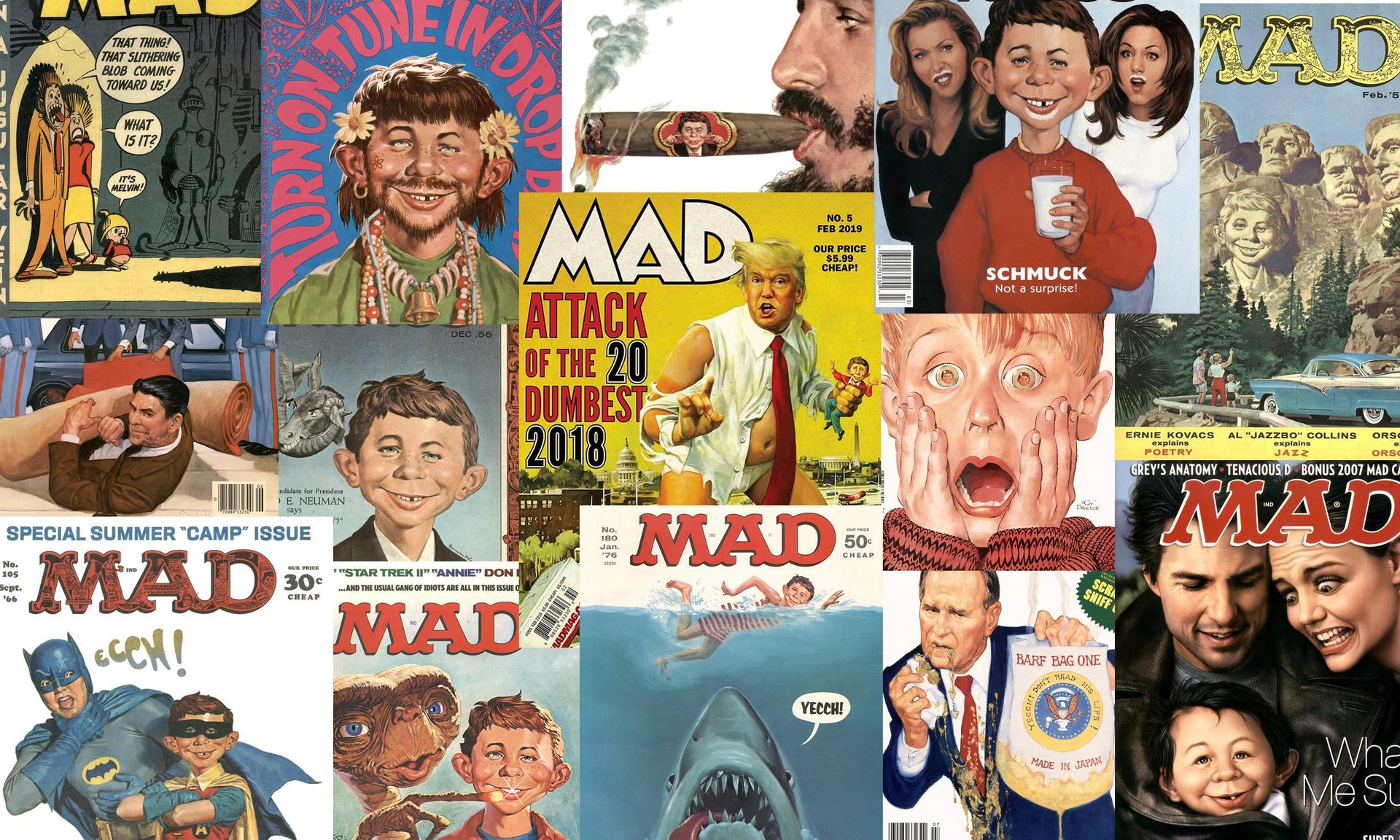

American Icons: ‘Mad Magazine’

Mad for “Mad.”

After a 67-year run, “the usual gang of idiots” will no longer be serving up the snark. After the August 2019 issue of “Mad Magazine,” old material will be reprinted with new covers, but you won’t find any new parodies or cartoons in those pages, aside from the occasional one-off or special feature. It really is the end of an era.

In 1954, a US Senate subcommittee investigating juvenile delinquency called William Gaines, publisher of the successful EC Comics, to testify. “You think it does the children a lot of good to read these things?” asked the subcommittee’s counsel. “I don’t think it does them a bit of good, sir, but I don’t think it does them a bit of harm, either,” Gaines said.

Before Congress could take action, comics publishers decided to regulate themselves. They adopted the Code of the Comics Association, which sharply limited violence, kissing and other fun stuff in comics. To get around these strictures, Gaines turned “Mad Comics” — which parodied other comic books — into “Mad Magazine.” Harvey Kurtzman, the editor, “starts mining all of American culture,” says Maria Reidelbach, the author of “Completely Mad: A History of the Comic Book and Magazine.” Movies, television, books, even Broadway shows that kids probably hadn’t seen — all became fair game to “Mad” writers.

That juvenile, subversive undercutting of the adult world was tremendously influential for the kids who became the counterculture. In his book “The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage,” sociologist Todd Gitlin wrote, “’Mad’ pulled the plug and said, ‘”The Lone Ranger,” Wonder Bread, and TV commercials — even Marlon Brando — are ridiculous!’”

Yet in mocking so much of the adult world, “Mad” was also slyly educational. Longtime writer Arnie Kogen says, “I never aimed anything at kids. I just wrote what I thought was funny. If kids got it, they got it. If they didn’t get it, that was their problem.” On one page, “Mad” would parody TV shows, and would be talking about Soviet politics on the next. In 1963, they ran a parody of West Side Story’s “Jet Song” called “When You’re a Red.”

Roger Ebert credited the “Mad” movie parodies with teaching him to watch with a critical eye. “’Mad’’s parodies made me aware of the machine inside the skin — of the way a movie might look original on the outside, while inside it was just recycling the same old dumb formulas,” Ebert wrote in his forward to “Mad About the Movies.”

By this point, several generations of comedy writers have been reared on “Mad Magazine,” and its influence extends to shows like “South Park,” “The Daily Show” and “The Simpsons,” which has explicitly paid tribute to “Mad.” Even Matthew Weiner, the creator of “Mad Men,” has cited “Mad” as an inspiration. The magazine’s parody of Madison Avenue gave Weiner his first look at a “drunken, callow, glib, self-serving ad man,” as he wrote in the book “Inside Mad.”

The “Mad” sensibility shaped today’s culture of clever, snide sarcasm — the ubiquitous style we call snark. Todd Gitlin says, “’Mad ‘won. ‘Mad’ is now the dominant culture. Today, being unserious is the premium posture.” But even a comedy writer (and son of a “Mad” pioneer) like Jay Kogen sees a downside to this victory. “It supports the idea that it’s better to be cynical than to really feel something,” Kogen reflects. “I’ve been much more ready to pick something apart and to make fun of it rather than to just enjoy it.”

“I don’t think that until I had a child was I able to appreciate that there is such a thing as innocent joy,” Kogen adds. “There’s something to be said for sincerity.”

American Icons is made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

(Originally aired July 25, 2014)

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?