Hollywood’s Stonewall missteps

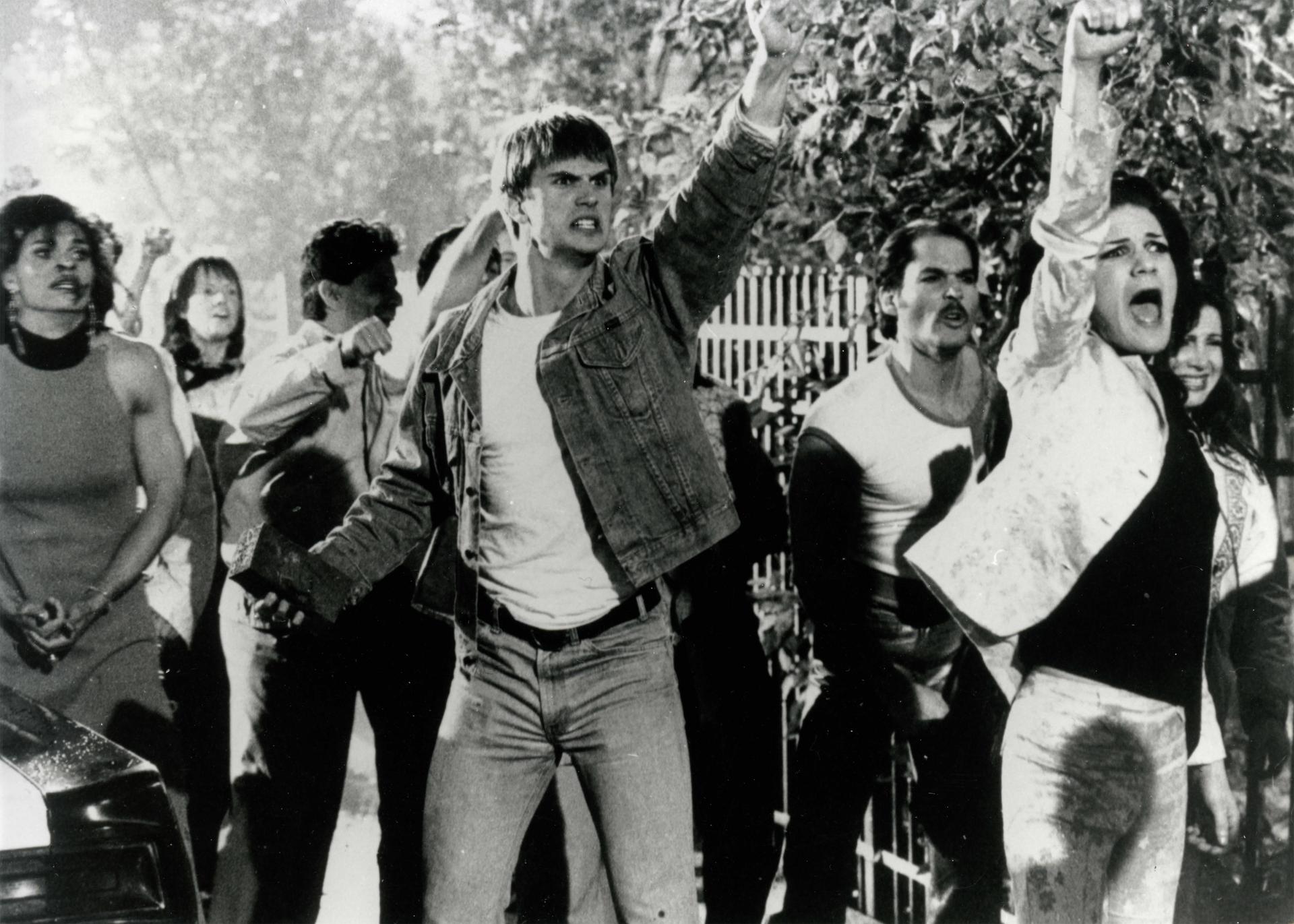

The 2015 movie “Stonewall,” directed by Roland Emmerich.

This month marks the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, the riot that many consider to be the beginning of the modern gay liberation movement. It’s a key moment in LGBT history that’s been fictionalized more than once — but the Stonewall we see on screen doesn’t necessarily resemble the real event.

The best-known depictions of Stonewall come from two films released decades apart — and both called “Stonewall.” According to IndieWire critic Jude Dry, the earlier movie is actually the more nuanced one: director Nigel Finch’s “Stonewall,” from 1995, offers a sympathetic, three-dimensional portrait of the trans women who led the movement and allows its characters to forge meaningful relationships, in contrast to Roland Emmerich’s more retrograde approach to sex and sexuality in 2015.

But both foreground white, male, stereotypically masculine protagonists — and make some of the most pernicious myths about the uprising, like the role of Judy Garland’s death, even harder to dispel.

These features have taken on outsized importance in part because they’re the only ones we have. “Up until very recently, and still, queer film struggled to get made,” Dry says. “As a culture, we don’t have a lot of onscreen representations of our history.”

Mark Segal participated in the riots was he was just 18 years old. Today, he works as an activist and journalist covering LGBT issues — and he’s unimpressed with the way Hollywood has handled the night that changed his life.

“Stonewall isn’t recalled as Stonewall was,” Segal says. “The myth has now taken over, and the real magic of Stonewall is totally missing.”

Both Segal and Dry are hopeful that future depictions of that history will be more honest about what happened before, during and after the riot — and show the heroes of the movement as they really were.

“Any Stonewall film, and any portrayal of our history, shouldn’t dwell in it how hard it was and how horrible everyone’s lives were and how much violence there was,” Dry says. “While that is and was a reality of being gay, and it’s important that young people understand that — that we honor the struggle — I think any film about the gay rights struggle has to be celebratory.”

Segal agrees, calling the “depressing” tone of the films about the riots “another myth,” and emphasizing that he and the others who participated were “happy warriors.”

“For many of us who were there, or created gay liberation from the ashes of Stonewall, it seemed to gradually become historic,” he says. “For us, it was just a regular night out — with a little extra spirit, shall we say.”

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?