Most witches are women, because witch hunts were all about persecuting the powerless

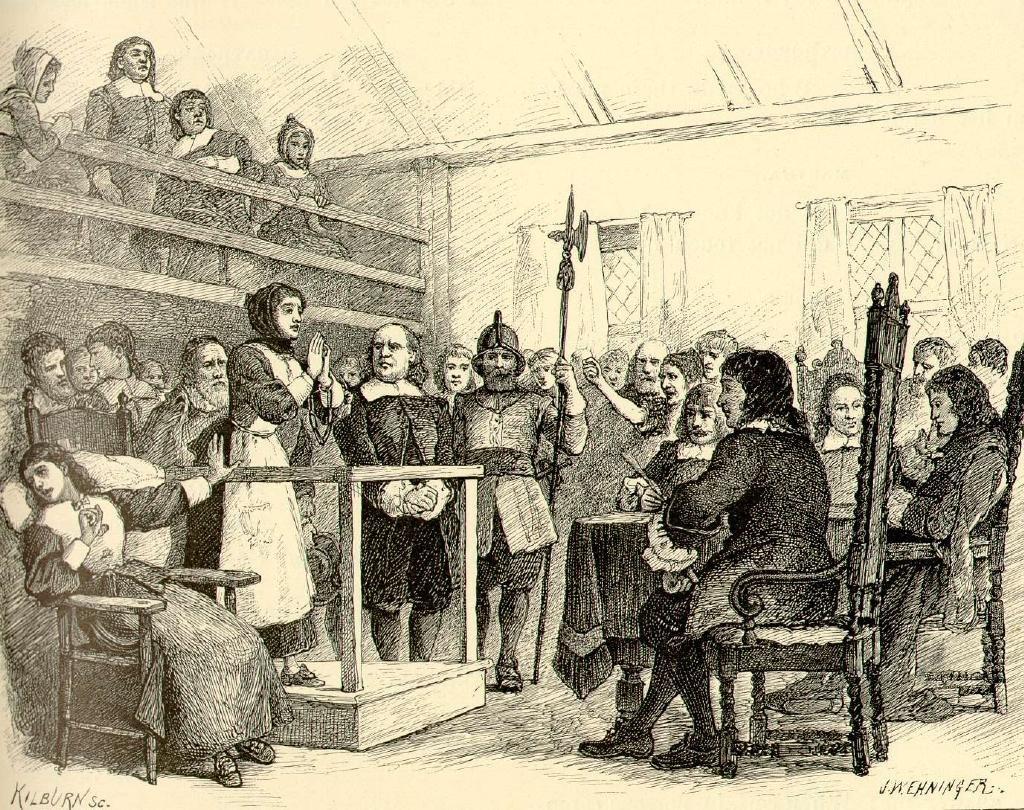

A black-and-white portion from the painting “Witch Hill (The Salem Martyr),” circa 1869.

“Witch hunt” — it’s a refrain used to deride everything from impeachment inquiries and sexual assault investigations to allegations of corruption.

When powerful men cry witch, they’re generally not talking about green-faced women wearing pointy hats. They are, presumably, referring to the Salem witch trials, when 19 people in 17th-century Massachusetts were executed on charges of witchcraft.

Using “witch hunt” to decry purportedly baseless allegations, however, reflects a misunderstanding of American history. Witch trials didn’t target the powerful. They persecuted society’s most marginal members — particularly women.

Too rich, too poor, too female

In my scholarship on the darker aspects of US culture, I’ve researched and written about numerous witch trials. I teach a college course here in Massachusetts that explores this perennially popular but frequently misinterpreted period in New England history.

Perhaps the most salient point about witch trials, students quickly come to see, is gender. In Salem, 14 of the 19 people found guilty of and executed for witchcraft during that cataclysmic year of 1692 were women.

Across New England, where witch trials occurred somewhat regularly from 1638 until 1725, women vastly outnumbered men in the ranks of the accused and executed. According to author Carol F. Karlsen’s “The Devil in the Shape of a Woman,” 78% of 344 alleged witches in New England were female.

And even when men faced allegations of witchcraft, it was typically because they were somehow associated with accused women. As historian John Demos has established, the few Puritan men tried for witchcraft were mostly the husbands or brothers of alleged female witches.

Women held a precarious, mostly powerless position within the deeply religious Puritan community.

The Puritans thought women should have babies, raise children, manage household life and model Christian subservience to their husbands. Recalling Eve and her sinful apple, Puritans also believed that women were more likely to be tempted by the Devil.

Powerless people

As magistrates, judges and clergy, men enforced the rules of this early American society.

When women stepped outside their prescribed roles, they became targets. Too much wealth might reflect sinful gains. Too little money demonstrated bad character. Too many children could indicate a deal with a devil. Having too few children was suspicious, too.

Mary Webster of Hadley, Massachusetts, was married without children and relied on neighborly charity to survive. Apparently, Webster was not meek and grateful enough for the alms she received: She developed a reputation for being unpleasant.

Webster’s neighbors accused her of witchcraft in 1683, when she was around 60 years old, claiming she worked with the devil to bewitch local livestock. Boston’s Court of Assistants, which presided over cases of witchcraft, declared her not guilty.

Then, a few months after the verdict, one of Webster’s upstanding neighbors, Philip Smith, fell ill. Distraught residents blamed Webster and attempted to hang her, supposedly to relieve Smith’s torments.

Smith died anyway. Webster, however, survived the attempted execution — much to the terror of her neighbors, I imagine.

The accused witch Mary Bliss Parsons, of Northampton, Massachusetts, was the opposite of Webster. She was the wife of the wealthiest man in town and the mother of nine healthy children.

But neighbors found Parsons to be a “woman of forcible speech and domineering ways,” historian James Russell Trumbull wrote in his 1898 history of Northampton. In 1674 she was charged with witchcraft.

Parsons, too, was acquitted. Eventually, continuing witchcraft rumors forced the Parsons family to resettle in Boston.

Stay in line, woman

Prior to Salem, most witchcraft trials in New England resulted in acquittal. According to Demos, of the 93 documented witch trials that happened before Salem, 16 “witches” were executed.

But the accused rarely went unpunished.

In his 2005 book “Escaping Salem,” Richard Godbeer examines the case of two Connecticut women — Elizabeth Clawson of Stamford and Mercy Disborough of Fairfield — accused of bewitching a servant girl named Kate Branch.

Both women were “confident and determined, ready to express their opinions and to stand their ground when crossed.” Clawson was found not guilty after spending five months in jail. Disborough remained imprisoned for almost a year until she was acquitted.

Both had to pay the fines and fees related to their imprisonment.

Woman vs. woman

Most Puritans who claimed to be victims of witchcraft were also female.

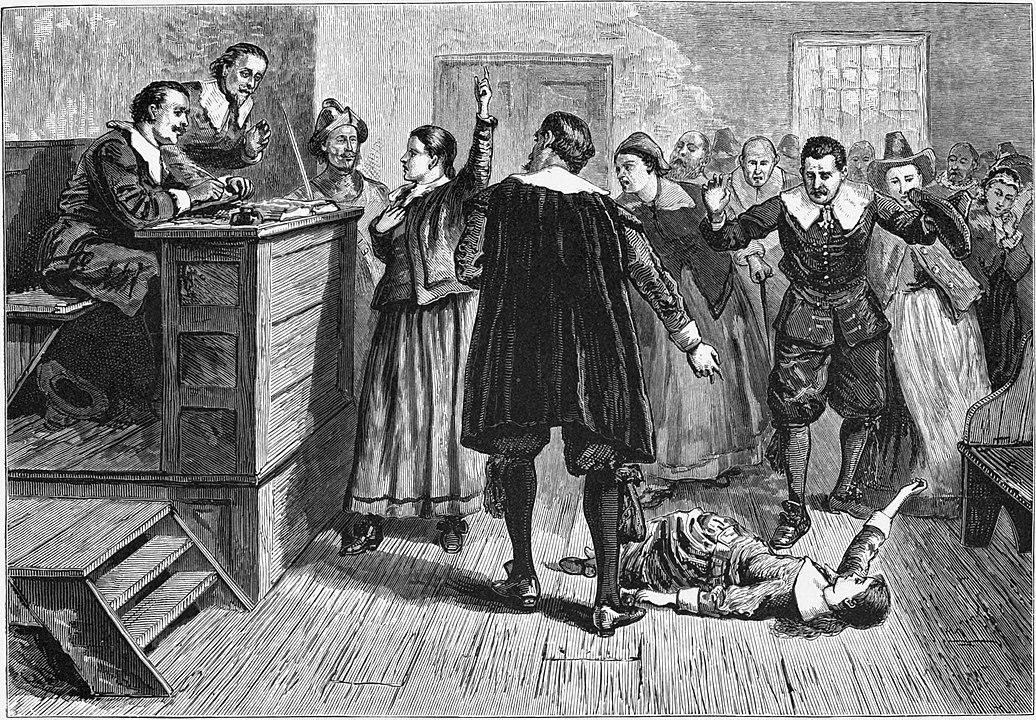

In the famed Salem witch trials, the people “afflicted” by an unexplained “distemper” in 1692 were all teenaged girls.

Initially, two girls from the Reverend Samuel Parris’ household claimed they were being bitten, pinched and pricked by invisible specters. Soon other girls reported similar feelings. Some threw fits, crying out that they saw terrifying specters.

Some have suggested that the girls were faking their symptoms. In a 1700 book, Boston merchant and historian Robert Calef called them “vile varlets.”

Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible” also casts one of the Salem girls as the villain. His play depicts Abigail — who was, in real life, a girl of 11 — as a manipulative 16-year-old carrying on an affair with a married man. To get his wife out of the way, Abigail makes witchcraft accusations.

Nothing in the historical record suggests an affair. But Miller’s play is so widely staged that countless Americans know only this version of events.

Systematic oppression

Other Salem stories blame Tituba, an enslaved woman in the household of the Reverend Samuel Parris, for teaching witchcraft to the local girls. Tituba confessed to “signing the devil’s book” in 1692, confirming Puritans’ worst fears that the devil was actively recruiting.

But given her position as an enslaved person and a woman of color, it’s almost certain that Tituba’s confession was coerced.

This is why witch trials weren’t just about accusations that today seem baseless. They were also about a justice system that escalated local grievances to capital offenses and targeted a subjugated minority.

Women were both the victims and the accused in this terrible American history, casualties of a society created and controlled by powerful men.

Bridget Marshall, Associate Professor of English, University of Massachusetts Lowell

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.