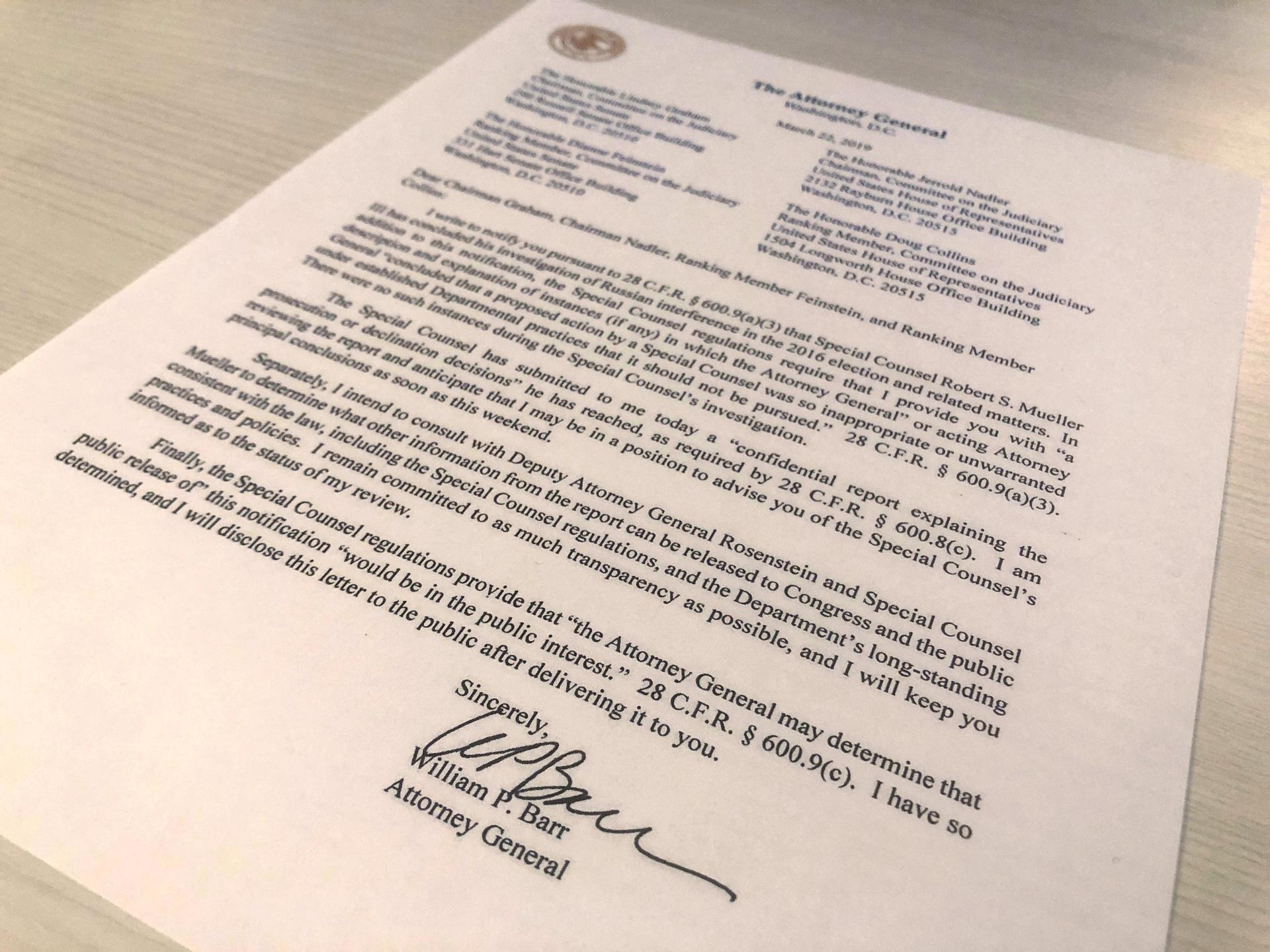

US Attorney General William Barr’s letter to lawmakers announcing the submission of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report is seen in Washington, DC.

The long-anticipated report from special counsel Robert Mueller is expected to be released on Thursday. It’s hoped that it will shed light on Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election and President Donald Trump’s efforts to obstruct federal inquiries into the matter. Attorney General William Barr, who read the report last month, said in a memo that the yearslong investigation “did not establish that members of the Trump campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.” But many have remained skeptical of this conclusion.

The full report is expected to be made public with many redactions.

The World’s host Marco Werman spoke with Tom Blanton, director of the nongovernmental, nonprofit National Security Archive at George Washington University about what redactions might be made, based on what’s been censored in past document releases.

Marco Werman: With a report like this, I’m assuming the classification has to be pretty high. Who actually inserted the black boxes? Would that be Barr himself? And do you know if, these days, this is done by hand, or is there an app for that?

Tom Blanton: There’s multiple apps. It’s done on computers these days. They actually highlight text or words or sentences that they think are still sensitive and they zap them. They have to, under the Freedom of Information Act, put out to the side what exactly they’re citing and what exemptions are made.

Related: Nixon thought he’d be the only one to ever hear his secret recordings.

Do you know of cases where two censors disagreed? What happens then?

On the wall at the National Security Archive office down at George Washington University, we have a piece of White House email that was sent to Colin Powell when he worked in the White House. The two versions are almost mirror images in the sense that the top and bottom of one version are blacked out. The middle of the second version was blacked out. The top and bottom were released, and they were declassified 10 days apart. The punchline: it was the same reviewer both times. I called him up. His name was on the document. “What were you thinking?” I asked. And he says, “Well there was probably something in the Washington Post that was sensitive about Libya the first week, so I had to cut that paragraph out. But the next week it wasn’t Libya, it was the Saudis or something, so I had to cut that paragraph out.” You get completely opposite views. My point is just that so much of the secrecy really is subjective. There’s so many sources and methods of intelligence that are so well-known in the world today that they’re not real secrets. But the government’s point of view is that it makes a difference if we acknowledge it. Therefore, you can have it on the front page of The New York Times, but that doesn’t mean we can’t still black it out when we want.

So, with the Mueller report, what would have happened if there had been disagreement about what to include and what not?

My bet is that the attorney general would not have had the folks in the room who would disagree with him. There’s a self-selection process among groups of censors. What we’ve found over two decades of fighting on the subject of secrecy is that the key to getting the most open version of a document is having multiple pairs of eyes from multiple bureaucratic locations take a look at it. There is an appeals panel that is made up of multiple agencies, and they overrule the original agency saying something was secret. They overrule them 70 to 75% of the time. That’s what I mean about it being so subjective.

What about the rules or standards for redactions that we’re using today — have they been in place for a long time?

They change from administration to administration. The standards we have now on national security have been in place since Obama did an executive order, and his order overturned an earlier order that George W. Bush had done and dramatically opened up a lot of the national security world. On the standards for withholding informant material and law enforcement material, those have really been developed by the courts over many years. There’s multiple court decisions that lay out pretty rigorous procedures for what can be protected. I think the FBI has even won a court case saying that an informant’s name from 70 years ago could still be censored from a document today because the plaintiffs couldn’t prove the person was dead. There wasn’t an obituary or death notice, and if you can’t prove they were dead, then they are still protected and they still get redacted.

Related: No, the president can’t destroy records. Here’s why.

If the standards change in future administrations, is it possible that years down the line some of these redacted passages in the Mueller report could be revealed to the general public?

Absolutely. It’s like peeling an onion. We’ve gotten copies of high-level documents over the years through Freedom of Information cases where, when the first version comes out, half of it’s withheld. Try again a few years later with a different administration, you get another chunk of it released. Gradually, over time, I think the entire text will come out and when people are doing the anniversaries, decades down the road, they are more likely to have a complete copy the Mueller report than we’re going to get.

Do you think most of these documents deserve to be classified in the first place, though?

A lot of them do, in the first place. The big argument is over how long they stay secret and how long they stay in the vault. That’s the big argument, I think, even with the redactions in the Mueller report. How really secret are they, and how long are they going to have to stay secret? Pretty much everybody, even in the security business, will say that most classified documents can be released within five, ten or 15 years. Only if it’s something like a design of a weapons system that would empower some thug in some foreign country to create danger for American citizens, then I think they have a basis for classifying that. Same thing with some brave Iranian who walks into our embassy and wants to give us the lowdown on the Ayatollah succession, but asks for anonymity. You probably want to protect that person’s identity for as long as there’s some danger to them. There are some real secrets, and that’s where I differ from people like [Julien] Assange and even Chelsea Manning, who just kind of wanted to throw it all up against the wall: “Nothing should be secret.” I disagree. Things that would really hurt people should be secrets. Things that are bottom lines in a diplomatic negotiation, probably until that negotiation is done, that can be a real secret. But most of the classified universe does not deserve to stay secret more than a couple of years.

We should point out that sloppy redactions have created a lot of problems, right? I think of the ability to lift up the black bars if you don’t know what you’re doing putting in the black bars in the first place.

I think that’s Attorney General Barr’s worst nightmare. A couple of years back, the Justice Department, under duress of a lawsuit, had to release this internal consultant’s report. People that heard about it on the outside, it exposed racism problems and discrimination problems within the Justice Department. The office at Justice redacted it using a computer program putting black blotches on. It comes out in the public and somebody realizes, “Oh, that’s just an Adobe Acrobat. I can peel that off.” And they peeled off the black. What was under there was all this embarrassing stuff about Justice Department employees complaining to their supervisors and never getting any justice out of it. That’s their worst nightmare. At the Central Intelligence Agency today, they print out the document with the black blotches and then rescan the hard copy to send it to us electronically. You can see they’re worried about that.

Many people will cry foul given the redactions in the Mueller report. Will there be lawsuits challenging some of the blacked-out sections?

I think there already are lawsuits. There are a number of Freedom of Information cases that are already in court and those plaintiffs have some tools at their disposal. Judges have the right to look at a redacted document in camera as they say in their chambers and that judge can decide for him or herself if that redaction was justified or not. A lot of times, judges don’t directly overturn a government decision, they just order the government to do another review and then when you do another review a lot of times you get a different result. The judges do have the power to push back dramatically, the judge just has to have a backbone.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.