Thousands of mixed-race British babies were born in World War II — and adoption by their black American fathers was blocked

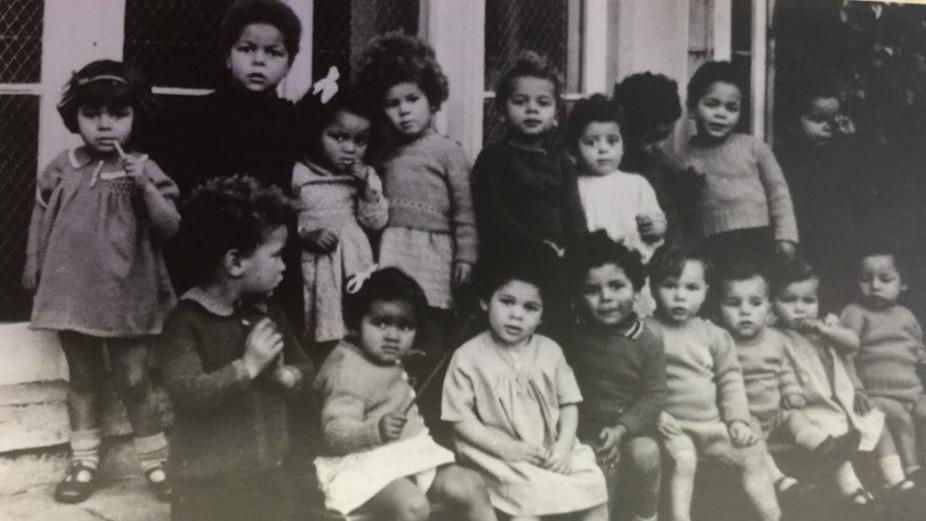

Outside Holnicote House children’s home, Somerset, England.

Around 2.2% of the population of England and Wales is now mixed race and 3.3% are from black ethnic groups. During World War II, over 70 years ago, these figures were far lower. And so, unsurprisingly, life was difficult for the 2,000 or so mixed race babies who were born in World War II to black American GIs and white British women.

They grew up in predominately white localities and experienced significant racism. I have interviewed 45 of these children (now in their seventies), hailing from all over England. Their story of institutional racism rivals the horrors of the appalling story of the Windrush generation.

Related: Britain apologizes for ‘appalling’ treatment of ‘Windrush generation’ migrants

Of the 3 million US servicemen that passed through Britain in the period 1942-45, approximately 8% were African American. The GIs were part of a segregated army and they bought their segregation policies with them, designating towns near to American bases “black” or “white” and segregating pubs and dances along color lines, with dances held for black GIs one evening and whites the next.

Related: US adoption system discriminates against darker-skinned children

Inevitably, relationships formed between the black GIs and local women and some resulted in what the African American press referred to as “brown babies.” All these children were born illegitimate because the American white commanding officers refused black GIs permission to marry, the rationale being that back in the US, 30 of the then 48 states had anti-miscegenation laws.

The children grew up in predominately white areas — the sites where the GIs had been largely based: south and southwest England, South Wales, East Anglia and Lancashire, where they had little or no black or mixed-race role models. Most suffered racism, the stigma of illegitimacy and a confused identity.

Monica, one of the women I interviewed, remembers that there were no other mixed-race children in her area at all. “That was the hardest part,” she told me. “People literally would turn around if I walked into a shop and stare, it was horrible. … I was made to feel like a complete outcast, like I was contaminated.”

Jennifer, meanwhile, recalls one particular incident:

There was a girl that were very friendly. She told me where she lived and I went to call for her one night. And her mother opened the door. Oh, she went bananas. Oh, she went mad! I thought she were gonna have the door off the hinges. It’s a good job my fingers weren’t in the door, she’d have broke them!

Racist name-calling was widespread for these children. Gillian, for example, who grew up in Rugeley, Staffordshire, told me that in addition to “blackie” and “nigger,” when she got to secondary school her peers started to call her “Gillywog.”

The thing that Deborah, born in Somerset in 1945, never got used to was being pointed at in shops. She remembers that children used to ask: “Mummy, why is that girl black?” The hardest thing, she found, “was not knowing why I was different. If you’ve got an identity that includes being black, you should be proud of it.”

Stuck in the UK

Just under half of these children were put into children’s homes. Few were adopted. Everyone involved in the adoption process appeared to assume that black or mixed-race children were “too hard to place”, an attitude that carried on into at least the 1960s. Of the 45 “brown babies” I spoke to, 21 were put into children’s homes but only four were adopted by nonrelatives. Several were adopted by their grandparents, while a few were fostered.

Leon Lomax is the only British “brown baby” I have found who was adopted by his US father. In December 1945, Somerset County Council, who had 45 mixed-race GI babies in their care, approached the Home Office to see if they could get the children adopted by “putative fathers, near relatives or other ‘colored’ families in the US” (“putative” as there was no DNA testing to establish paternity until the 1960s). But the Home Secretary pointed out that it went against the Adoption Act, which only allowed adoption by British subjects or relatives.

In 1948, the government changed its policy for just over a year (the year of Leon’s adoption), but in 1949 reverted back to the ban, despite hundreds of African Americans keen to adopt the children. It appears that in 1948 the government had become increasingly concerned that they were being seen to be shirking responsibility and of dumping the mixed-race children of British subjects onto the Americans. The Home Office explicitly wanted “to avoid any suggestion that we in this country are trying to get rid of the colored waifs left behind by the American occupation”.

Yet government’s ambivalence towards the “brown babies” remained. The children were not white and therefore not truly “British,” since Britishness assumed whiteness. In addition, a mixed-race GI baby stood out as a visual marker of the black soldier having indeed, as the comedian Tommy Trinder was well-known for quipping, been “over-paid, over-fed, over-sexed and over here.”

Finding fathers

Whether or not they grew up in a children’s home, nearly all my interviewees knew little or nothing about their fathers. They often did not even know their father’s name.

Over the years, some have found their fathers — such is the wonder of DNA testing and its increasing use in the US. Many are still finding US relatives, although it is rare that a father is still alive. For Sandi, finding her father’s wife and hearing that her father always talked of her was a turning point:

I was like tumbleweed. You know — when you see them cowboy films and the tumbleweed’s just blowing about where the wind takes it. I was like that. And I was aware of it, but I didn’t how to change it. And it’s about roots. It’s your roots that stabilise you.

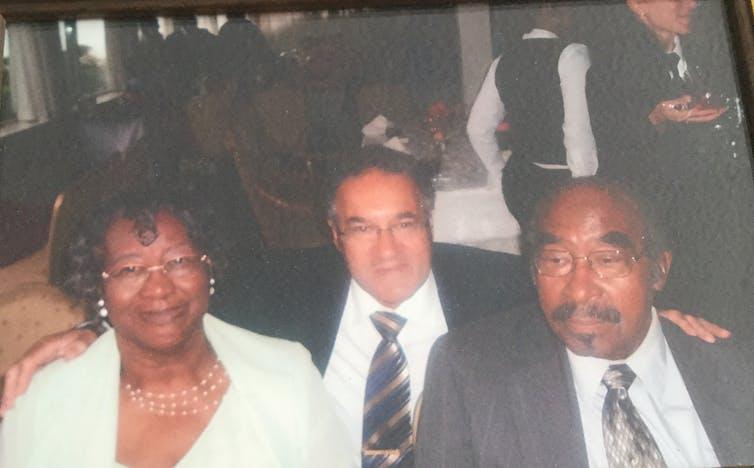

And when James met his father in 2000, he told me he felt transformed: “Up to that point, I never felt whole. There was a part of me missing. And finding my dad was that part. I felt better and settled.”

The historian David Olusoga refers to the “Windrush myth:” “The widespread misconception that black history began with the coming on that one ship.” The children left behind by the African American GIs during and after the war are part of this pre-Windrush black British history – a part that has very largely been overlooked. In generously sharing their stories, the children left behind by the African American GIs during and after the war have shone a light on an important but overlooked aspect of this pre-Windrush black British history.![]()

Lucy Bland is a professor of social and cultural history at Anglia Ruskin University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.