Becoming Portuguese: How Brexit and 500 years of Jewish history changed one British’s singer’s life

Ana Silvera sings at the Manchester Jewish Museum, a former synagogue founded by a committee which included her ancestors. Since 2016, she has been applying for Portuguese citizenship under Portugal’s citizenship law for Sephardic Jewish people.

Ana Silvera was in Denmark at her partner’s parents’ house when the results of the Brexit referendum were announced. The news hit her and the whole family hard.

“I was absolutely gutted when it happened,” she said. “And no one really knows what’s going to happen — that’s the scary thing about it.”

The final impact of Brexit is still unclear for people living in the UK, but it is already having an effect on the lives of people like Ana: British citizens who work or live in EU countries.

Under EU law, every European citizen has the right to live and work in any other European country without restrictions. There are no work permits, visas or green cards inside the EU if you hold an EU passport.

For British citizens, Brexit is likely to spell the end of those privileges.

For some British people who want to remain in Europe, however, there is another possibility. Since the referendum, thousands of UK passport holders have applied for citizenship elsewhere in the EU, enabling them to bypass Brexit. In the year after the referendum, applications to do so rose by a factor of six, to more than 13,000, according to the BBC.

One of those people is Ana. Since the referendum, she has been engaged in the complex process of becoming European all over again — this time as a citizen of Portugal.

I have known Ana since we were both kids growing up in London. She is now a composer and singer-songwriter (a great one, have a listen) and lives and works part of the year in Denmark — an EU state — with her Danish partner, Jasper Høiby. Being able to travel freely between the UK and Europe is essential for her personal life and her work.

Ana’s decision to try and claim a new, EU nationality is not just practical, though. Being European is about who she is as a person.

“Probably like a lot of people who wanted to stay in Europe, I feel less welcome [in Britain] now,” she said. “It’s really strange. Suddenly, you feel an alienation.”

“For me, what made England so great was all the amazing people that I met from all over the world in England. And suddenly, they’re not welcome in Britain any more. And I find that really, really depressing.”

Ana has never lived in Portugal and has no intention of moving there if she is granted citizenship — although she does plan to visit. The application process does not require her to enter Portugal at any point: All communication can be done remotely by email and letter. When she receives emails in Portuguese about her application, she uses Google Translate to read them.

But Ana’s plan to become Portuguese is sincere and deeply felt. And she may well succeed as a result of a set of recent citizenship laws passed in Portugal and Spain. Ana first heard about them through word-of-mouth.

“I remember my auntie saying, ‘Oh, you know, you can claim Portuguese citizenship.’ At the time I was like, “Oh, that’s so nice.” But, of course, I thought it was completely irrelevant to me.”

Under Portugal’s Organic Law No. 1/2013, citizenship is available to any person who can show they are part of the Sephardic Jewish community — people descended from the community of Jews who were persecuted in Spain and Portugal during the Inquisition.

From the late 15th century onwards, Jews and Muslims were the subject of a brutal campaign of persecution across the Iberian peninsula. Decades of forced conversions, expulsions and pogroms followed.

In the Lisbon Massacre of 1506, thousands of Jews and conversos, or converted Jews, were murdered in the streets. And Ana’s surname, Silvera, is one of the Jewish family names listed in records of the time.

The first step to citizenship is to be confirmed as a genuine member of the Sephardic community by a synagogue in Lisbon or Oporto, using evidence of ancestry through surname, family language, genealogy or family memory.

Gathering this evidence dislodged more than a simple family tree for Ana. When we met in London in the summer of 2017, she arrived with piles of yellowing birth certificates, sepia photos and printed-out databases of Silvera ancestors through the centuries. (There is even more information online, where members of the Silvera clan have been reconstructing a shared history back to the Inquisition.)

As we sifted through the papers, the broad outlines of the last 500 years became clear: a very European story of migration, persecution and shifting national identity.

The Silveras fled first from Spain to Portugal, then were forced out of Portugal and settled in Italy. Like many other Sephardic families, they later moved to the Arab world, modern Syria. In the 19th century, Ana’s grandfather’s grandfather, Eli, took his family to Manchester, England.

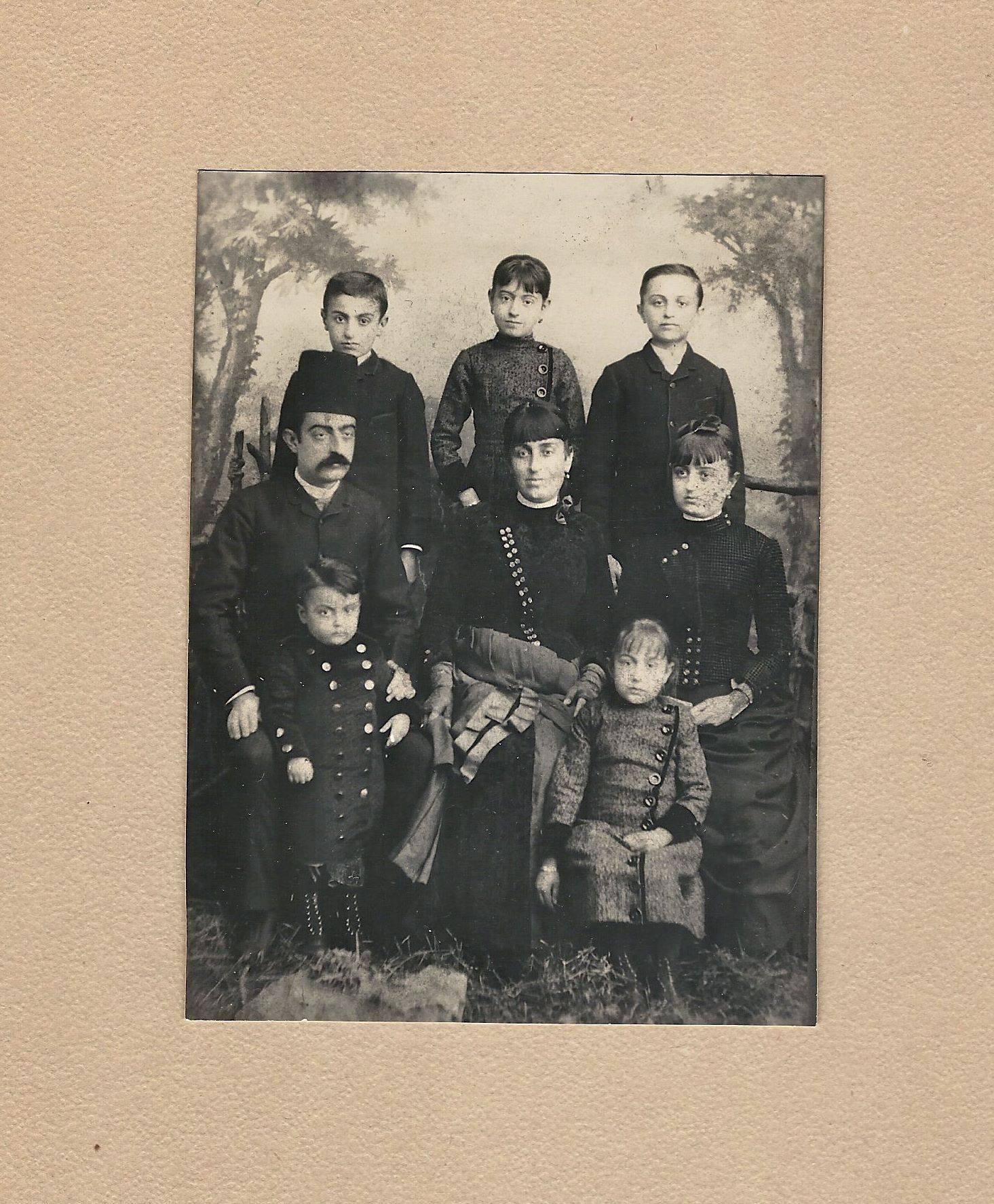

There was even a photo of the Silveras from a few years before the move to Britain: a stiffly posed, Victorian group portrait at a photography studio in Aleppo, Syria. Eli, thickly moustached, stares stoically off into the middle distance, his fez tipping at a slight angle. The women appear severe and proud or maybe just exhausted by the long exposure time. And Ana’s grandmother’s father, David, at 5 years old, stands at the front.

It seems impossibly remote, but this 19th-century world echoed through to Ana’s childhood in Britain. Her grandmother imparted a few words of Arabic on, although not the most polite phrases.

“I remember my grandma teaching me in Arabic how to say ‘son of a dog,’” Ana laughed. “And my mum was really angry that she taught me that. But my grandmother was so outrageous. Thanks Granny!”

Not all of the family moved to England; some went to Italy instead. Ana found photos of this branch of the family during her search for evidence to send to Portugal.

“They are fairly distant relatives, but they’re on this family tree,” she said. “Bahia Silvera and her daughter Violetta and Lelio Silvera.”

There were more black-and-white photos — like one of a good-looking, elegantly dressed family on a beach in the ’30s. Dad is posed by a deck chair. The kids have just come in from a swim; you can see the water still in their hair.

Ana says she was surprised by how modern these images still are. “They look so like a normal, loving, happy family — like a family today, except for some of the clothes,” she said. “And they probably stayed in Italy and felt, you know, why should we move? It’s fine. We’ve lived here all our lives. And the next thing they knew, they were on a train to Auschwitz.”

“That’s how extraordinary these everyday pictures are. It makes you remember that there are so many people who are refugees right now, just because of where they are born. This long history of people moving from country to country and claiming new nationalities.”

When we meet, there had been one piece of good news from Portugal. A few days before, the synagogue authorities wrote to say that they had considered the evidence and would issue a certificate officially confirming Ana’s membership of the Sephardic community — she passed.

In theory, the process since then should have been simple. According to a spokesperson from the Oporto synagogue, most applicants who reach this stage go on to be issued a passport by the government in Lisbon. But months, and then more than a year, went by without news of a passport.

When I contacted the synagogue in Oporto, they said that the Sephardic citizenship system has seen a huge number of applications from people all over the world, desperate for EU citizenship. And especially from British people like Ana.

At the time of this story’s airing, Ana was still waiting to see if she would be allowed to claim — or reclaim — the Portuguese citizenship that was taken from her ancestors. Denmark has introduced legislation that would temporarily protect the rights of British people already resident in the country, but it is not clear how long this protection will last. In Britain, the slow-motion political crisis of Brexit is continuing.

When I spoke to Ana recently on the phone from Copenhagen, she seemed more resigned than ever.

“The fresh shock [of Brexit] has given way to a feeling of, ‘How can I best cope with the situation?” she said. “What can I do to make sure I keep my sense of myself as a European citizen with these historical links to Portugal and Spain? [And] how do I keep my freedom of movement?”

“I guess I still think it is sad. It’s really sad, and I’ve slightly lost the hope of it changing or being reversed.”

Ana Silvera’s album “Oracles” is available on her website. Tour dates and future releases can be found on her Twitter feed.