?”

And the protester said: “It’s time things change in this country, we need free and fair elections, freedom of speech, freedom of travel, freedom to work.”