Cracking up or cracking down? For Saudi comedians, the red lines are a ‘moving target.’

Hatoon Kadi is one of very few female comedians in Saudi Arabia.

Hatoon Kadi is one of few Saudi women who has managed to make a name for herself in comedy. Women are rarely seen onstage in the conservative kingdom, but she has a platform of her own: She hosts a popular YouTube comedy show called “Noon al-Niswa.” Some of her episodes have garnered more than 1 million views.

Kadi describes her comedy as social satire that focuses on women’s issues. Last summer, when the driving ban for women was lifted, she joked that it actually worked in favor of Saudi men.

Related: Saudi Arabia isn’t known for fun. It has a $64 billion plan to turn it around.

“So, when the ban was lifted, I said, ‘Look, now the Saudi man can gain back his original position as being the most important man in his woman’s life.’”

“It was that the most important man in a Saudi woman’s life is the driver,” she said recently from her home in Jeddah. “So, when the ban was lifted, I said, ‘Look, now the Saudi man can gain back his original position as being the most important man in his woman’s life.’ So, at the end of the day, this decision was in favor of men. Not for women,” she said with a giggle.

Related: Saudi cyclist says it takes a ‘brave heart’ to normalize the sport for women

Kadi is among a rising number of Saudi women taking to YouTube to express themselves, be it through comedy, makeup tutorials, cooking segments or lifestyle advice. Although women’s place in comedy is still strained, the kingdom is looking to capitalize on the larger cultural scene.

Last year, Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman al-Saud allowed theaters in the kingdom for the first time in decades. There are now comedy clubs, concerts and plans to build an opera house. The government has promised to invest $64 billion in the entertainment sector in the next decade.

Stand-up comedy, and public entertainment, in general, has always been very limited in Saudi Arabia, says Hala al-Dosari, a scholar at New York University. When she was growing up, “There was no public event, no entertainment,” she said. “Most of the Saudis, including my own family, would travel outside Saudi Arabia to spend their holidays or vacations. My family would go to Egypt all the time in order to have a more relaxed social atmosphere.”

Related: This Saudi tour guide wants you to come to his hometown, Jeddah

Things began to shift in the early 2000s with the introduction of the internet. YouTube became a popular platform for comedians to share their material with a wider audience.

But even then, it was unthinkable that one day, the kingdom would open up to not only comedy clubs but also to cinemas, concerts and public entertainment.

“Aside from a handful of Saudi YouTube comedy stars, performers are largely struggling without theaters and entertainment companies, as well as a lack of mass awareness of the art form,” a 2017 Arab News report says.

Tapping into youth

In Jeddah, a cosmopolitan port city along the Red Sea, some of that development is already underway. On a typical January evening, the Al Comedy Club is buzzing with people. Men and women sit together, which was unheard of not so long ago. On this particular night, the comedians, all-male, tend to stick to a few themes: marriage, family and friendship. And their wisecracks are landing — the crowd responds with enthusiasm.

Dosari, from NYU, has a couple of theories about what’s prompting the changes now. First, the idea is “to promote Mohammed Bin Salman as the visionary modernist leader and acquire the legitimacy from the international business community, international political circles,” she said. Secondly, she says, it’s about economics.

Issam Abu Suleiman, the regional director for Gulf countries at the World Bank, agrees. He says about half of the Saudi population is under 25 years old. “So, when you look down the road a little bit, you’re going to see that over the next few years, the Saudis will have to have created another 6 million jobs,” he said.

Related: Saudi women can drive. But gender equality isn’t yet ‘mainstream.’

Developing the entertainment industry has created much-needed employment for young Saudis. It’s part of the crown prince’s Vision 2030 plan, his blueprint for the next decade. Getting women behind the wheel, and into the workforce, and opening up nontraditional jobs are all part of the longer-range plan to shift the kingdom away from oil.

A ‘home’ online

Kadi says she’s had to claw her way into the comedy scene. Early on, she was convinced that mainstream media wouldn’t accept her as she is. “When you enter their doors, they will just look at you up and down and they tell you what you need to do. If you are exceptionally talented then, OK, you need to lose 10 pounds, you need to do a nose job, you need to do some Botox — even in the Arab media.”

Kadi is happy that she found a home for her comedy online. She says she still gets hateful messages via social media (lots of “synonyms for fat”), but she has learned to ignore them and instead focus on her fans, who are mostly women.

“They say, ‘You speak for us. Please never stop because we feel that you are our sister, you are our mother.’”

“They are very supportive,” she said. “They say, ‘You speak for us. Please never stop because we feel that you are our sister, you are our mother.’”

As a comedian working in a conservative society, Kadi has set herself some boundaries.

“Racism, of course. Religion, of course. Sexual references. And profanity. I just stay clear from them.”

That said, the red lines in Saudi Arabia are not so clear-cut, says Dosari. “The lines between what is allowed and what is not allowed is a moving target,” she explained. “So, it’s very difficult to follow any kind of comedy show and of course, understandably, not all of them have continued because of the restrictions.”

Fahad al-Butairi, known as the Jerry Seinfeld of Saudi Arabia, is one of the kingdom’s first professional stand-up comedians. He started out when he was a student at the University of Texas, Austin.

By 2008, he was a star in the YouTube comedy scene in Saudi Arabia. His videos got millions of views. “Haha. Wait, what?” was the title of a TedTalk he gave in 2011. “It’s also the No. 1 response when I tell anybody I am a Saudi stand-up comedian,” he said then.

When The World interviewed Butairi in 2015, he said he tries to stay clear of the kingdom’s red lines and that he had never been questioned or called in by the authorities.

But these days, Butairi is nowhere to be found. In October, The New York Times reported that he’d been arrested while working in Jordan in March and “handcuffed, blindfolded and put onto a plane for Saudi Arabia.”

This news was disturbing to those like Kirk Rudell, a writer and producer in Los Angeles who met Butairi a few years ago, when Butairi was on a trip there. Rudell was on a hunt for an Arabic speaker for the animated show, “American Dad,” and suggested him to audition.

“I did a little dive into his YouTube videos and his Twitter,” Rudell recalled. “And [he had] millions of social media followers and seemed funny and likable. Quite honestly, for the size of the role that was required, he was wildly overqualified.”

Butairi got the part, played the role and left. The two stayed in touch, and from time to time, Rudell messaged Butairi on Twitter. But when he tried last January to connect, there was a problem. Butairi’s Twitter account had been deactivated.

“That already was shocking to see,” Rudell said. “He had, I think, about 3 million followers and they were just gone. And any trace of my messages with him was gone.”

Rudell found out that Butairi’s wife, Loujain al-Hathlool, a women’s rights activist, had also been arrested. She’s still in jail, and human rights groups believe Hathlool has been tortured.

And Butairi? Rudell says nobody he knows has heard from him. Rudell decided to write a Twitter thread about the couple.

“I am a terrible fundraiser,” he told The World, recently. “I don’t like marching, but I can tell stories. And so the only thing I felt I could do for them, at least, was tell their story and try to share it and hope that whatever they were going through right now, they’d be less alone.”

A long way to go

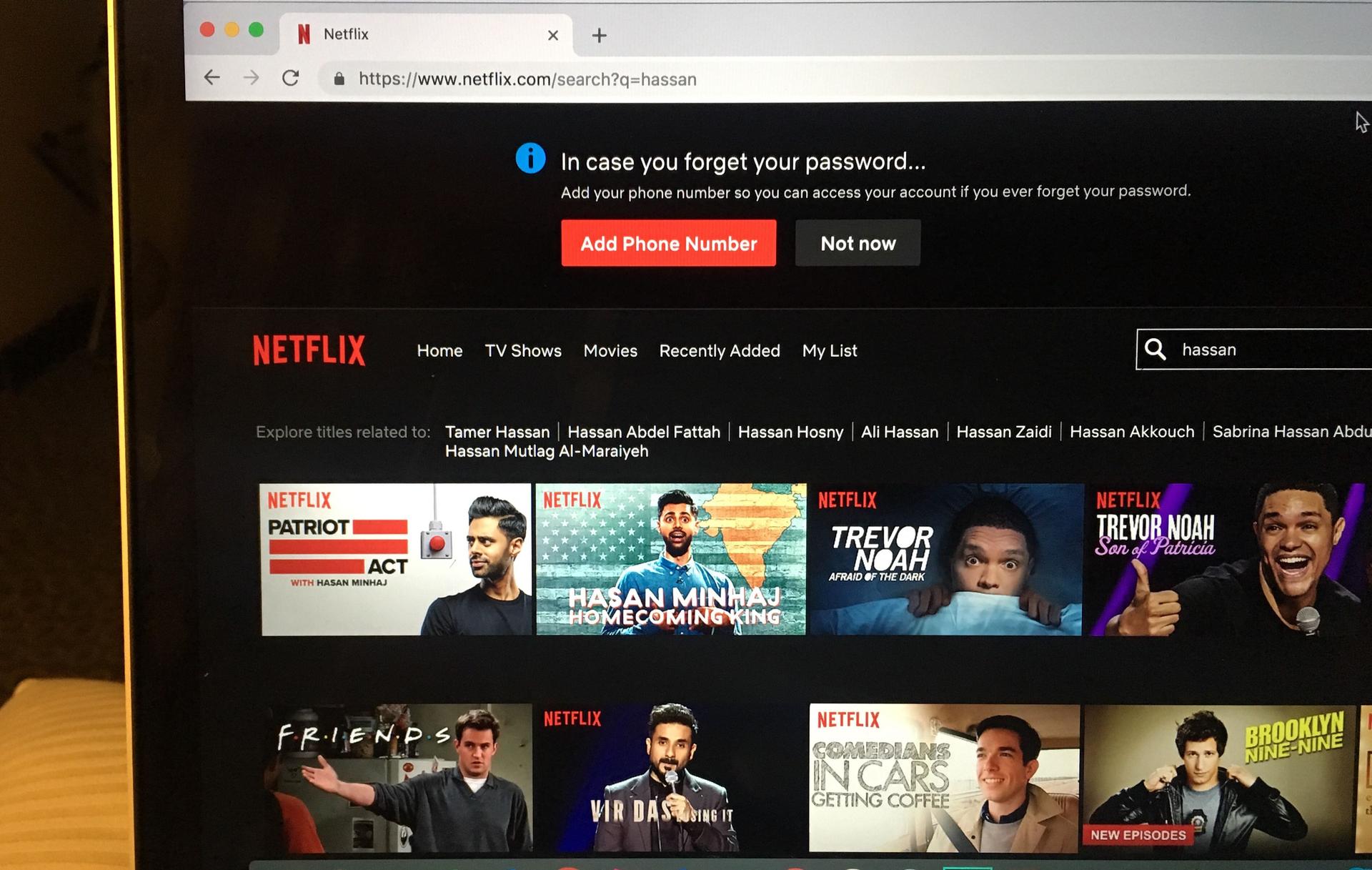

In January, Netflix raised a lot of eyebrows when it pulled an episode of “Patriot Act” by comedian Hasan Minhaj. He had taken a jab at the crown prince and Saudi Arabia’s human rights abuses.

Dosari says this shows that Saudi Arabia might have eased restrictions on entertainment, but it has a long way to go.

She says putting limits on what an artist can create takes away the purpose of the art altogether. “You can have entertainment, you can have people performing, but where is the creativity? Where is the relevance of art to everyday life? Art does not shape or influence social behavior. Art is not an agent of change.”

Instead, she says, in Saudi Arabia, art is reduced to a tool for consumerism.

Meanwhile, at 11 on a weekday morning, throngs of people line up for movie tickets at Vox Cinemas in Riyadh. The movies playing today: “Simmba,” an Indian title, “How To Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World” and “Mary Poppins,” starring Emily Blunt.

A young couple armed with popcorn says this is the first time they’ve been able to take in a film in Saudi Arabia. Although public movie theaters were allowed to open for the first time last year, every time the couple tried to go to see a film, tickets were sold out.

“Today, we got lucky that they had tickets,” the man said, adding, “We are so happy.”